Tools for Systems Thinkers: The 6 Fundamental Concepts of Systems Thinking

By https://medium.com/disruptive-design

Tools for Systems Thinkers: Designing Circular Systems

Over the last five chapters in this series on tools for systems thinkers, I have looked at fundamental concepts, feedback loops, dominant archetypes and shared systems mapping tools.

I have worked on synthesizing the critical tools that assist with the

development of a more three-dimensional perspective of how the world

works. By no means have I covered it all, but I hope to have helped

ignite curiosity around the power of a systems-based perspective and the

opportunity that we all have in learning to love complex problems and

embrace challenges in more proactive ways.

In

the final chapter of this series, I cover some of the ways that

thinking in systems can transition us to a circular economy.

Specifically, I discuss how we can design circular systems that

facilitate sustainable and regenerative outcomes. For a more detailed

introduction to these concepts, take a look at the Circular Systems Design Activation Pack we created.

On Design

First

let me say that while I am a designer and advocate for professionals to

make intentional sustainability and systems based contributions through

their creative productions, when I say ‘design’ in this piece, I am

referring to design as the common practice of producing ‘things’. This

can be anything — artifacts, conversations, or policies, all of which

have impacts on the world. From supermarket designs, to government

regulations, to how we design our own lives, these are all the product

of design — the intent to direct or construct the world in a particular

way.

Design is a conscious and intuitive effort to impose meaningful order. Design is both the underlying matrix of order and the tool that creates it. — Victor Papanek

I

have written and spoken extensively on the role that design plays in

scripting out lives, influencing our minds and curating our experience

of the world (see here, here, here and here).

In

some cases ‘designs’ have massive impacts, and in others, only minor

roles. Nonetheless, everyday design is the act of creating something

new, so let’s dive into how we can design circular systems that build in

intentionally for positive impacts on people and the planet.

“You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.” ― R. Buckminster Fuller

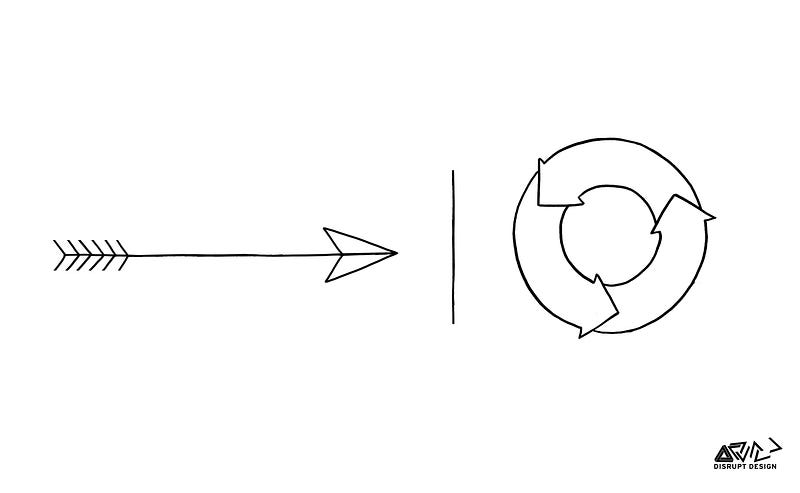

The Circular Economy

For many people the term ‘circular economy’

is still new, so allow me to briefly explain what this is all about.

Our current economy is based on a linear system of production where we

take raw materials and natural resources out of nature, process them

into usable goods to meet human needs, and then discard them back into

giant holes in the ground that, ironically, were often where we took the

raw materials from to begin with.

This

entire system is in opposition to the natural systems that sustain life

on Earth — which are circular and regenerative — and it’s

counterintuitive to the way we function as living organisms (for example

we all require nutrients to survive, which is part of the beautifully

designed system of nutrients cycling through bodies and back into the

ground to grow the next generation of food, this nutrient cycle is one

of the fundamental ecosystems that sustain life on Earth).

Basically

humans designed a broken system that creates waste and constantly loses

value through the economy. Our linear economy does not fit in a

circular world.

The

opposite to a linear system is a circular one. When you use the natural

world as a design reference, you quickly see that everything not only

plays a role, but also puts back in what it took out.

Most

organisms in nature, as well as the principles that nature plays by,

are regenerative; humans, however, design systems that are the exception

to this rule. Herein lies the problem that the circular economy

movement, and many other attempts (cleaner production, eco design, life

cycle assessment, industrial ecology etc.), that have come before, have

tried to address.

