Leonardo's union of art, science, and design demonstrates the thinking needed to create sustainable societies.

When it comes to connecting art, science, and design, there can be no better inspiration than Leonardo da Vinci.

He was the great genius of the Renaissance, who not only connected

these three disciplines but fused them into a seamless whole in a unique

synthesis that has not been equaled before, nor afterwards. I have

studied Leonardo's synthesis for many years. I published a book, The Science of Leonardo,

in 2007; and I have now written about three quarters of a second book,

in which I go deeper into the various branches of his science.

Most authors who have discussed Leonardo's scientific work have

looked at it through Newtonian lenses. This has often prevented them

from understanding its essential nature, which is that of a science of

organic forms, of qualities, that is radically different from the

mechanistic science of Galileo, Descartes, and Newton. And this is

precisely why Leonardo's science is so relevant today, especially for

education, as we are trying to see the world as an integrated whole,

making a perceptual shift from the parts to the whole, objects to

relationships, quantities to qualities.

The Empirical Method

In Western intellectual history, the Renaissance marks the period of

transition from the Middle Ages to the modern world. In the 1460s, when

the young Leonardo received his training as painter, sculptor, and

engineer in Florence, the worldview of his contemporaries was still

entangled in medieval thinking.

Science in the modern sense, as a systematic empirical method for

gaining knowledge about the natural world, did not exist. Knowledge

about natural phenomena had been handed down by Aristotle and other

philosophers of antiquity, and was fused with Christian doctrine by the

Scholastic theologians who presented it as the officially authorized

creed and condemned scientific experiments as subversive. Leonardo da

Vinci broke with this tradition:

"First I shall do some experiments before I proceed farther,

because my intention is to cite experience first and then with reasoning

show why such experience is bound to operate in such a way. And this is

the true rule by which those who speculate about the effects of nature

must proceed."

One hundred years before Galileo and Bacon, Leonardo single-handedly

developed a new empirical approach, involving the systematic observation

of nature, reasoning, and mathematics — in other words, the main

characteristics of what is known today as the scientific method.

Leonardo's approach to scientific knowledge was visual; it was the

approach of a painter. "Painting," he declares, "embraces within itself

all the forms of nature." I believe that this statement is the key to

understanding Leonardo's science. He asserts repeatedly that painting

involves the study of natural forms, and he emphasizes the intimate

connection between the artistic representation of those forms and the

intellectual understanding of their intrinsic nature and underlying

principles. For example, we read in a collection of his notes on

painting, known as the "Treatise on Painting":

"[Painting] with philosophic and subtle speculation considers all

the qualities of forms…. Truly this is science, the legitimate daughter

of nature, because painting is born of nature."

Nature as a whole was alive for Leonardo, and he saw the patterns and

processes in the microcosm as being similar to those in the macrocosm.

In particular, he frequently drew analogies between human anatomy and

the structure of the Earth, as in the following beautiful passage:

"We may say that the Earth has a vital force of growth, and that

its flesh is the soil; its bones are the successive strata of the rocks

which form the mountains; its cartilage is the porous rock, its blood

the veins of the waters. The lake of blood that lies around the heart is

the ocean. Its breathing is the increase and decrease of the blood in

the pulses, just as in the Earth it is the ebb and flow of the sea."

