Complexity theory has been around for a generation now, but most people don’t understand it. I often read or listen to consultants, ‘experts’ and media people who proffer ludicrously simplistic ’solutions’ to complex predicaments. Since it seems most people would prefer things to be simple, these ‘experts’ always seem to have an uncritical audience. Because most of what’s written about complexity theory is dense, academic and/or expensive, I thought I’d try to summarize the key points of complexity theory (focusing on the social/ecological aspects of it, not the mathematical/scientific ones) using lots of examples for clarity, and in a way that might be used practically by those grappling with complex issues and challenges.

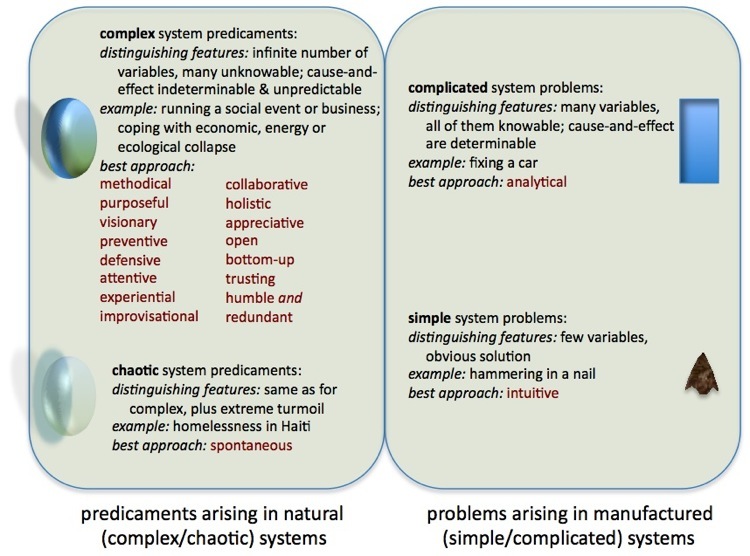

Complexity theory argues that simple, complicated, complex and chaotic systems have fundamentally different properties, and therefore different approaches and processes are needed when dealing with issues and challenges in each of these types of systems.

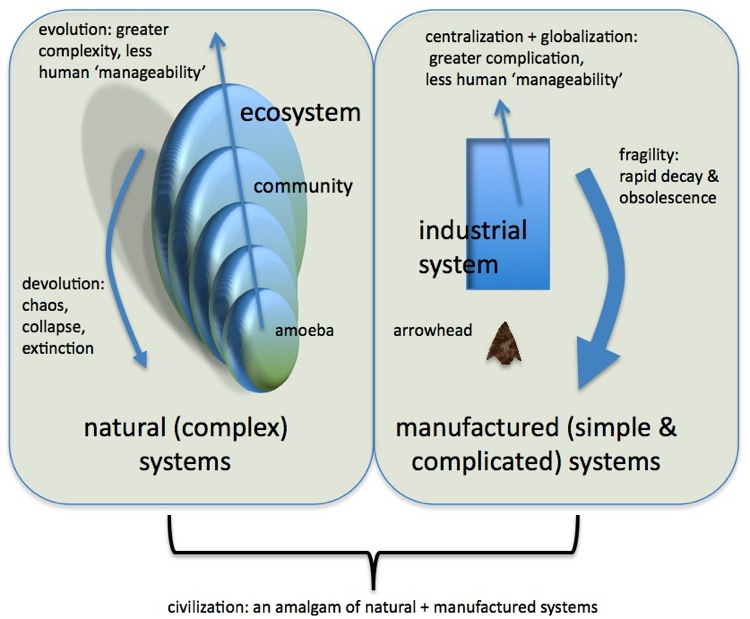

As the diagram above illustrates, natural systems (both social and ecological) are inherently complex. It is the nature of evolution that natural systems, at every level from unicellular life up to our global ecosystem, tend to become more complex and diverse over time, until a crisis (e.g. natural disaster, epidemic, meteor strike) occurs and brings about chaos, system collapse and/or extinction, after which the cycle begins again to evolve towards greater complexity. Even an apparently ’simple’ natural system (like an amoeba) is astonishingly complex, and there is a kind of fractal (or Bohmian hologram) quality to it: all its content is contained in any part of itself, at a lower resolution.