These

attempts have all worked hard to solve the complex puzzle of meeting

humanity’s growing needs while not screwing up the life support systems

that both nourish all living organisms (thank you food, air, and water)

but work effortlessly in amazingl complex ways to make life happen on

this magical ball of water and soil that we all share.

I

could go on and on about this missing link in our current economic and

social structures, the design mistakes that perpetuate it, how our

education system devalues circularity and prioritizes reductionism… But

right now I’m going to invest this time in the more interesting part,

where we figure out how to not make

a mess of this beautiful planet and instead, start to design out waste

and find unique ways of being a productive contributor to the planet (to

this end I am working on a project for a post disposable future, check it out here).

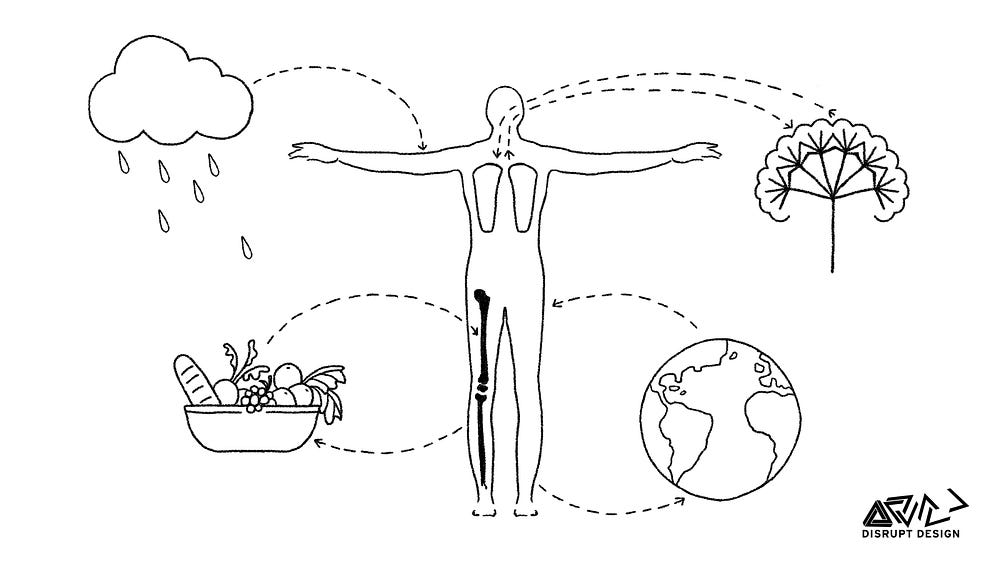

Everything is Interconnected

All

of this all boils down to the simple reality that we all have an

intuitive understanding of — everything is interconnected to everything

else in some way. Nothing living is in isolation, and we are require

other systems to survive—thus we are all in an interconnected,

interdependent relationship with everything else. I say this in a

non-hippy way, look at the design of a tree and you will see the same

fractile patterns in your lungs, your life is reinforced every few

seconds as you breath in oxygen that was produced free of charge by a

bunch of trees and phytoplankton.

We

live of a closed ecosystem that is perfectly calibrated for success.

Our bodies are small versions of this, and we benefit every second of

the day from the services that this giant ecosystem provides us.

Many

of the human-created systems that we have, such as cities, factories,

governments and industrial food production, are failed emulations of the

way nature designs things because they have not been designed as a

system that nests within other systems. They are isolated and siloed,

linear and reductive.

This

is where humans have really messed up: we have made things based on our

reductive one-dimensional perspective of the world, rather than taken

on the more detailed, systemic and creative perspective of what makes

everything work on Earth.

So

when we are seeking to solve and evolve some of the more complex

problems humanity faces, we must start first with a shift in mindset

from the one dimension of a linear plane to a three-dimensional

perspective of the interconnected and dynamic nature of systems at play

in the world around us.

This

requires not only developing systems thinking skills, but also

understanding sustainability sciences and developing reflexivity,

creativity and fostering more divergent neurological practices that

enhances creativity. These 3 things form the pillars of a practice in

creative systems change and can be applied by anyone who has invested

the energy in learning the practice tools.

We

are not born ignorant to the systems that sustain us (hang out with a

curious 5-year-old to learn all about how nature works), and we know creativity is a learned skill that

maximizes the hidden potential of the human brain. We have the building

blocks for designing a circular and regenerative future.