Systemic Thinker

Leonardo was what we would call, in today's scientific parlance, a

systemic thinker. Understanding a phenomenon, for him, meant connecting

it with other phenomena through a similarity of patterns. When he

studied the proportions of the human body, he compared them to the

proportions of buildings in Renaissance architecture; his investigations

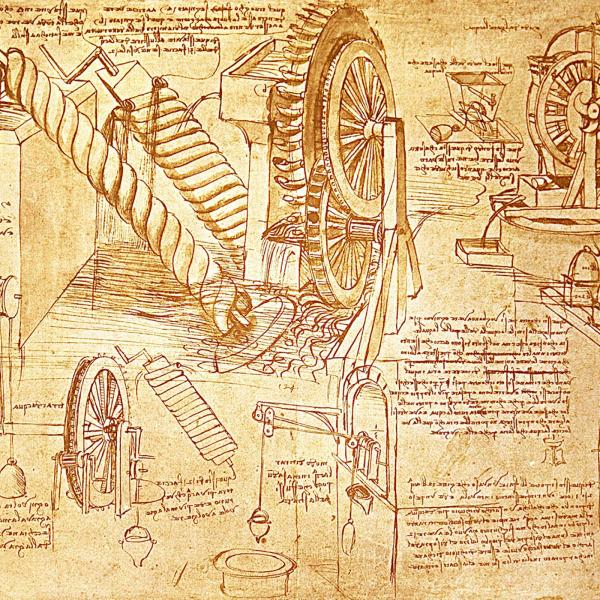

of muscles and bones led him to study and draw gears and levers, thus

interlinking animal physiology and engineering; patterns of turbulence

in water led him to observe similar patterns in the flow of air; and

from there he went on to explore the nature of sound, the theory of

music, and the design of musical instruments.

This exceptional ability to interconnect observations and ideas from

different disciplines lies at the very heart of Leonardo's approach to

learning and research, and this is something that is very much needed

today, as the problems of our world become ever more interconnected and

can only be understood and solved if we learn how to think systemically —

in terms of relationships, patterns, and context.

While Leonardo's manuscripts gathered dust in ancient European

libraries, Galileo was celebrated as the "father of modern science." One

cannot help but wonder how Western scientific thought might have

developed had Leonardo's notebooks been known and widely studied soon

after his death.

Leonardo's Legacy

Leonardo did not pursue science and engineering to dominate nature,

as Francis Bacon would advocate a century later. He abhorred violence

and had a special compassion for animals. He was a vegetarian because he

did not want to cause animals pain by killing them for food. He would

buy caged birds in the marketplace and set them free, and would observe

their flight not only with a sharp observational eye but also with great

empathy.

Instead of trying to dominate nature, Leonardo's intent was to learn

from her as much as possible. He was in awe of the beauty he saw in the

complexity of natural forms, patterns, and processes, and aware that

nature's ingenuity was far superior to human design. "Though human

ingenuity in various inventions uses different instruments for the same

end," he declared, "it will never discover an invention more beautiful,

easier, or more economical than nature's, because in her inventions

nothing is wanting and nothing is superfluous."

This attitude of seeing nature as a model and mentor is now being

rediscovered in the practices of ecological design and biomimicry. Like

Leonardo, ecodesigners today study the patterns and flows in the natural

world and try to incorporate the underlying principles into their

design processes. This attitude of appreciation and respect of nature is

based on a philosophical stance that does not view humans as standing

apart from the rest of the living world but rather as being

fundamentally embedded in, and dependent upon, the entire community of

life in the biosphere.

Today, this philosophical stance is promoted by the school of thought

known as "deep ecology." Shallow ecology views humans as above or

outside the natural world, as the source of all value, and ascribes only

instrumental, or "use," value to nature. Deep ecology, by contrast,

does not separate humans — or anything else — from the natural

environment. It sees the living world as being fundamentally

interconnected and interdependent and recognizes the intrinsic value of

all living beings. Amazingly, Leonardo's notebooks contain an explicit

articulation of that view:

"The virtues of grasses, stones, and trees do not exist because

humans know them.… Grasses are noble in themselves without the aid of

human languages or letters."

In view of this deep ecological awareness and of Leonardo's systemic

way of thinking, it is not surprising that he spoke with great disdain

of the so-called "abbreviators," the reductionists of his time:

"The abbreviators do harm to knowledge and to love.... Of what

use is he who, in order to abridge the part of the things of which he

professes to give complete knowledge, leaves out the greater part of the

things of which the whole is composed?… Oh human stupidity!... Don't

you see that you fall into the same error as he who strips a tree of its

adornment of branches laden with leaves, intermingled with fragrant

flowers or fruit, in order to demonstrate the suitability of the tree

for making planks?"

