[Note: This presentation was developed for the Colorado Agriculture "Big and Small" Conference in Brighton, Colorado, on Feb. 26, 2010]

Ethanol plant, Yuma CO

I’m a journalist and communicator at heart, and I started working for the local newspaper in Yuma when I was in the sixth grade. I watched the landscape and the town change with deep changes in agriculture.

For nearly the last five years I’ve been working on relocalization in Boulder County and more recently across the state, working towards our communities being able to meet their essential needs locally, and in the process to become more resilient and self-reliant.

To begin this presentation, I’m going to give the briefest possible summary I can of the situation, our potential response, and what’s possible—maybe five minutes—then back it up with some details. Then I’ll talk about the involvement of the Transition movement in food and agriculture, along with some of the things we’re working on in Boulder County. Afterwards, I hope we can discuss all this together for a little while.

I’m probably going to step on a few landmines here, maybe break some taboos. But I ask for your patience.

Here’s my quick, thumbnail sketch of the situation, the highly condensed version:

Because the way we eat and the way we grow our food is a major contributor to climate change and global warming…

Because industrial food production is so energy-intensive and so dependent on oil for fertilizer, pesticides, planting and harvesting, processing, packaging, and transportation…

Because global oil production likely peaked in July 2008, which means that energy will be increasingly expensive in the future…

Because the age of cheap fossil fuels has come to an end…

Because the economy has been based on an abundant supply of cheap fossil fuels…

Because therefore food prices will soon increase dramatically, and food shortages will begin to happen—even here—perhaps in the next couple of years…

Because the U.S. is becoming a net food importer…

Because humanity is now consuming more food than we are producing…

Because industrial agriculture—like the globalized economy—is at a crossroads and is about to go into an unexpected decline…

Because much of the food that industrial agriculture produces is destroying our national’s health …

Because the way we grow much of our food is destroying and washing away our precious topsoil…

Because we can no longer conscionably support a food system that causes hunger, starvation, and disease in other parts of the world…

Because the way we eat is destroying our connection with the earth, with the natural processes and cycles of earth and sky, with those who grow our food, with the essence of life…

Because the way we eat has seriously weakened our communities…

Because maybe less than one percent of our current diet is local…

Because in Colorado we spend more than ten billion dollars on food each year, almost all of which is fleeing outside the state, lost to our local economies…

And because we know all this…

We must learn everything we can about our food predicament. We must all learn to grow at least some of our own food. We must all support the revitalization of local agriculture. We must end our dependence on fossil fuels, chemical fertilizers, and mechanization in our food production. We must commit to healing and rebuilding the soil everywhere we can. We must dramatically increase local food production for local consumption.

We must rebuild the local food infrastructure for processing and distribution. We must stop supporting and consuming non-local food. We must support local farmers, local producers, local grocers, and local restaurants.

We must learn how to eat seasonally. We must learn how to preserve and store food. We must plan how we’re going to build food security in our communities, and plan how we’re going to feed our people when things get tough. We must be prepared to share what we have to eat.

We must develop new skills and knowledge—composting, vermiculture, permaculture, soil-building, seed-saving, cultivating, canning and preserving, cooking, nutrition planning, herbal medicine.

We must make our foodshed as local as possible.

And we must do all this rather quickly.

If all this sounds like hard work, well, it is! But what would happen if we did this?

Our health would improve greatly, especially the health of our children. We’d feel more connected, more alive, more engaged, living more meaningful and more satisfying lives. We’d be devoted to rebuilding the soil in our farmlands. Our local farmers would be able to buy the land on which they farm. We’d transform the landscape. Our agricultural land would mostly be used for food production for local consumption. We’d produce thousands of new jobs; our local economies would be robust! We’d dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions and environmental degradation. We’d be sequestering carbon in the soil, in plant growth. We’d have plans and food stores in place to feed all our people in times of crisis or emergency. We’d all have a far greater degree of food security and food sovereignty; major corporations would no longer be in control of what and how we eat. Our foodshed would be resilient and self-reliant.

This would be a revolution!

The Food and Farming Predicament

Okay, now let me back up and go into a little more depth.We face a daunting predicament with the way we’re producing and consuming our food. We could frame the heart of our predicament around a key concept that we’re all learning about these days: sustainability. Now, mostly we’ve been forced into learning about sustainability because modern industrial agriculture has some real problems here, and these have kind of crept up on us. We didn’t see all this coming, but here’s some of what we’ve been discovering (of course, most of you already know these things; I’m just trying to put it into some kind of context):

First, industrial agriculture is having serious and unexpected environmental impacts: fertilizer runoff has created dead zones in our oceans; the search for more arable land has devastated our forests; irrigation methods have depleted surface and ground water; the way we farm is eroding our topsoil and reducing soil fertility; pesticides and herbicides have polluted our air and water; monocropping has resulted in loss of habitat for many species.

