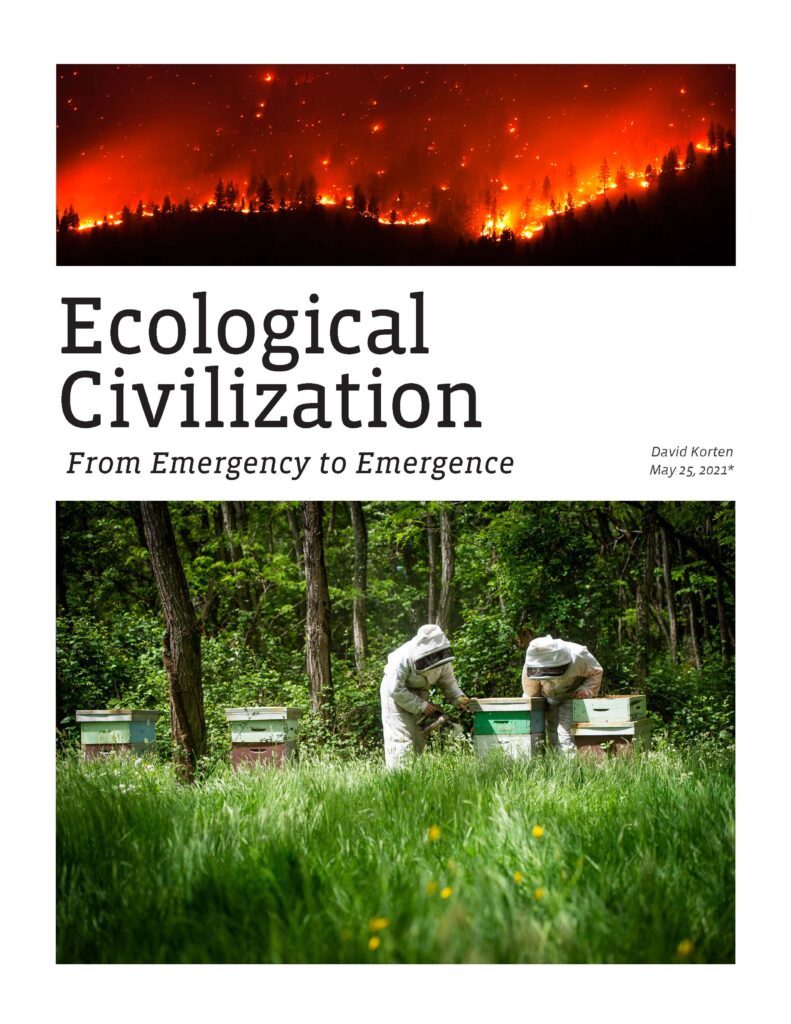

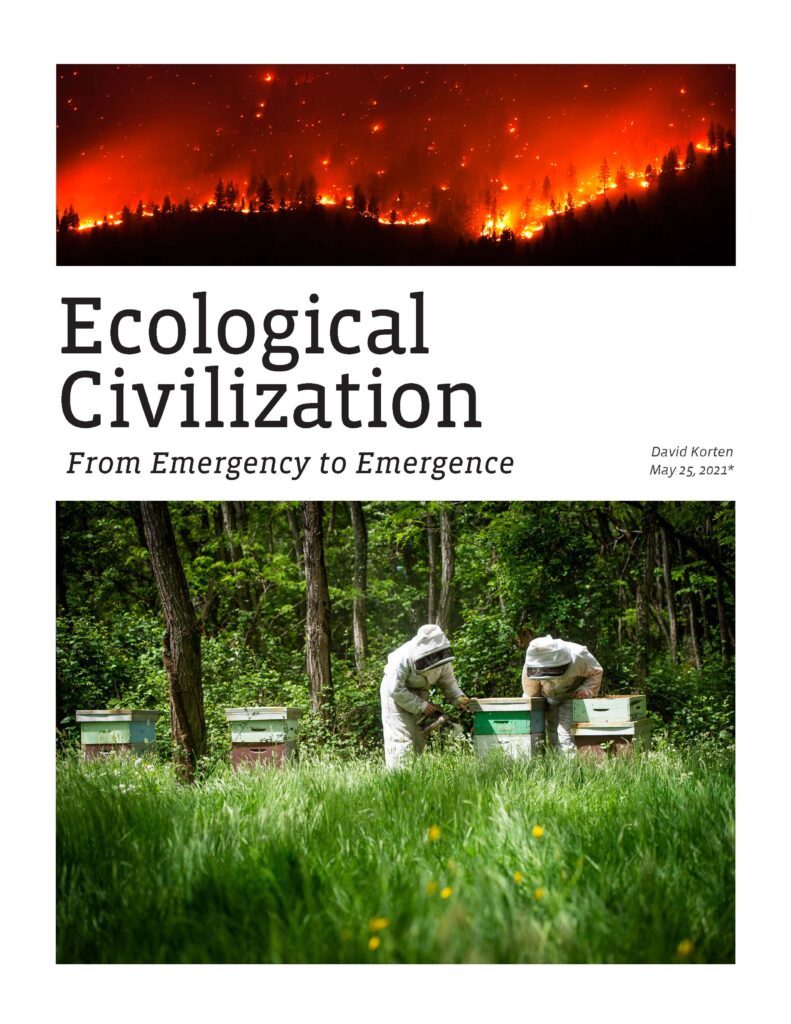

Drawing on the work and insights of many colleagues and from ongoing conversations, this paper was written in an effort to connect the dots and engage a serious conversation about the causes of the existential crisis we face, while bringing a message of hope and possibility.

Click on the image below to read the paper and download the PDF. (For the best version to read via mobile devices, click HERE.) Feel free to use this paper and its content in any way you believe may be useful in your work, community, and personal life to draw attention and help move us forward on the path to an Ecological Civilization.

– David Korten, May 25, 2021 (Updated with minor revisions on Nov 3, 2021.)

Read and download the PDF…

Read on mobile device…

See Fritjof Capra’s Reflections on Ecological Civilization: From Emergency to Emergence (video)

Link: https://davidkorten.org/ecological-civilization-from-emergency-to-emergence/

NEXT_SYSTEM-Living_Earth_System_Model

Humans are a choice making species with a common future faced with an epic choice. We can continue to seek marginal adjustments in the culture and institutions of the Imperial Civilization of violence, domination, and exploitation that put us on a path to self-extinction. Or we can transition to an Ecological Civilization dedicated to restoring the health of living Earth’s regenerative systems while securing material sufficiency and spiritual abundance for all people.

***Read David’s latest paper, Ecological Civilization: From Emergency to Emergence, in which

he connects the dots to engage a serious conversation about the causes of the existential crisis we face,

while bringing a message of hope and possibility.***

We humans now consume at a rate 1.7 times what Earth can sustain. By January 2020, the wealth of just 26 billionaires had grown to exceed that of the poorest half of humanity–3.9 billion people. That was before the Coronavirus pandemic drove breathtaking growth of the wealth gap.

Our future turns on a simple, nearly forgotten, truth. We humans are living beings born of and nurtured by a living Earth. Our health and well-being depend on her health and well-being. As she cares for us, we must also care for her.