Circular Systems Design

Designing

for circular systems is about considering the full-picture perspective

of how the status quo of the natural, industrial, and social systems

play out, and then uncovering ways of shifting these to facilitate

circular and regenerative outcomes.

In

some cases this is extremely complicated (like how to circularize spent

nuclear rods, for example), and in others, it’s a no- brainer (like how

to change our collective addiction to disposable items like coffee

cups). But all of the systems changes we need to design have the same

basic elements: people, products, places, and processes. They can all be

redesigned to maximize benefits and minimize negative externalities.

Yes,

there is a level of complexity to this approach. But everything worth

doing requires work, and purpose-driven creatives in this world are at

the forefront of helping to activate this change from linear to circular

design. I will work on more content (additional to what I have already produced

for this new field) to help fuel this shift in the future, but for now I

encourage you to seek out resources that help you start to circularize

your thinking and doing in the world, from how you consume products

through to the decisions you make in your professional role.

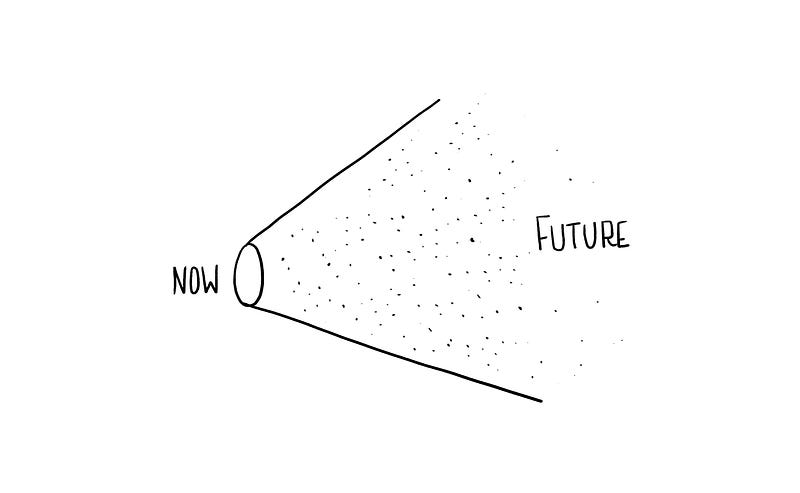

There

are many narratives of the future being all f*$cked up, but I

personally refuse to believe in a dystopian future as nothing is

actually defined about what will happen next. We are all making up the

future based on our collective individual actions today.

There

is no definite fact that robots will take over our jobs and that

presidents will push the big red button, just as there is no reason why

we can’t rapidly change the way we get the goods and services we desire

and need. I am completely confident in our capacity as a species to

figure out how to be a sustainable and regenerative contributor to the

magic that is life on Planet Earth.

— —

If this is your thing, check out my 4-week advanced training in circular systems design,

an online rapid learning journey and mentorship program for

professionals wanting to level up their skills in circular systems

design (starting in Jan 4. 2018). I offer one-on-one mentorship and

tailored content to help get you to a confident knowledge and leadership

position.

If you are not quite ready for advanced training, take my systems thinking class at the UnSchool online.

Beautiful illustrations by the talented Emma Segal

In this series on systems thinking, I share the key insights and tools needed to develop and advance a systems mindset for dealing with complex problem solving and transitioning to the Circular Economy.

I have taught thousands of hours of

workshops in systems, sustainability and design, and over the years

refined ways of rapidly engaging people with the three dimensional

mindset needed to think and work in circular systems. My motivation for

writing this online toolkit is to help expand the ability of

professionals to rapidly adopt to a systems mindset for positive impact.