And agriculture has become a major contributor to climate change. If we consider the manufacture and use of pesticides and fertilizers; fuel and oil for tractors, equipment, trucking and shipping; electricity for lighting, cooling, and heating; and emissions of carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide and other green house gases—the total impact of farming and food production may be between 25 and 30 percent of the U.S.’s collective carbon footprint.

If we add to this the carbon sequestration that is lost every year through deforestation to increase land for agricultural use, the total contribution of industrial agriculture to climate change is simply enormous.

At the same time, it seems that much of the food we have been producing has actually been decreasing in quality. Food is too cheap! We spend only 10% of our income to feed ourselves; we don’t value food enough. We’ve seen an epidemic of obesity and malnutrition (in Boulder County, 49% of our residents are overweight or obese), along with a dramatic increase in chronic food-related diseases and food-borne illnesses.

These impacts are serious enough, but may not even be the most significant impacts of industrial agriculture. We’ve also witnessed the loss of the web of connections at the heart of our society. Our towns and cities do not function as communities any more. People are disconnected from food, from the people who grow it, and from the land. There is a profound lack of public awareness of environmental costs and health consequences of processed foods. Rural economies have been left in shambles, as agricultural outputs are shipped to distant markets. Our communities can no longer feed themselves.

These impacts are serious enough, but may not even be the most significant impacts of industrial agriculture. We’ve also witnessed the loss of the web of connections at the heart of our society. Our towns and cities do not function as communities any more. People are disconnected from food, from the people who grow it, and from the land. There is a profound lack of public awareness of environmental costs and health consequences of processed foods. Rural economies have been left in shambles, as agricultural outputs are shipped to distant markets. Our communities can no longer feed themselves.At the same time, on top of all this, there is a growing global food crisis that is symptomatic of our predicament. In the last couple of years, we’ve seen runaway inflation of food prices, growing inequities in the availability of food staples, food riots in at least 30 nations, and scientists calling for a moratorium on biofuel production.

The food crisis is also local. In 2008, we witnessed 40,000 people show up at the Miller Farm by Platteville when they opened their fields for gleaning. Hunger is on the increase even in America, and it’s extending well into the middle class. Poorer families often have to choose between food, medical care, or heat. They just can’t afford them all.

The Coming “Perfect Global Storm”

Gleaning at Miller Farm

The biggest driver is going to be the increasing cost and decreasing availability of fossil fuels, especially oil. Because agriculture is so dependent on oil, the entire system is extremely vulnerable to oil depletion—and to oil price spikes.

The situation brewing on the horizon regarding oil compels us to begin rethinking how we grow our food, and even how we eat.

The application of fossil fuels to the food system has supported a human population growing from fewer than two billion in 1990 to nearly seven billion today. In the process, the way we feed ourselves has changed profoundly.

The population is expected to grow to about nine billion by the middle of this century, and there is great concern about how we’re going to feed all those people. The system is already straining to keep up.

What’s not on the radar of most people—including governments and industry—is that our supply of cheap oil on which we all depend (most especially in agriculture) is shrinking.

We’ve likely already reached the peak of global oil production, and are facing an irreversible decline rate that will be somewhere between three and nine percent per year. We’re at the tipping point right now.

So, the bottom line is not good news: Oil is going to become increasingly scarce and increasingly expensive over time—beginning very soon. This will fundamentally change how we farm and how we eat, and the local food and farming revolution is in many ways an attempt to anticipate and prepare for what’s inevitably coming.

So, the bottom line is not good news: Oil is going to become increasingly scarce and increasingly expensive over time—beginning very soon. This will fundamentally change how we farm and how we eat, and the local food and farming revolution is in many ways an attempt to anticipate and prepare for what’s inevitably coming.Of course, it’s not just farming that’s going to be impacted, because our entire globalized economy is based on an abundant supply of fossil fuels, especially oil. The economic downturn we’ve recently experienced is directly related to this dynamic. In 2008, oil rose to $147/barrel, precipitating a global recession, and we’re still reeling from it.

There are now 98 oil producing nations in the world—and at least 64 of them have already reached their peak in oil production and are in decline. That is fundamentally why oil prices have been rising so dramatically.