This statement is not only revealing testimony of Leonardo's way of

thinking, but is also ominously prophetic. Reducing the beauty of life

to mechanical parts and valuing trees only for making planks is an

eerily accurate characterization of the mindset that dominates our world

today. This, in my view, is the main reason why Leonardo's legacy is

immensely relevant to our time.

As we recognize that our sciences and technologies have become

increasingly narrow in their focus, unable to understand our

multi-faceted problems from an interdisciplinary perspective, and

dominated by corporations more interested in financial rewards than in

the well-being of humanity, we urgently need a science that honors and

respects the unity of all life, recognizes the fundamental

interdependence of all natural phenomena, and reconnects us with the

living Earth. What we need today is exactly the kind of science Leonardo

da Vinci anticipated and outlined 500 years ago.

This essay is adapted from lectures delivered by Fritjof Capra at

the Center for Ecoliteracy's seminar "Sustainability Education:

Connecting Art, Science, and Design," August 16–18, 2010.

New Lessons from Leonardo

In

order to reconnect to the natural world today, Fritjof Capra suggests

we need to embrace the same elements Leonardo outlined 500 years ago.

This essay is adapted from a talk in which Fritjof Capra discusses some of the findings described in his latest book, Learning from Leonardo: Decoding the Notebooks of a Genius (2013: Berrett-Koehler Publishers).

Leonardo da Vinci, the great genius of the Renaissance, developed and

practiced a unique synthesis of art, science, and technology, which is

not only extremely interesting in its conception but also very relevant

to our time.

As we recognize that our sciences and technologies have become

increasingly narrow in their focus, unable to understand our

multi-faceted problems from an interdisciplinary perspective, we

urgently need a science and technology that honor and respect the unity

of all life, recognize the fundamental interdependence of all natural

phenomena, and reconnect us with the living Earth. What we need today is

exactly the kind of synthesis Leonardo outlined 500 years ago.

A science of living forms

At the core of Leonardo's synthesis lies his life-long quest for

understanding the nature of the living forms of nature. He asserts

repeatedly that painting involves the study of natural forms, of

qualities, and he emphasizes the intimate connection between the

artistic representation of those forms and the intellectual

understanding of their intrinsic nature and underlying principles. In

order to paint nature's living forms, Leonardo felt that he needed a

scientific understanding of their intrinsic nature and underlying

principles, and in order to analyze the forms of nature, he needed the

artistic ability to draw them. His science cannot be understood without

his art, nor his art without the science.

The quest for the secret of life

I have been fascinated by the genius of Leonardo Lea Vinci and have

spent the last ten years studying his scientific writings in facsimile

editions of his famous notebooks. In my new book, I present an in-depth

discussion of the main branches of Leonardo's scientific work — his

fluid dynamics, geology, botany, mechanics, science of flight, and

anatomy. Most of his astonishing discoveries and achievements in these

fields are virtually unknown to the general public.

What emerged from my explorations of all the branches of Leonardo's

science was the realization that, at the most fundamental level,

Leonardo always sought to understand the nature of life. My main thesis

is that the science of Leonardo da Vinci is a science of living forms,

radically different from the mechanistic science of Galileo, Descartes,

and Newton that emerged 200 years later.

This has often escaped earlier commentators, because until recently

the nature of life was defined by biologists only in terms of cells and

molecules, to which Leonardo, living two centuries before the invention

of the microscope, had no access. But today, a new systemic

understanding of life is emerging at the forefront of science — an

understanding in terms of metabolic processes and their patterns of

organization; and those are precisely the phenomena which Leonardo

explored throughout his life, both in the macrocosm of the Earth and in

the microcosm of the human body.

In the macrocosm, the main themes of Leonardo's science were the

movements of water, the geological forms and transformations of the

Earth, and the botanical diversity and growth patterns of plants. In the

microcosm, his main focus was on the human body — its beauty and

proportions, the mechanics of its movements, and the understanding of

the nature and origin of life. Let me give you a very brief summary of

his achievements in these diverse scientific fields.