Human invention, for the most part, uses biomimicry, i.e. we attempt to manufacture, to replicate mechanically, things that appear to work in nature. A simple invention like the arrowhead, for example, mimics the speed and penetrating sharpness of predatory birds and animals. Agriculture mimics the natural diversity-diminishing processes of flooding and wildfire. In similar ways, most industrial systems mimic natural systems. But these simple and complicated systems do not evolve of their own accord, they are not self-sustaining, and they lack resilience. They are also fragile, and subject to rapid decay and obsolescence. It takes a huge amount of effort to repair, replace and maintain the components of such systems.

Natural systems are highly effective but inefficient due to their massive redundancy (picture a tree dropping thousands of seeds). By contrast, manufactured systems must be efficient (to be competitive) and usually have almost no redundancy, so they are extremely vulnerable to breakage. For example, many of our modern industrial systems will collapse without a constant and unlimited supply of inexpensive oil.

As natural systems evolve to become more complex, their resilience increases. For example, more biodiversity means less vulnerability to pandemics. However, as manufactured systems become more complicated (e.g. through centralization and globalization) their resilience is reduced. A breakdown in a single component can cause the entire complicated system to seize up or collapse.

The more complex natural systems become, the harder they become for humans to ‘manage’ (control or influence). That is why much of the complex and varied natural world has been replaced by monolithic, homogeneous manufactured systems (e.g. cities, factory farms, dammed waterways), that are much less resilient than the natural, sustainable systems they replaced. Similarly, the more complicated manufactured systems become, the harder they become for humans to ‘manage’. Large organizations (businesses, public organizations and governments) therefore become inherently more and more dysfunctional (and less resilient) the larger they grow.

Our modern civilization is built on amalgams (combinations) of natural and manufactured systems, and it has components that are simple, complicated, complex, or a combination of all three. Almost all businesses, for example, have both social systems (which are complex) and automated systems (which are complicated), and most offer both products (which are mostly complicated) and services (which are mostly complex).

Most of the so-called intractable problems we are now facing (e.g. war, violence, poverty, epidemic disease, and the growing economic, energy and ecological crises) are not ‘problems’ at all, but complex predicaments. The challenges of complex systems are predicaments, not problems, because, since they are not mechanical, they cannot be ‘fixed’ or ’solved’. Alternative, non-mechanistic approaches must be used to deal with them, which is what this article is mainly about.

Simple problems or situations (like hammering in a nail), with few variables (i.e. few things to consider) and which have obvious solutions (strike the nail with the ball of the hammer until it goes in), are best approached intuitively.

Complicated problems or situations (like fixing a car), with many variables, all of them knowable (at least with some study), and where the solutions aren’t obvious but cause-and-effect relationships can be determined, are best approached analytically. Systems diagrams and analytical processes — the type that competent managers and advisors employ — are useful for dealing with complicated situations and problems. Unfortunately, we are all too easily tempted to try to reduce complex predicaments (e.g. how to deal with the nightmarish global debt crisis), to simple or merely complicated problems (e.g. how to get banks to give consumers more credit in the short term so they can spend us out of recession, for now), because we’re good at solving merely complicated problems.

In some complex situations, it is possible to simulate the complexity of the system with a simple or merely complicated model, and achieve useful results, at least in the short term. For example, if you can isolate your organization’s customer service problem to a single cause (say, that service staff don’t have the authority to do the things customers need), you can ’solve’ this problem by giving them more authority. But complex predicaments usually defy such simplification; things are generally the way they are for a good reason, one that’s not obvious or simple (or someone would have ‘fixed’ it already). And people are excellent at finding workarounds for clumsy simple or complicated ’solutions’ that managers or consultants have imposed to try (inevitably unsuccessfully) to ‘fix’ complex challenges. Complicated approaches generally don’t work for complex predicaments, any more than a simple hammer will fix all the complicated problems you might encounter with your car.