Yes, it’s true that there is a bit more oil to be discovered and developed and produced in various parts of the world. But oil discoveries peaked globally around 1960, and have fallen off dramatically despite plenty of investment in exploration. We’ve already picked all the low-hanging fruit, the easy inexpensive oil. From here on in, oil is going to be increasingly expensive and harder to get out of the ground. All the cheap oil has already been burned.

And in a way, this is a very good thing. Because if we had unlimited quantities of cheap oil to burn, and continued doing so, we would quickly overwhelm the atmosphere with carbon to the point that it would be very difficult to grow anything anywhere. Climate change at that level would be devastating to all life on this planet.

Peak oil is an enormous predicament. Our ability to grow food to feed our population has been based on cheap fossil fuels. In fact, our entire global economy is based on cheap fossil fuels. And now we’re bumping into a very fundamental resource limitation that will force us to change how we do almost everything. Worse, though most economists don’t want to consider this yet, peak oil signals the end of economic growth. We are learning that economic growth as we have known it is profoundly unsustainable.

The implications for food and agriculture are staggering, and they are urgent. Last year, the Soil Association in the UK published a key paper, “Food Futures: Strategies for resilient food and farming.” In that document, they say:

“Over the next 20 years we must make fundamental changes to the way we farm, process, distribute, prepare and eat our food. Global food shortages will be inevitable unless we act now to change our food and farming systems.”

One of the key researchers in this area is Richard Heinberg, Senior Fellow at Post Carbon Institute, author of a number of important books that have helped us understand our predicament. Last year, he co-authored a very important paper, which I highly recommend to you, “The Food & Farming Transition: Toward a Post Carbon Food System.” Here he maps the pathways to a much-needed revolution in agriculture.

One of the key researchers in this area is Richard Heinberg, Senior Fellow at Post Carbon Institute, author of a number of important books that have helped us understand our predicament. Last year, he co-authored a very important paper, which I highly recommend to you, “The Food & Farming Transition: Toward a Post Carbon Food System.” Here he maps the pathways to a much-needed revolution in agriculture.Richard is one of the most grounded and most incisive researchers and communicators in the world regarding these issues. I’ve come to deeply trust his perspective and his insights. In a paper titled, “What Will We Eat When the Oil Runs Out?,” Richard says,

“To get to the heart of the crisis, we need a more fundamental reform of agriculture than anything we have seen in many decades. In essence, we need an agriculture that does not require fossil fuels…”A non-fossil-fuel agricultural system! Well, the situation we’re facing does mandate radical changes. Heinberg continues:

“The transition to a fossil-fuel-free food system does not constitute a distant utopian proposal. It is an unavoidable, immediate, and immense challenge that will call for unprecedented levels of creativity at all levels of society.”

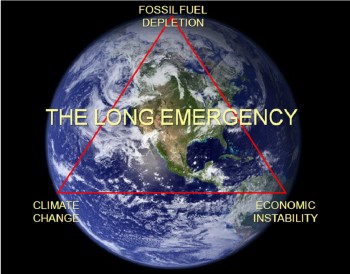

This is all part of a convergence of global crises—fossil fuel depletion, climate change, and economic turmoil—which James Howard Kunstler has called “The Long Emergency.” We need to understand that The Long Emergency is not a problem that can be solved. It is a predicament, a long-term consequence of our own actions to which we must now adapt.

This is all part of a convergence of global crises—fossil fuel depletion, climate change, and economic turmoil—which James Howard Kunstler has called “The Long Emergency.” We need to understand that The Long Emergency is not a problem that can be solved. It is a predicament, a long-term consequence of our own actions to which we must now adapt.Now, at first this might all sound like a disaster. But it doesn’t have to be. It might turn out to be the best thing that’s ever happened to food and agriculture.

Albert Bates, author of The Post Petroleum Survival Guide and Cookbook, says

“The Long Emergency is an opportunity to pause, to think through our present course, and to adjust to a saner path for the future. We had best face facts: we really have no choice. The Long Emergency is a horrible predicament. It is also a wonderful opportunity to do a lot better. Let’s not squander this moment.”As Rob Hopkins, the founder of the Transition movement, says:

“Inherent within the challenges of peak oil and climate change is an extraordinary opportunity to reinvent, rethink and rebuild the world around us.”

In the face of all this, one of the most important things we can do—and must do—is to completely rebuild our local foodsheds—from multiplying backyard and frontyard gardens, to converting our local agricultural lands to growing food for local consumption, to rebuilding local food storage and distribution systems, to training people to learn farming as a wise and essential—and sustainable—career choice.