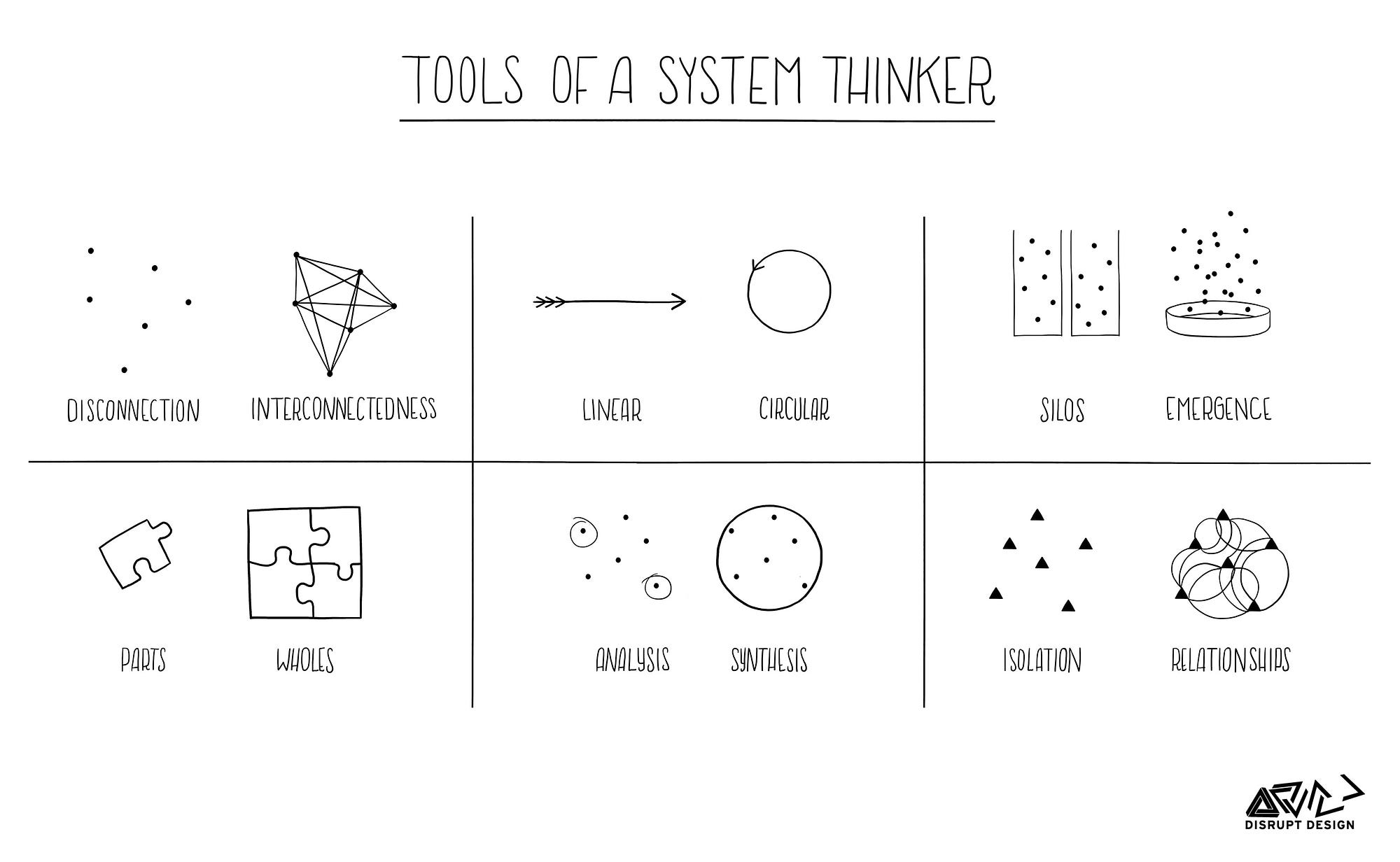

Words

have power, and in systems thinking, we use some very specific words

that intentionally define a different set of actions to mainstream

thinking. Words like ‘synthesis,’ ‘emergence,’ ‘interconnectedness,’ and

‘feedback loops’ can be overwhelming for some people. Since they have

very specific meanings in relation to systems, allow me to start off

with the exploration of six* key themes.

*There are way more than six, but I picked the most important ones that you definitely need

to know, and as we progress through this systems thinking toolkit

series, I will expand on some of the other key terms that make up a

systems mindset.