Complex predicaments (like running a social event or a business, or coping with economic, energy or ecological collapse) have these four characteristics:

- The number of variables that can have an effect on the system/situation/event is infinite

- Most of these variables are unknown or unknowable; only the most obvious ones can be listed or diagrammed

- The relationships between cause and effect in the system are unfathomable; at best you can notice correlations that may or may not be meaningful

- It is impossible to predict the outcome of an intervention in the system/situation/event (or when Black Swan events and other unforeseeable interventions will occur)

As we come to understand complex predicaments better, we’re learning that the best approaches to them are very different from what works best for simple or complicated problems. Because all the variables cannot be known, and because cause-and-effect relationships cannot be established in complex situations, analytical approaches (like systems flowcharts) used in complicated problem-solving simply won’t work.

The best approaches in complex situations are, well, complex. They entail the use of many different techniques, some of which we are not very good at, and some of which are quite sophisticated, novel, or nuanced. What I have learned so far is that an effective approach to a complex predicament should have these attributes (and I’ll be using the challenge of peak oil and how the Transition movement is working to address it, to illustrate these attributes):

- Methodical: Coping with complex predicaments requires a focus on continuously improving processes, not achieving outcomes. A key feature of complex predicaments is that an appreciation of the true nature of the predicament and an understanding of possible workable approaches to deal with it co-evolve. You can’t know the desired outcome up front, because you just don’t know enough about the situation. Your approach needs to facilitate this co-evolution of understanding, and enable you to go beyond selecting from currently known alternatives and simplistic dichotomies. It also requires an appreciation of the four best ways to intervene effectively in a complex system. In my experience, a methodical approach to any complex predicament requires the skills of an excellent, practiced facilitator, someone with an appreciation of complexity and group process, and the competence to enable the group to do its best work. A good facilitator will:

- Clarify and keep the focus on the group’s purpose and intention (see point 2 below)

- Optimize the use of available space & time

- Help the group manage and enhance its knowledge, learning, and appreciation

- Encourage free flow of creativity & ideas

- Manage the flow of energy in the space

- Help the group deepen and navigate interpersonal relationships

- Help the group appreciate, broaden and shift its perspectives and worldviews

- Model the behaviours the group needs to demonstrate to be effective

- Purposeful: If a group is addressing a complicated problem, the purpose is obvious (to find and implement a solution). When it’s faced with a complex predicament, the purpose is not obvious. The purpose is often itself complex: to deepen an understanding of the predicament, to learn what has worked and not worked in similar situations, to explore options for addressing and coping with it, to imagine how things might be done differently, to identify what the group needs to know and be able to do that it currently does not or cannot, to appreciate the knowledge, ideas, shared values and perspectives of others, to deepen relationships for future collaboration, etc. The group needs to understand and agree on its purpose in all its complexity, and stay focused on that purpose. It also needs to be intentional, i.e. to be willing to and begin to stretch energetically towards achievement of its purpose even as the understanding of that purpose may still be emerging and evolving. For example, a community Transition group’s overarching purpose might be to enable their community to make the transition to a post-carbon economy, and its intention might be to form working groups to focus on various aspects of working towards that purpose. Note that the purpose describes a process not an outcome.

- Visionary: If a group is grappling with a complex predicament, it needs to have a shared vision of what should be different at each step along the process of working towards the purpose, and also a vision of what might happen if they didn’t do that work (often called a “worse- or worst-case scenario”. What would coping with and adapting to the predicament, versus doing nothing, “look like” in the near and more distant future? Several of the Transition communities have developed “timelines” that contain their imaginings of each stage of the transition, possible Black Swan events, and the consequences of inaction. This is how you navigate through complex predicaments, where the outcome is unknown so there’s no clear path from current state to desired future state.

- Preventive: One step in coping with complex predicaments is to try to imagine and anticipate possible negative occurrences as you work towards your purpose, and take steps to head off such occurrences before they happen. An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, as they say. George Monbiot’s Heat, for example, presents a comprehensive climate change prevention strategy, and while many would now argue that we’re too late to prevent catastrophic climate change (and that in any case our society is incapable of moving as fast or as far as Monbiot’s strategy required), the book contains many suggestions for actions that community Transition teams could employ to make the local transition to a post-carbon economy.