In the face of all this, one of the most important things we can do—and must do—is to completely rebuild our local foodsheds—from multiplying backyard and frontyard gardens, to converting our local agricultural lands to growing food for local consumption, to rebuilding local food storage and distribution systems, to training people to learn farming as a wise and essential—and sustainable—career choice.Not only will all this help reduce the amount of fossil fuels embedded in today’s food from fertilizer, pesticides and transport, but adopting a more local organic diet will greatly contribute to our health, and our children’s health. It will also reconnect us with those who grow our food, with the land that supports and nurtures us, with the seasons, and with the natural processes and cycles that are fundamental to all life. In the process, we’ll rediscover what community really means. And for most of us, that will be an unexpected and inspiring revelation.

Of course, what I’m pointing to here are qualities of sustainability that can’t be measured, but which we know in our hearts are essential to humanness—qualities and experiences that have been lost to our communities for a long time.

This means that we have no choice but to quickly transition to a world no longer dependent on fossil fuels, a world made up of communities and economies that function within ecological limits. The age of economic growth driven by cheap fossil fuels is over.

And the age of agriculture driven by cheap fossil fuels is over, too.

The Worldwatch Institute recently published its report, 2010 State of the World: Transforming Cultures from Consumerism to Sustainability. In this book, in an article titled “From Agriculture to Permaculture,” Albert Bates and Toby Hemenway (both farmers and teachers of Permaculture) say:

“Humanity now confronts a critical challenge: to develop methods of agriculture that sequester carbon, enhance soil fertility, preserve ecosystem services, use less water, and hold more water in the landscape—all while productively using a steadily compounding supply of human labor. In short, a sustainable agriculture.”Another perspective is from Sharon Astyk, a farmer and mother and writer. In her latest book, A Nation of Farmers: Defeating the Food Crisis on American Soil, she writes:

“Oil has replaced people in industrial agriculture, and now people have to come back and replace the oil.”Sharon calls for a food and farming revolution that is based on simply choosing to change the nature of what we grow and what we eat.

“It is a call for more participation in the food system—100 million new farmers and 200 million new cooks in the U.S., and many more worldwide.”Agriculture is entering into a profound transition, and fundamentally it’s an energy transition that will be unfolding over the next 10 to 15 years—and there probably will be some pretty big bumps along the way. We will have less available energy in the future. And renewables will not be able to come on stream quickly enough or at sufficient scale to avoid fairly drastic changes.

The opportunity we have is to design our descent down this energy curve. Now, the transition to a non-fossil-fuel food system will take some time. Nearly every aspect of the process by which we feed ourselves must be redesigned.

But if we do this right, we have an opportunity to build a food and farming system that is economically viable, environmentally sustainable, resilient and self-reliant, that ensures food security and sovereignty for all, that contributes to the health and happiness of our citizenry, and that revitalizes our communities across the nation.

If we do this right, as Sharon Astyk says:

“Not only can we cease to do the harm that industrial agriculture does, but we can replace it with something better—a better way of growing and preparing food—and also a democracy of the sort that Thomas Jefferson imagined for his nation, a democracy that is not vulnerable to being stolen or sold, as our present one is.”

The Transition Movement

While you’re digesting that, I now want to shift gears for a moment and tell you a little about the Transition movement.

While you’re digesting that, I now want to shift gears for a moment and tell you a little about the Transition movement.In the fall of 2004, in Kinsale, Ireland—the oldest town in that country—Rob Hopkins was teaching the world’s first two-year Permaculture course at a community college there. On the first day of class, he did two things that rocked his world, and his students’, and which led to the birth of an international movement that is focused on designing our way down the energy descent curve.

The first thing Rob did was to show a brand new documentary film to his class, “The End of Suburbia: Oil Depletion and the Collapse of the American Dream.” Has anyone here seen it? The film lays out the coming oil crisis in very compelling terms, and for many it comes as quite a shock at first—as it did for Rob and his students.

The other thing he did was to invite a guest speaker into the class, Colin Campbell, a highly-respected petroleum geologist who happened to live just up the road from the college. Campbell spent decades working for some of the biggest oil companies in the world, and he founded the Association for the Study of Peak Oil (ASPO). Well, Campbell pushed Rob over the edge with his analysis. Here’s a brief sample:

“The second half of the Age of Oil now dawns and will be marked by the decline of oil and all that depends on it, including financial capital. It heralds the collapse of the present financial system, and the related political structures… I am speaking of a second Great Depression.”