This is a foundational premise of the emerging vision of the possibilities of an Ecological Civilization grounded in a New Enlightenment understanding of the beauty, wonder, meaning, and purpose of creation.

A Vision of Human Possibility

Adjustments at the margins of the failed cultural and institutional system of the Imperial Era will not take us where we must now go. The system’s cultural beliefs and institutional structures must be retooled and its resources reallocated to realign the defining purpose of human society from making money to supporting every person in making a living.

Hope resides in humanity’s emerging vision of an Ecological Civilization grounded in our deepest human understanding of creation’s purpose, life’s organizing principles, and our human nature and possibility as discerned by the converging insights of indigenous wisdom keepers, the great spiritual teachers, and leading-edge scientists. Some call this emerging 21st Century intellectual frame, the New or Second Enlightenment.

Naming the future, calls us to envision it. Naming it a new civilization evokes a sense of epic transformation. Identifying it as ecological evokes a New Enlightenment understanding of life as complex, intelligent, conscious, and self-organizing.

Earth Charter

The Earth Charter—the product of a broadly participatory global process begun at the 1992 Rio Earth Summit—was finalized and launched in 2000. A 2002 paper by Elizabeth Ferrero and Joe Holland suggested the Principles of the Earth Charter, be considered principles for an Ecological Civilization.

China

In 2012, China officially adopted Ecological Civilization in its Communist Party Constitution and mandated its incorporation into “all aspects of economic, political, cultural, and social progress.” China is a country of 1.3 billion people with a Communist government and the world’s 2nd largest capitalist economy. It faces extreme environmental crises. Experiencing the benefits and burdens of both capitalism and communism, its attempts to deal with its environmental crisis uniquely position it for global leadership toward a new human framework that transcends both. The Guizhou Institute of Environmental Science Research and Design is working with the Global Footprint Network to develop the metrics for an Ecological Civilization for China.