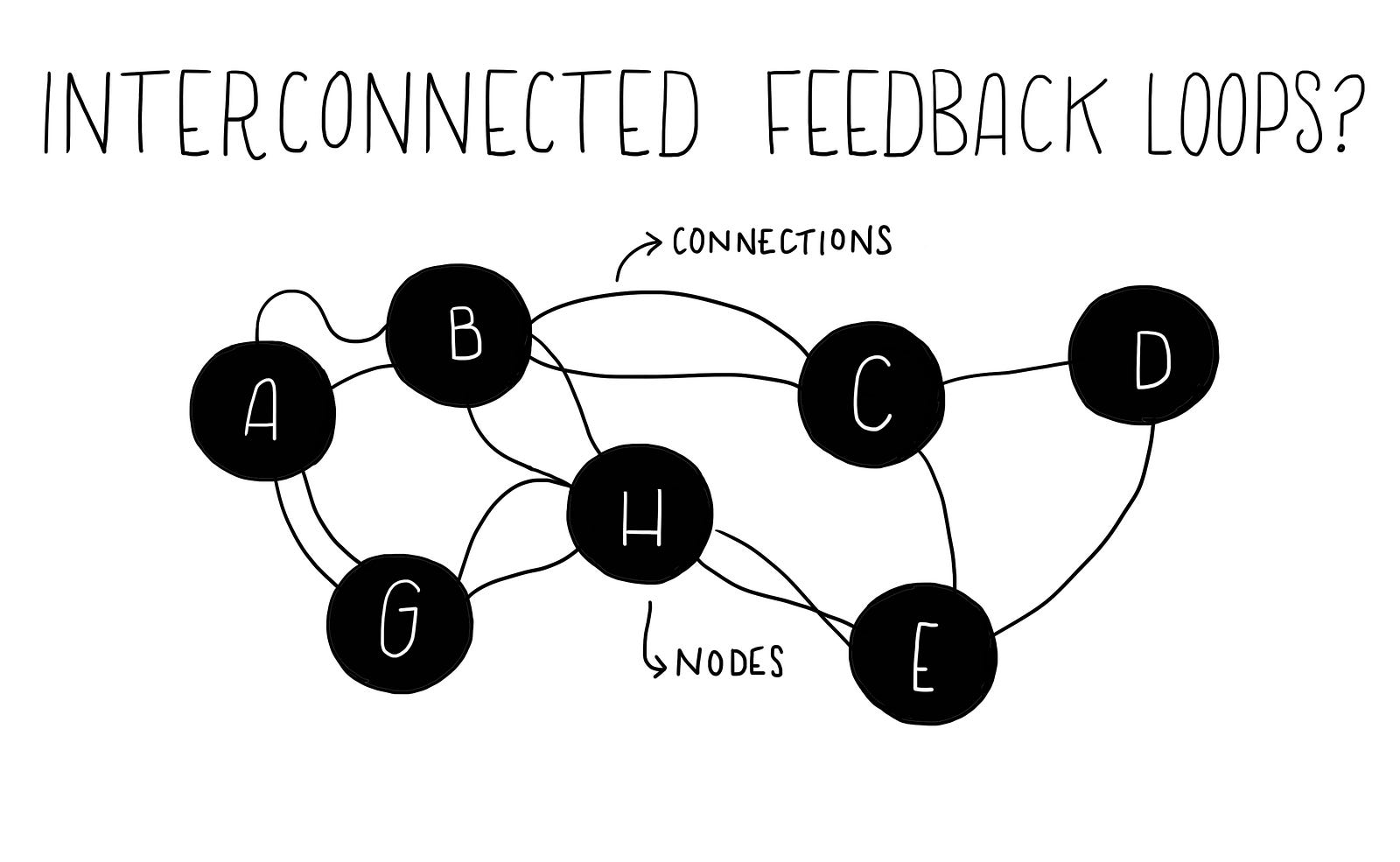

1. Interconnectedness

Systems thinking requires a shift in mindset,

away from linear to circular. The fundamental principle of this shift

is that everything is interconnected. We talk about interconnectedness

not in a spiritual way, but in a biological sciences way.

Essentially,

everything is reliant upon something else for survival. Humans need

food, air, and water to sustain our bodies, and trees need carbon

dioxide and sunlight to thrive. Everything needs something else, often a

complex array of other things, to survive.

Inanimate

objects are also reliant on other things: a chair needs a tree to grow

to provide its wood, and a cell phone needs electricity distribution to

power it. So, when we say ‘everything is interconnected’ from a systems

thinking perspective, we are defining a fundamental principle of life.

From this, we can shift the way we see the world, from a linear,

structured “mechanical worldview’ to a dynamic, chaotic, interconnected

array of relationships and feedback loops.

A systems thinker uses this mindset to untangle and work within the complexity of life on Earth.

2. Synthesis

In

general, synthesis refers to the combining of two or more things to

create something new. When it comes to systems thinking, the goal is

synthesis, as opposed to analysis, which is the dissection of complexity

into manageable components. Analysis fits into the mechanical and

reductionist worldview, where the world is broken down into parts.

But

all systems are dynamic and often complex; thus, we need a more

holistic approach to understanding phenomena. Synthesis is about

understanding the whole and the parts at the same time, along with the

relationships and the connections that make up the dynamics of the

whole.