As Rob and his students explored the implications of what they had seen and heard, they began considering how vulnerable the town of Kinsale was to the coming energy shocks, and economic shocks, and even food shocks. Rob had the insight that it might be possible to apply the principles and ethics of Permaculture to design a plan for the community to transition off of fossil fuel dependence, learn how to meet its essential needs locally, and in the process become more resilient and self-reliant. Designing such a plan became a very ambitious class project.

As Rob and his students explored the implications of what they had seen and heard, they began considering how vulnerable the town of Kinsale was to the coming energy shocks, and economic shocks, and even food shocks. Rob had the insight that it might be possible to apply the principles and ethics of Permaculture to design a plan for the community to transition off of fossil fuel dependence, learn how to meet its essential needs locally, and in the process become more resilient and self-reliant. Designing such a plan became a very ambitious class project.As they took it on, they envisioned what a truly sustainable Kinsale would look like, set a target of the year 2021, and through a process of backcasting began figuring out what would need to happen each year to get to that goal.

They did an impressive job, and put it into an historical document, the Kinsale Energy Descent Action Plan. In fact, they did such a good job with this that the town council adopted their plan as the plan for the town of Kinsale, and that plan is being implemented there today.

This experience got Rob Hopkins thinking. In fact, it got a lot of us thinking, who were looking at the coming challenges, as we were here in Colorado, watching what was going on in Kinsale. Rob saw that it might just be possible to use the principles and ethics of Permaculture to empower whole communities—even entire cities—to enter into an inspirational community-wide process together to design their own energy descent plans and become resilient and self-reliant.

In 2006, he began prototyping that process in Totnes, England in 2006. And now the Transition process he developed there is being replicated—more or less officially—in more than 280 communities in 16 nations. And informally, there are at least another 2,000 communities who are experimenting with the process. Transition is a bottom-up, grassroots-to-grasstops movement that is rapidly expanding, and generating enormous interest and enthusiasm around the world.

In 2006, he began prototyping that process in Totnes, England in 2006. And now the Transition process he developed there is being replicated—more or less officially—in more than 280 communities in 16 nations. And informally, there are at least another 2,000 communities who are experimenting with the process. Transition is a bottom-up, grassroots-to-grasstops movement that is rapidly expanding, and generating enormous interest and enthusiasm around the world.Hopkins’ book, The Transition Handbook: From Oil Dependence to Local Resilience, published in March 2008, has been a powerful force in galvanizing this movement.

Hopkins says we must quickly make our communities more resilient, less vulnerable to the profound changes that are coming, because we’re learning that resilient communities—“self-reliant for the greatest possible number of their needs—will be infinitely better prepared than those who are dependent on globalized systems for food, energy, transportation, health, and housing.”

The essence of resilience is relocalization, which means moving steadily in the direction of local production of food, energy and goods; local development of currency, government and culture; reducing consumption while improving environmental and social conditions; and developing exemplary communities that can be working models for other communities when the effects of energy decline become more intense.

In May 2008, our organization became the first officially recognized Transition Initiative in the U.S.—and the first in North America, for that matter. By that time, we had already for three years been working towards relocalization in Boulder County.

In May 2008, our organization became the first officially recognized Transition Initiative in the U.S.—and the first in North America, for that matter. By that time, we had already for three years been working towards relocalization in Boulder County.The movement in the U.S. has grown significantly, and as of today there are 58 officially recognized Transition Initiatives in the U.S., five of them here in Colorado.

Meanwhile, we have become a statewide hub to catalyze, inspire, train and support the adoption of the Transition process in communities across the state (some 20 initiatives are already under way in Colorado).

Nearly everywhere that Transition is getting traction, we’re all working on the relocalization of food and farming, the rebuilding of our local food systems, our local foodsheds.

After the Transition Handbook, the first book published by the Transition Network was Local Food: How to Make it Happen in Your Community. It‘s an inspirational and very practical guide for rebuilding a diverse, resilient local food network, drawing on the experience of dozens of Transition initiatives and other community projects around the world.

Rob Hopkins and his co-author set the tone for Local Food early on in the book. They say:

“…By collectively demystifying the contents of the global pantry and by sourcing, growing and producing food independently of centralized, fragile and detrimental food trades, we are rediscovering our own worth as community members—people capable of interacting with and shaping the food landscapes around us… We are bringing our food culture home because we have to. And while we know we can’t move mountains, we are remembering that we can plant seeds.”