- Defensive: When the system is complex, it doesn’t respond to proactive steps (at least, not predictably). It requires some humility and realism to acknowledge that you can’t always control a situation; in complex situations, usually the best you can do is mitigate risks and consequences of what is happening, as you become aware of them, and in the moment, and hence reduce the impact of undesirable situations on you and your community. Ilargi and Stoneleigh’s Automatic Earth for example outlines many steps you can take (such as extinguishing your debts and selling your equities) to mitigate the risks and consequences you will face when the next economic depression hits. A Transition community might likewise mitigate the risks and effects of the end of cheap oil by improving public transport, establishing local renewable energy co-ops, etc.

- Attentive: Complex systems are in constant flux, so it is essential to continually monitor and ‘probe’ to collect information and make sense of what is happening, so that you can respond to unfolding occurrences knowledgeably and effectively. Sometimes the best way to probe what’s going on in a complex system is just to try something, a systematic intervention, and see what happens. Another method is to gather stories and anecdotes and look for meaningful patterns. Sometimes by scanning broadly for data and synthesizing it, you can get a clearer and more actionable picture of the situation. Transition communities across the globe are trying various methods (e.g. car-share and ride-share programs) to see how they effect local dependency on fossil fuels, and collecting and sharing stories, knowledge, ideas and findings with other Transition communities to get a better picture of what works and what doesn’t.

- Experiential: The analytical techniques that are used to address complicated problems are inherently theoretical and hopefully repeatable, and our (left) brains love this “best practices” stuff. Unfortunately, theoretical approaches and “best practices” don’t usually work in complex situations. What works better is experimenting with an array of diverse approaches in parallel and in series, and examining the results and get a collective understanding of what is effective and what isn’t in the real world, and where might be the best place to go from there. The Transition movement doesn’t have a set of “best practices” for coping with the end of cheap oil; what they have instead are “patterns“, synthesized from experiential work, of what approaches seem to be effective across an array of different situations. Two examples of such patterns: Iteration (going through a process iteratively to refine and learn from it is more effective than trying to get it perfect the first time) and Self-Organization (actions seem to work better when the group embracing them organizes itself to plan and implement the actions, rather than having the work assigned to its members by a central control group). More about “pattern languages” in an upcoming post.

- Improvisational: As we have learned from our response to Iraq, Afghanistan, Katrina and other modern crises, preplanning doesn’t work in complex situations. Improvisation entails responding to situations on the fly; for example, emergency workers find improvisational capacity far more useful when dealing with complex crises than procedure manuals, provided these workers are armed with the right tools and knowledge, empowered and connected with others for consultation. Adaptation entails changing yourself or your situation to respond to an outside event, rather than (as we too often try to do, futilely) trying to anticipate, change or control a complex system (the weather, for example). Improvisation and adaptation skills cannot really be learned in a classroom; it takes extensive ‘field’ and/or simulation practice to become competent at them. For example, some Transition community trainers have learned that it’s impossible to know how much their students know, or are ready to know, about peak oil, until the training session is underway, so they often have to improvise their curriculum on the fly. Likewise, some Transition initiatives have run into unexpected obstacles (e.g. bird-lovers objecting to wind turbines), and have had to adapt their programs to suit local sensibilities.

- Collaborative: It’s foolish to believe anyone has all the answers, or can possibly cope alone in this massively interconnected society. Local knowledge, ideas, perspectives and skills are collective assets, and in our atomized, nuclear, specialized civilization, collective understanding and collaboration are the only ways to compensate for the lost core and generalist knowledge and skills that we need to relearn to cope with complex situations. Each member of a group brings a piece of the truth, and unique knowledge and skills, that, especially in dealing with complex situations, are essential to equip the group with collective capacity, competence, understanding, consensus and wisdom. Most of the real work in community Transition initiatives is done through self-organized and self-managed collaborative working groups, that use consensual decision-making processes.