Parliament of the World’s Religions

Ecological Civilization has also been embraced by the Parliament of the World’s Religions, which in 2015 issued a consensus Declaration on Climate Change that concluded with these words:

The future we embrace will be a new ecological civilization and a world of peace, justice and sustainability, with the flourishing of the diversity of life. We will build this future as one human family within the greater Earth community.

This statement clarifies the relationship between Earth Community and Ecological Civilization. Earth Community refers to Earth’s interdependent community of life self-organizing in concert with Earth’s geological structures and processes to create and maintain the conditions essential to the existence of all Earth life. Ecological Civilization refers to the human subsystem within the meta-system of Earth’s community of life. Coincidentally the two terms share the same acronym (EC), which can be used to refer to either or both.

A working paper, “Toward an Ecological Civilization: A Path to Justice, Peace, and Care for Earth,” was prepared as background for a series of presentations on the human step to an ecological civilizations by John Cobb, Matthew Fox, David Korten, Frances Korten, and Jeremy Lent, at the 2018 Parliament of World Religions in Toronto. Read the paper HERE.

Claremont Conference

In 2015 an international conference held at Pomona College in Claremont California on the theme Seizing an Alternative — Toward an Ecological Civilization drew 1,500 leading thinkers, authors, academics, activists, theologians, philosophers, and scientists. Shortly thereafter, sponsors of the Claremont conference launched Toward Ecological Civilization (EcoCiv – aka Institute for Ecological Civilization), a think and action tank dedicated to identifying “how social, political, and economic life needs to be organized if humanity is to achieve a sustainable, ecological society over the long-term.

Grounded in a 21st Century Enlightenment

The Enlightenment of the 18th Century raised our human recognition and understanding of the role of physical mechanism, causality, and order in the universe and became the foundation of what academic philosophers call Modernism. It strengthened the authority of science, challenged traditional religious and political hierarchies, and unleashed dramatic advances in technology, democracy, and individual liberty.

This opened new human possibilities, including technological advances that with time virtually eliminated geographical barriers to human communication and exchange. It supported the spread of democracy and human liberty and medical advances that significantly increased human life expectancy and unleashed a dramatic growth in our human numbers.

Concurrently, in its denial of conscious intelligence and agency, it stripped life of meaning and absolved us individually and collectively of responsibility for the consequences of our human choices. Our new abilities supported a fragmentation and monetization of human relationships and eroded our sense of connection to family, community and living Earth.

We grew the power of our instruments of war and our ability to dominate and exploit one another and nature to support previously unprecedented levels of material extravagance by the few at the expense of the many. During the latter half of the 20th Century, our material consumption exceeded for the first time the limits of Earth’s capacity to sustain us. The institutions of democracy became subverted by global financial markets and corporations for which people and Earth were nothing more than a means to profit.

We lived an illusion of growing prosperity for all in the midst of a reality in which fewer and fewer control and consumer more of a shrinking pie of Earth’ real wealth. The disastrous consequences now threaten to drive a massive dieback, if not the extinction, of the human species.

The rapidly deepening human crisis cannot be resolved with the same mindset and institutions that created it. Hope lies in the new understanding of the now emerging New Enlightenment. Grounded in traditional understanding, the wisdom of the world’s great spiritual traditions, and dramatic breakthroughs in the findings of quantum physics and the biological and ecological sciences, the New Enlightenment recognizes conscious intelligence as the ground of all being.

Our primary sources of knowledge and understanding are converging to affirm that there is far more to what we experience as material reality than material mechanism and chance. Consciousness, intelligence, and agency are integral and pervasive.

Living Earth: A Superorganism

The wonder of organic (carbon-based) life is that every living organism, from the individual cell to living Earth, maintains itself in an internal state of active, adaptive, resilient, creative thermodynamic disequilibrium in seeming violation of the basic principle of entropy. It takes a community of organic life to create and maintain the conditions that carbon-based life requires. Earth itself exemplifies this principle.

According to evolutionary biologists the first living organisms appeared on Earth some 3.6 billion years ago. We still have little idea how it happened. We do know, however, that as their numbers, diversity, and complexity increased, they organized themselves into a planetary-scale living system comprised of trillions of trillions of individual choice-making living organisms. Together, they worked with Earth’s geological processes to filter excess carbon and a vast variety of toxins from Earth’s air, waters, and soils and sequester them deep underground—preparing the way for the emergence of more advanced species.

In a continuing process—and with no discernible source of central direction—Earth’s community of life continues to self-organize to renew Earth’s soils, rivers, aquifers, fisheries, forests, and grasslands while maintaining global climatic balance and the composition of Earth’s atmosphere .