Bringing It Home

Let’s bring it back home to the state of Colorado.According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2006 we Coloradans spent nearly $10 billion on food per year—$9.5 billion, $5.4 of which was food to eat at home (we eat out a lot).

97% of food consumed in Colorado is imported from outside the state. Very little of what we consume is organic.

Nearly $2 billion of our 2006 food budget for home consumption was on meat and dairy products, more than a third of the total. (Since that time, our meat consumption has of course increased.)

In Boulder County alone, we spent more than $660 million on food in 2006, almost all of which went outside the local economy.

If we could increase our local food purchases, particularly organic food, this would not only have profound benefits on our health and greatly reduce our contribution to global warming, but would also greatly boost our local economies.

I think we’re severely underestimating the economic power of local organic farming. This is part of what we’re thinking about in relocalizing food and farming.

To be sustaining and sustainable, agriculture must make the transition from an oil-based industrial model to a more labor-intensive, knowledge-intensive, localized, organic model. This means a radical reduction of fossil fuel inputs, accompanied by an increase in labor inputs and a reduction of transport, with production being devoted primarily to local consumption.

A key strategy for building a resilient food and farming system is relocalization. It’s not the only answer, but it’s a powerful step forward. Other strategies include: converting farms to powering with renewable energy; increasing soil fertility through crop rotation, recycling nutrients, natural fertilizers; shifting consumers to local, seasonal diet; switching to diverse multi-enterprise farming systems; adopting organic and biointensive methods of farming; shifting to labor-intensive methods; increasing the number of farmers; seed-saving; rebuilding local processing and distribution systems.

Permaculture and the Transition

As it happens, the entire Transition process of relocalization is based on a deep understanding of a particular form of agriculture—called Permaculture, which you’ve now heard me mention several times.

As it happens, the entire Transition process of relocalization is based on a deep understanding of a particular form of agriculture—called Permaculture, which you’ve now heard me mention several times.So what’s Permaculture? It’s a contraction of two words, permanent and agriculture. It’s really about permanent or sustainable agriculture.

As Wendell Berry says, “A sustainable agriculture is one which depletes neither the people nor the land.”

You could say that Permaculture is the art of making it possible for humans to live in harmony with the Earth, with the biosphere, and with each other.

Essentially, Permaculture is a design approach based on a deep understanding of the principles of how living systems naturally work; it shows us how to design and build (and rebuild) human systems based on those same living systems, and to do that in such a way that sustains human life and the life of the biosphere.

Permaculture shows us how to restore the balance between human life and the biosphere, which as we now know has gotten wildly out of balance.

Permaculture was first developed in the early ‘70s, by Bill Mollison and David Holmgren in Australia, largely in response to the oil crisis of that era, drawing upon indigenous wisdom from all over the world. Now it’s being practiced by farmers small and large, tens of thousands of them, around the globe. And all of those practitioners together have been evolving an enormous body of knowledge and experience that I believe is going to be extremely important to all of us in the coming years.

As many of you may know, when in 1990 Cuba’s supply of oil was cut off almost overnight with the collapse of the Soviet Union, it was the Permaculturists who stepped forward to completely transform that country’s agricultural system to feed its people. They demonstrated how farming could be done on a large scale without fossil fuels and synthetic fertilizers. They converted the nation to an 80% organic, mostly vegetarian diet in 18 months. Urban gardens there now produce 50% of the nation’s produce.

As many of you may know, when in 1990 Cuba’s supply of oil was cut off almost overnight with the collapse of the Soviet Union, it was the Permaculturists who stepped forward to completely transform that country’s agricultural system to feed its people. They demonstrated how farming could be done on a large scale without fossil fuels and synthetic fertilizers. They converted the nation to an 80% organic, mostly vegetarian diet in 18 months. Urban gardens there now produce 50% of the nation’s produce.There’s a powerful documentary film about this, “The Power of Community: How Cuba Survived Peak Oil.” Significantly, to make the rapid transition from fossil-fueled agriculture, Cuba involved 15 – 25% of its population in food production.

When we started our relocalization work in Boulder in 2005, we could only find two people who were teaching Permaculture. Now there are at least 32 Permaculture teachers in the county, who are training scores of new practitioners every year. How many people in this room have taken a Permaculture course? Get to know a Permaculturist!