Essentially, synthesis is the ability to see interconnectedness.

3. Emergence

From

a systems perspective, we know that larger things emerge from smaller

parts: emergence is the natural outcome of things coming together. In

the most abstract sense, emergence describes the universal concept of

how life emerges from individual biological elements in diverse and

unique ways.

Emergence

is the outcome of the synergies of the parts; it is about non-linearity

and self-organization and we often use the term ‘emergence’ to describe

the outcome of things interacting together.

A

simple example of emergence is a snowflake. It forms out of

environmental factors and biological elements. When the temperature is

right, freezing water particles form in beautiful fractal patterns

around a single molecule of matter, such as a speck of pollution, a

spore, or even dead skin cells.

Conceptually,

people often find emergence a bit tricky to get their head around, but

when you get it, your brain starts to form emergent outcomes from the

disparate and often odd things you encounter in the world.

There is nothing in a caterpillar that tells you it will be a butterfly — R. Buckminster Fuller

4. Feedback Loops

Since

everything is interconnected, there are constant feedback loops and

flows between elements of a system. We can observe, understand, and

intervene in feedback loops once we understand their type and dynamics.

The two main types of feedback loops are reinforcing and balancing. What can be confusing is a reinforcing feedback loop is not usually a good thing. This happens when elements in a system reinforce more of the same, such as population growth or algae growing exponentially in a pond. In reinforcing loops, an abundance of one element can continually refine itself, which often leads to it taking over.

A balancing feedback loop, however, is where elements within the system balance things

out. Nature basically got this down to a tee with the predator/prey

situation — but if you take out too much of one animal from an

ecosystem, the next thing you know, you have a population explosion of

another, which is the other type of feedback — reinforcing.