The movements of water

Leonardo was fascinated by water in all its manifestations. He

recognized its fundamental role as life's medium and vital fluid, as the

matrix of all organic forms: "It is the expansion and humor of all

living bodies," he wrote. "Without it nothing retains its original

form." This view of the essential role of water in biological life is

fully borne out by modern science. Today we know not only that all

living organisms need water for transporting nutrients to their tissues,

but also that life on Earth began in water, and that for billions of

years, all the cells that compose living organisms have continued to

flourish and evolve in watery environments. So, Leonardo was completely

correct in viewing water as the carrier and matrix of life.

Throughout his life, Leonardo studied its movements and flows, drew

and analyzed its waves and vortices. He experimented not only with water

but also investigated the flows of blood, wine, oil, and even those of

sand and grains. He was the first to formulate the basic principles of

flow, and he recognized that they are the same for all fluids. These

observations establish Leonardo da Vinci as a pioneer in the discipline

known today as fluid dynamics.

Leonardo's manuscripts are full of exquisite drawings of spiraling

vortices and other patterns of turbulence in water and air, which until

now have never been analyzed in detail, because the physics of turbulent

flows is notoriously difficult. In this book, I present an in-depth

analysis of Leonardo's drawings of turbulent flows, based on extensive

discussions with Ugo Piomelli, professor of fluid dynamics at Queen's

University in Canada, who very generously helped me to analyze all of

Leonardo's drawings and descriptions of turbulent flows.

The living Earth

Leonardo saw water as the chief agent in the formation of the Earth's

surface. This awareness of the continual interaction of water and rocks

impelled him to undertake extensive studies in geology, which informed

the fantastic rock formations that appear so often in the shadowy

backgrounds of his paintings. His geological observations are stunning

not only by their great accuracy, but also because they led him to

formulate general principles that were rediscovered only centuries later

and are still used by geologists today.

Leonardo was the first to postulate that the forms of the Earth are

the result of slow processes taking place over long epochs of what we

now call geological time.

With this view, Leonardo was centuries ahead of his time. Geologists

became aware of the great duration of geological time only in the early

19th century with the work of Charles Lyell, who is often considered the

father of modern geology.

Leonardo was also the first to identify folds of rock strata. His

descriptions of how rocks are formed over enormously long periods of

time in layers of sedimentation and are subsequently shaped and folded

by powerful geological forces come close to an evolutionary perspective.

He arrived at this perspective 300 years before Charles Darwin, who

also found inspiration for evolutionary thought in geology.

The growth of plants

Leonardo's notebooks contain numerous drawings of trees and flowering

plants, many of them masterpieces of detailed botanical imagery. These

drawings were at first made as studies for paintings, but soon turned

into genuine scientific inquiries about the patterns of metabolism and

growth that underlie all botanical forms. Leonardo paid special

attention to the nourishment of plants by sunlight and water, and to the

transport of the sap through the plants' tissues.

He correctly distinguished between the dead outer layer of a tree's

bark and the living inner bark, known to botanists as the phloem, which

he called very aptly "the shirt that lies between the bark and the

wood." He was also the first to recognize that the age of a tree

corresponds to the number of rings in the cross-section of its trunk,

and — even more remarkably — that the width of a growth ring is an

indication of the climate during the corresponding year. As in so many

other fields, Leonardo carried his botanical thinking far beyond that of

his peers, establishing himself as the first great theorist in botany.

The human body in motion

Whenever Leonardo explored the forms of nature in the macrocosm, he

also looked for similarities of patterns and processes in the human

body. In order to study the body's organic forms, he dissected numerous

corpses of humans and animals, and examined their bones, joints,

muscles, and nerves, drawing them with an accuracy and clarity never

seen before. Leonardo demonstrated in countless elaborate and stunning

drawings how nerves, muscles, tendons and bones work together to move

the body.