Designing the Transition (Boulder County Case Study)

In Boulder County, we’ve been asking, “What will it take to build a resilient, sustainable, localized food system? What will replace industrial agriculture?”Here’s some of what we think it’s going to take: more Open Space acreage devoted to crops for food (not fuel or silage); more farms producing food; more biointensive, organic food production; more farmers (a lot more); more CSAs; more/bigger farmers’ markets; more local infrastructure for storage, distribution, and preservation; more local financial resources; more education and training; more backyard and frontyard gardening; more community greenhouses; more commitment by our communities to bring new awareness, energy, and vitality to the local food system, promoting closer connections between members of the community and those who grow our food

In short, we know we need to relocalize our local foodshed, and begin acting as if that local foodshed is just as important as our local watershed.

But how could a grassroots, community-based movement possibly help to accomplish all this?

But how could a grassroots, community-based movement possibly help to accomplish all this?Well, one of the principles of relocalization—and Permaculture—is that you begin in your own back yard. And a lot of people are doing just that. I love the story of Boulder’s Kipp Nash, a city-bound school bus driver who so desperately wanted to be a farmer that he finally began persuading his suburban neighbors to let him plow up their yards to grow vegetables.

I think it’s fair to say that he had no idea what he was getting into. He now has a thriving neighborhood CSA—he calls it an “NSA,” neighborhood supported agriculture—and has been selling produce at the Boulder Farmers Market. He’s a real farmer now, all right—an urban farmer, with all the challenges that rural farmers face. And what he’s doing is contagious. Transition Louisville, for instance, is implementing the same model in their community with a series of “urban farms.”

And hundreds of other people in the area are learning to grow some of their own food, from renting small plots in a community garden, to plowing up their yards and sheet-mulching on an ambitious scale, to raising chickens. Now, we might be slightly amused by all of this, as we witness a whole lot of people suddenly taking up gardening. But there’s something far deeper going on here.

Municipalities such as Longmont and Greeley have had to change local laws recently to accommodate growing public demand to be able to raise chickens. And arcane water laws are being challenged as more and more people are learning that they could greatly reduce their water consumption for backyard and frontyard food production by catching and storing water. “Illegal!?” they say. “It’s what makes the most sense!”

Also, we’ve got the likes of Michael Pollan, Barbara Kingsolver, Joel Salatin, Wes Jackson, Richard Heinberg, Sharon Astyk, and a host of other authors and documentary filmmakers working hard to change the way we all think about food and agriculture, and the way we eat and the way we grow our food.

And we’ve got local people like Ann Cooper who is determined to bring healthy, organic, local food into school cafeterias throughout the Boulder Valley School District, and others who are working to infiltrate other institutions like our hospitals and corporate cafeterias.

And we’ve seen a huge increase in the number of restaurants who are serving truly local food—more than 70 that we’ve identified in Boulder County so far, probably a ten-times increase from 2006. More and more chefs and restaurateurs are building gardens, and some of them are actually investing in farms.

We’ve also seen an enormous increase in the number of CSA subscriptions in Boulder County. Nobody knows the number today, but when we started in 2006 we could identify only about 150 available CSA subscriptions. Now we have individual farms in the county that have more than 300 CSA subscribers, and Grant Family Farms is going for thousands of subscribers. This is a big change! I think we could call that exponential growth.

We’ve also seen an enormous increase in the number of CSA subscriptions in Boulder County. Nobody knows the number today, but when we started in 2006 we could identify only about 150 available CSA subscriptions. Now we have individual farms in the county that have more than 300 CSA subscribers, and Grant Family Farms is going for thousands of subscribers. This is a big change! I think we could call that exponential growth.Meanwhile, farmers markets are growing and multiplying…

A local food system gets built from the ground up, starting at the grassroots level. All of us have something to contribute to this process, and our skills and knowledge and passion are very much needed now—for the current realities are sobering:

Approximately 34,000 people in Boulder County are food insecure (don’t know where next meal will come from). That’s almost 12% of the county population. As energy prices increase and the economy slides, more will join their ranks.

In 2006, our food working group calculated that with the current food and agriculture system, we could feed only about 20,000 people in Boulder County.

Then they looked at the upside. They estimated that with greatly expanded individual and community plots, greatly increased farming for food, bio-intensive methods, reduced calorie intake and simplified diet—basically, doing everything we could think of to increase local food production—this maybe could be increased to ~185,000 people.

But the Boulder County population is 300,000 people. So we know that we’re vulnerable, like most communities. (We heard from a farmer recently that an entire season’s sales at the Boulder Farmers’ Market would only feed Boulder County for half a day!)

EAT LOCAL! Campaign

EAT LOCAL! Campaign

So, at Transition Colorado, right now we’re focusing both on expanding the market for local consumption and rebuilding our local food production capacity in Boulder County. It’s a kind of classic chicken-and-egg challenge, for we certainly can’t have one without the other. So we’re trying to build both at the same time.On the market side, we’ve launched a public education and awareness campaign under the theme of EAT LOCAL!