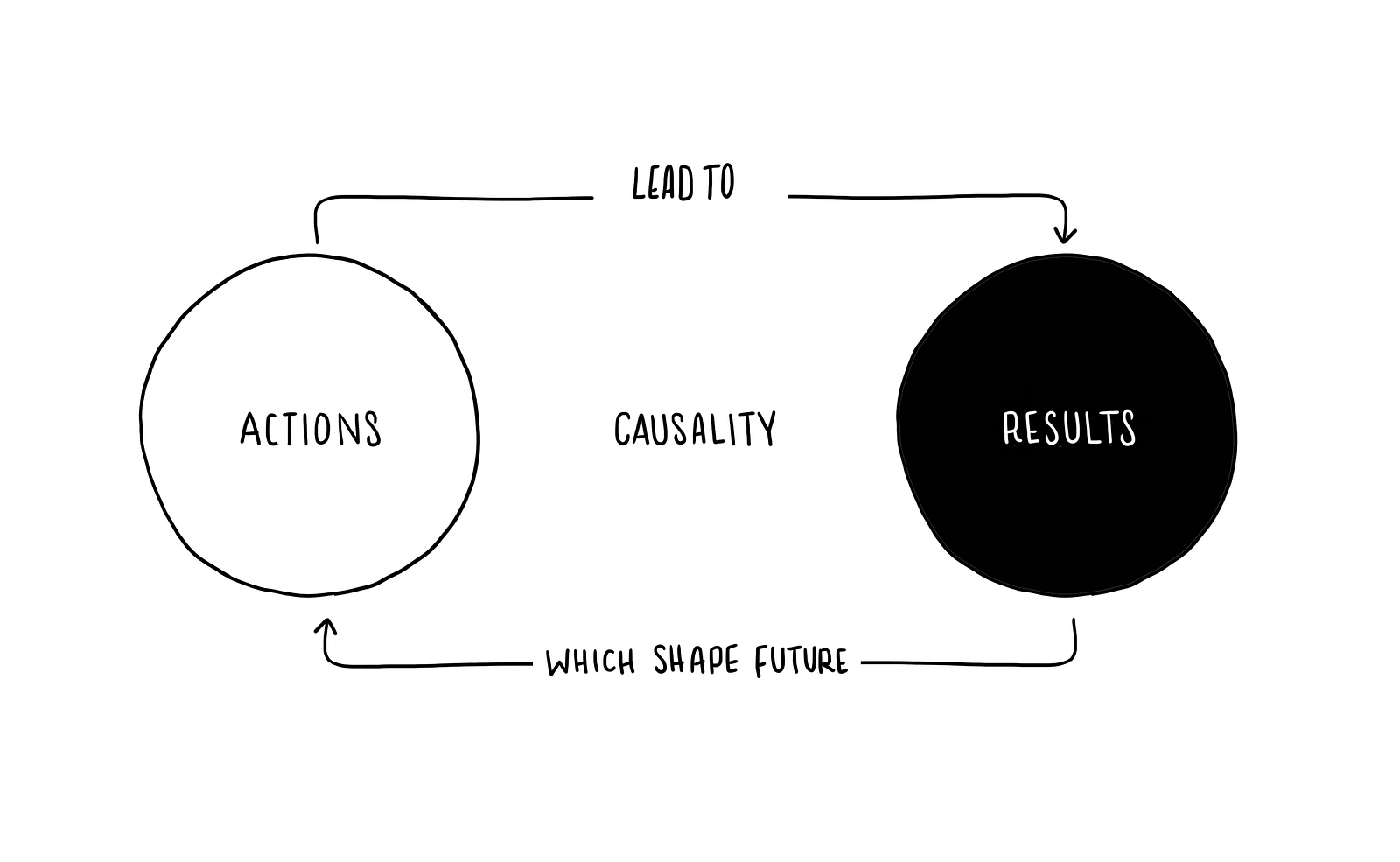

5. Causality

Understanding

feedback loops is about gaining perspective of causality: how one thing

results in another thing in a dynamic and constantly evolving system

(all systems are dynamic and constantly changing in some way; that is

the essence of life).

Cause

and effect are pretty common concepts in many professions and life in

general — parents try to teach this type of critical life lesson to

their young ones, and I’m sure you can remember a recent time you were

at the mercy of an impact from an unintentional action.

Causality

as a concept in systems thinking is really about being able to decipher

the way things influence each other in a system. Understanding

causality leads to a deeper perspective on agency, feedback loops,

connections and relationships, which are all fundamental parts of

systems mapping.