Likewise, the human body is best understood as a self-organizing community of tens of trillions of individual, living, choice-making cells that together create and maintain the superorganism that serves as the vehicle of our agency and houses our individual consciousness. Each cell is making constant decisions that simultaneously balance its own needs and those of the larger whole on which it depends and which in turn depends on it. It all happens below the level of individual human awareness.

Science has only the sketchiest idea of how it works beyond a recognition that organic life organizes not as hierarchies of central control, but as holarchies of nested, communities that self-organize from the bottom up. We humans must now learn to do the same.

By the understanding of the New Enlightenment, we humans are living beings born of and nurtured by a living Earth, itself born of and nurtured by a living universe unfolding toward ever greater complexity, beauty, awareness, and possibility. Creation thus reveals its purpose—a quest to know itself and its possibilities through an epic journey of self-discovery thru a process of eternal learning and becoming.

This restores a sense of the purpose and meaning of life that the 18th Century Enlightenment stripped away. And it provides an essential frame for a Great Turning to a New Economy that meets the essential physical needs of all people within the regenerative capacities of a healthy, finite living Earth community of life.

An Epic Challenge and Opportunity

We humans are now a truly global species. Our common future depends on our successful transition to an Ecological Civilization that works in balanced and harmonious relationship with Earth’s living systems to provide every person with a means of living adequate to their health and happiness. Yet we remain burdened by a 5,000 year cultural and institutional legacy of an Imperial Era that divides us by nationality, religion, class, race, and gender and pits us against one another in a violent competition for wealth and power.

The challenges of the transition are summed up in a paper by Chris Williams, “How will we get to an ecological civilization?” Williams concludes that:

It will not only be a question of constructing a new society, but deconstructing the old one. It is not enough to take over and reassemble the state,…; we will need to reassemble the whole world – every single aspect of humanity’s relationship with each other and the natural world. Just like the state, an infrastructure designed to dominate nature cannot simply be appropriated and used to good ends.

Ultimately, it is vital that fighters for social emancipation, human freedom and ecological sanity recognize that capitalism represents the annihilation of nature and a functioning and diverse biosphere and, thus, human civilization. A system based on cooperation, genuine bottom-up democracy, long-term planning and production for need, not profit,… represents the reconciliation of humanity with nature.

To achieve this future, we must navigate a successful transition from:

- Transnational corporations to national governments as our primary institutions of governance,

- Competition to cooperation as our dominant mode of relating, and

- Growing GDP to meeting the spiritual and material needs of all within the limits of what living Earth can sustain as the economy’s defining purpose.

Base on the deepening understanding of the New Enlightenment, the governing institutions of an Ecological Civilization will support national and bio-regional self-reliance, the free sharing of information and technology, and balanced trade in goods for which one nation has a natural surplus and another is unable reasonably to produce for itself.

An authentic economics for an Ecological Civilization will be grounded in the scientific understanding of how living communities of trillions of individual living organisms self-organize to create and maintains the conditions essential to life’s existence. It will measure economic performance by indicators of the healthy function of individuals, families, communities, local biosystems, and Earth’s global biosphere.

Consistent with these truths, the legal principles of an Ecological Civilization will recognize that:

- Individual persons possess both rights and corresponding responsibilities.

- Governments must be accountable to the people who form them.

- Corporations are created by government to fulfill a public purpose within that government’s jurisdiction and are accountable to that government for fulfilling that purpose.

Other Resources

Sam Geall, “Interpreting Ecological Civilisation,” Part I of a three-part series.

Zhu Guangyao, “Ecological Civilization: Our Planet,” UNDP.

Zhang Chun, “China’s New Blueprint for an Ecological Civilization,” The Diplomat

Thomas Berry, “The Determining Features of the Ecozoic Era,” conference handout 2004. What Berry called the Ecozoic Era was pretty much synonymous with the concept of an Ecological Civilization.

Three Overview Presentations

David Korten, “Birthing an Ecological Civilization: Overview.” This is a short-overview introduction to the human transition to an Ecological Civilization written for a general readership.

David Korten, “A Living Earth Economy for an Ecological Civilization,” 2017 opening keynote presentation to the 20th annual International Week, hosted by the Global Education Program at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. Explores implications for the academy and institutions of higher learning.

David Korten, “A Living Earth Economy for an Ecological Civilization,” 2016 keynote address to the Donghu Forum on Global Governance in Wuhan China addresses a high level Chinese audience and makes the case that among the world’s nations, China is positioned to take the global lead on advancing an Ecological Civilization.

+254 733 632755

+254 733 632755