A key strategy in this is our EAT LOCAL! Resource Guide and Directory, now in its second edition, published just a couple of weeks ago with 10,000 copies being distributed throughout the county. Copies are available here in the back of the room (please take several and share with others).

This is all supported by a rapidly-growing and continually-updated website (www.EatLocalGuide.com).

Through the Guide, and throughout the EAT LOCAL! Campaign, we’re explaining why eating local is so important, and connecting people with all the available sources in the county in a comprehensive directory so they can find what they’re looking for—whether it’s local food producers, or local food supporters. This directory is online, too.

But giving people the reasons and the sources isn’t enough. So we’re helping to provide some incentive, through a 10% Local Food Shift Challenge and Pledge.

But giving people the reasons and the sources isn’t enough. So we’re helping to provide some incentive, through a 10% Local Food Shift Challenge and Pledge.And we’re showing people some of the many things they can do to increase their local food consumption and help support local agriculture.

We’re also helping people learn new skills, because shifting to lower-carbon, mixed-farming organic systems that are less dependent on oil and chemicals will require a lot more people with the right skills working on the land again. So we’ve launched an ambitious Reskilling program—providing instruction in the basic practical life skills we have largely lost, from growing, cooking and canning food, to permaculture design courses. We’ve delivered about 10,000 people hours of Great Reskilling instruction in the last two years.

At the same time, besides driving the market for local food, we’re working to help increase local food production capacity by:

- Getting people to see local organic agriculture as economic development.

- Encouraging people, especially youth, to consider farming as a viable and sustainable career choice.

- Training people in food production, especially Permaculture.

- Helping to organize and support a Boulder County Farmer Cultivation Center.

- Working with the Boulder County Food and Agriculture Policy Council and the Parks and Open Space Department to find ways to convert much of the county’s 17,000 acres of open space ag land to food production for local consumption, and to develop or change policies to support and encourage local agriculture.

- Working with county and municipal governments as they reconsider their comprehensive plans and land use policies, to ensure that local food and agriculture are supported by those plans and policies.

- Working with Slow Money, the massive capital pool being organized by Woody Tasch, an effort to direct local capital into financing local food and farming enterprises.

- Working with local entrepreneurs to exploit new opportunities that are emerging as we seek to rebuild local infrastructure of distribution, storage, processing, and marketing.

- Working with companies like Farmland LP and organizations like Post Carbon Institute, who are developing a far-reaching program of buying conventional farmland and converting it to organic food production as a significant investment opportunity.

- Collaborating with Everybody Eats! and other stakeholders to cultivate a county-wide coalition of governmental and non-governmental agencies, farmers, businesses and individuals to plan and implement a local food and farming system. Call it a local foodshed alliance, if you will.

Conclusion

Clearly, the food and agricultural revolution is already getting underway. Fundamentally, it’s not about simply about lifestyle choices or mere differences in values. It’s arising in response to a growing predicament that is at the heart of our industrial agriculture system and the heart of our globalized economy.This transition is coming whether we like it or not, whether we’re ready or not.

I know there’s a lot of controversy around all this, and a lot of emotions. I suspect a lot of dust is going to get kicked up along the way.

Much of the debate seems to hinge around the goals of sustainability seemingly interfering with farmers’ and industry’s goals of profitability. But sustainable agriculture must of course include economic viability. And that doesn’t necessarily mean “big.”

We sometimes hear “small farming” used as a pejorative term. Small organic farmers often get pigeonholed and tossed aside as a probable relic of the past.

But at the 19th annual Farming for the Future conference in Pennsylvania earlier this month, Bryan Snyder, the Executive Director of the Pennsylvania Association for Sustainable Agriculture said something very significant, and I want to close with his words. He said:

“People like to hear about lots of acres or large numbers of animals and bushels of corn per acre measured in the hundreds. But models of farming that can gross $50,000 to $100,000 on a single acre—or CSA programs that, in some cases and on relatively small acreage, are able to count their customers in the thousands and bank $1 million or more in the spring before even planting a seed—are anything but small!”Snyder’s conclusion is exactly what we have come to at Transition Colorado:

“We must encourage everyone, wherever they are and as a priority, to eat food produced as near to their own homes as possible. Secondly, feed thy neighbor as thyself. From this perspective, local food not only can feed the world, it may be the only way to ever feed the world in a healthy and just manner.”