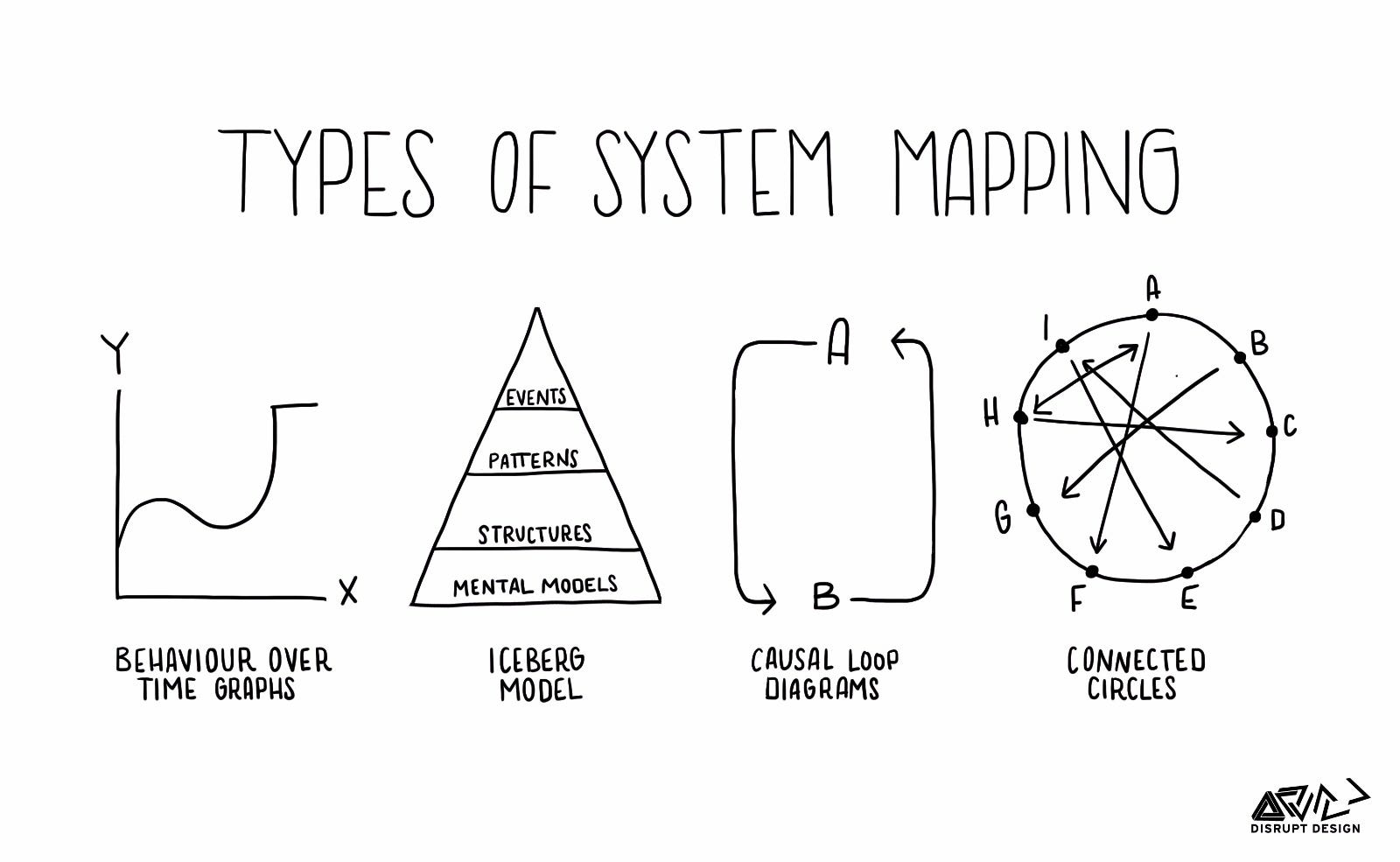

6. Systems Mapping

Systems

mapping is one of the key tools of the systems thinker. There are many

ways to map, from analog cluster mapping to complex digital feedback

analysis. However, the fundamental principles and practices of systems

mapping are universal. Identify and map the elements of ‘things’ within a

system to understand how they interconnect, relate and act in a complex

system, and from here, unique insights and discoveries can be used to

develop interventions, shifts, or policy decisions that will

dramatically change the system in the most effective way.

This

introduction to six key concepts are critical building blocks for

developing a detailed perspective of how the world works from a systems

perspective and will enhance your ability to think divergently and

creatively for a positive impact.

Working

and teaching systems thinking for years has led me to develop

additional new tools, as well as employ these time-honored concepts from

the pioneers.

What

stands out to me as critical in order to make a positive impact, is the

ability to develop your own individual agency and actions. To do that,

you first have to wrap your head around the core concepts. I have an

online class where I explain all of this here.

In the next chapter in this series, I will go into more detail on understanding systems dynamics, a core part of the practice. If you want to go even deeper, check out the full suite of programs I have created with my team at Disrupt Design and the UnSchool.

We designed them to help individuals and organizations level up their

change making abilities for a positive, regenerative, and circular

economy.

— — — — — -

All the beautiful illustrations are by Emma Segal and for the inspiration sources that helped develop these please see www.leylaacaroglu.com/credits

- Everything is interconnected: We live on a closed ecosystem called planet Earth where everything is connected to everything else. Otherwise, it ceases to survive and thrive.

- The easy way out often leads back in: If the solution were easy then it should have already been found.

- Today’s problems are yesterday's solutions: We need to make sure we don't accidentally create tomorrow problems through today's solutions.

- There is no blame in complex systems: Everything is interconnected. Thus, it's impossible to ever find one culprit for a problem. Systems have both the issue and the solution embedded within.

- Parts are elements of a complex whole: Everything is part of something else; there are no isolated elements in a complex system.

- There are no simple solutions to complex problems: We need to embrace complexity in order to truly address complex issues. Otherwise, we just deflect the problem to somewhere else in the system.

- Small, well-placed interventions can have big impacts: A well-designed, small intervention can result in significant and enduring systems change if it is in the right place – this is called a leverage point.

- Humans make linear systems – nature makes circular ones: We can learn to create regenerative products and services through understanding nature's design principles.

- Time changes complexity: Over time, things naturally get more complex. Simplicity and efficiency are very different things, yet we always think we can oversimplify complexity or reduce it down to the sum of its parts.

- ‘Failure’ is discovery in disguise: If there is no blame, then there is always an opportunity to discover through failure.

- Cause and effect are not related in time nor space: There is a mismatch and often a delay in the relationship between the cause of a problem in complex systems and the result (or symptom) appearing obvious.

Link: https://medium.com/disruptive-design/tools-for-systems-thinkers-the-6-fundamental-concepts-of-systems-thinking-379cdac3dc6a

https://www.disruptdesign.co/articles?category=Systems%20Thinking

Q Design Pack Systems Thinking | 21st CENTURY EDUCATION . http://educators.brainpop.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/IOP_QDesignPack_SystemsThinking_1.0.pdf