Unlike Descartes, Leonardo never thought of the body as a machine,

even though he was a brilliant engineer who designed countless machines

and mechanical devices. He clearly recognized that the anatomies of

animals and humans involve mechanical functions. "Nature cannot give

movement to animals without mechanical instruments," he explained, but

that did not imply for him that living organisms were machines. It only

implied that, in order to understand the movements of the animal body,

he needed to explore the principles of mechanics. Indeed, he saw this as

the most "noble" role of this branch of science.

Elements of mechanics

To understand in detail how nature's "mechanical instruments" work

together to move the body, Leonardo immersed himself in prolonged

studies of problems involving weights, forces, and movements — the

branches of mechanics known today as statics, dynamics, and kinematics.

While he studied the elementary principles of mechanics in relation to

the movements of the human body, he also applied them to the design of

numerous new machines, and as his fascination with the science of

mechanics grew, he explored ever more complex topics, anticipating

abstract principles that were centuries ahead of his time.

These include his understanding of the relativity of motion, his

discovery of the principle now known as Newton's third law of motion,

his intuitive grasp of the conservation of energy, and — perhaps most

remarkably — his anticipation of the law of energy dissipation, the

second law of thermodynamics. Although there are many books on

Leonardo's mechanical engineering, there is as yet none on his

theoretical mechanics. In the longest chapter of this book, I provide an

in-depth analysis of this important branch of Leonardo's science.

The science of flight

From the texts that accompany Leonardo's anatomical drawings we know

that he considered the human body as an animal body, as biologists do

today; and thus it is not surprising that he compared human movements

with the movements of various animals. What fascinated him more than any

other animal movement was the flight of birds. It was the inspiration

for one of the great passions in his life — the dream of flying.

The dream of flying like a bird is as old as humanity itself. But

nobody pursued it with more intensity, perseverance, and commitment to

meticulous research than Leonardo da Vinci. His science of flight

involved numerous disciplines — from aerodynamics to human anatomy, the

anatomy of birds, and mechanical engineering.

In my chapter on Leonardo's science of flight, I analyze his drawings

and writings on this subject in some detail, and I come to the

conclusion that he had a clear understanding of the origin of

aerodynamic lift, that he fully understood the essential features of

both soaring and flapping flight, and that he was the first to recognize

the principle of the wind tunnel — that a body moving through

stationary air is equivalent to air flowing over a stationary body. This

establishes Leonardo da Vinci as one of the great pioneers of

aerodynamics.

In his numerous designs of flying machines, Leonardo attempted to

imitate the complex flapping and gliding movements of birds. Many of

these designs were based on sound aerodynamic principles, and it was

only the weight of the materials available in the Renaissance that

prevented him from building viable models.

The mystery of life

As I have mentioned, the grand unifying theme of Leonardo's

explorations of the macro- and microcosm was his persistent quest to

understand the nature of life. This quest reached its climax in the

anatomical studies he carried out in Milan and Rome when he was over

sixty, especially in his investigations of the heart — the bodily organ

that has served as the foremost symbol of human existence and emotional

life throughout the ages. He not only understood and pictured the heart

in ways no one had before him; he also observed subtleties in its

actions that would elude medical researchers for centuries.

During the last decade of his life, Leonardo became intensely

interested in another aspect of the mystery of life — its origin in the

processes of reproduction and embryonic development. In his

embryological studies, he described the life processes of the fetus in

the womb, including its nourishment through the umbilical cord, in

astonishing detail. Leonardo's embryological drawings are graceful and

touching revelations of the mysteries surrounding the origins of life.

Leonardo knew very well that, ultimately, the nature and origin of

life would remain a mystery, no matter how brilliant his scientific

mind. "Nature is full of infinite causes that have never occurred in

experience," he declared in his late forties, and as he got older, his

sense of mystery deepened. Nearly all the figures in his last paintings

have that smile that expresses the ineffable, often combined with a

pointing finger. "Mystery to Leonardo," wrote the famous art historian

Kenneth Clark, "was a shadow, a smile, and a finger pointing into

darkness."

Links:

https://www.ecoliteracy.org/article/what-we-can-learn-leonardo

https://www.ecoliteracy.org/article/new-lessons-leonardo