- Holistic: We are usually part of the complex systems whose predicaments we have to cope with. From inside, we get perspective and knowledge of four types: intellectual, emotional, sensory and intuitive. The best approaches are rarely purely rational; it requires synthesizing and balancing all four types of knowledge. Some indigenous peoples say that before making important decisions it is essential to “sleep on it” so that the subconscious knowledge from our hearts, bodies, spirits and DNA can be integrated with our conscious, intellectual knowledge. An essential aspect of the Transition initiative is the “heart and soul” component — appreciating the feelings of grief and anxiety that come along with facing energy, ecological and economic crises. Only when we make space for all four ways of knowing, understanding and responding to predicaments can we bring our full capacity, skill and energy to addressing them.

- Appreciative: There is a tendency for some consultants, managers and experts to presume they know “from experience” how to deal with an organizational challenge, and fail to appreciate the unique context of each situation, or to appreciate that things are the way they are for a reason. It’s essential to understand that reason in all its complexity — how things got the way they are and why they’ve stayed that way — before we can begin to address them effectively. No one is to “blame” for complex predicaments, which often have long and complex histories, and may be self-reinforcing. For example, the Transition movement discovered that trying to reduce the impact of peak oil by improving average gasoline mileage for cars may be ineffective, because as mileage improves drivers may decide to drive farther (for the same price), or drive bigger cars (with the same mpg as the older smaller ones), and hence negate the impact of the regulatory or technological change that enabled the mileage improvement.

- Open: Groups addressing complex predicaments need to be completely honest and transparent, and must be open to different approaches, points of view, directions of inquiry and exploration, and conflicting information. The sponsors and facilitators of such groups must ensure that their invitation is sufficiently open to attract the right, diverse mix of people to address the predicament competently, and that the process they use is open and flexible to the ideas and insights that emerge. Group members can’t afford to “burn bridges” or be closed-minded to even bizarre-sounding scenarios, proposals and knowledge (Einstein said “If at first an idea doesn’t seem crazy, there is no hope for it”.) George Monbiot’s Heat makes some proposals for reducing fossil fuel usage, for example, that some dismissed out of hand, such as converting AC electrical power to DC to reduce power loss, and shutting down all non-essential airplane flights because there is just no way to make such travel energy-efficient. The people who might have moved such ideas forward were just not open to them, and a chastened Monbiot is sounding increasingly pessimistic that his reforms will ever see the light of day.

- Bottom-up: Historically, most solutions have been devised and implemented top-down, by leaders atop political, corporate or social hierarchies. But complex predicaments like poverty, violence, climate change, the debt crisis and resource scarcities have defied all attempts at top-down “fixes”. The best approaches to such issues have come from bottom-up initiatives to deal with them at the local level, at a scale where actions can be taken quickly, and where the people involved know each other and what needs to be and what can be done in their community. This is why the Transition movement is organized as a network, where all the work is done at the community level, and there is no hierarchy.

- Trusting: (This one’s a toughie.) When organizations confront complicated problems, the usual result is a solution (usually imposed top-down) and an allocation of tasks (who will do what by when). By contrast, in confronting complex predicaments, it is essential that team members trust each other to decide what they will individually do, and what they will decide in small groups to collaborate on, and then to do those things. The responsibility rests with each individual — no one can or will stand over them and tell them what to do or how to do it or stay on their case if they haven’t done it. Such implicit trust is foreign to many people experienced with group work, and some believe trust “has to be earned”. What many find difficult in confronting complex predicaments is that they need to just trust people to accept and follow through on their responsibilities, and also that they have to trust a group process that is emergent and pliable, even when that process struggles with lack of consensus, lack of knowledge, lack of ideas, lack of direction, or internal disagreements and conflicts. The Transition movement focuses a lot of attention on trust-building activities, and on ensuring facilitators have the necessary skills to help the group navigate through trust issues.

- Humble: Implicit in the idea that innovation and human ingenuity can ’solve’ any problem is a level of arrogance and hubris that has no place in the struggle with complex predicaments. As I have explained, there is no ’solution’ to complex problems, so what is required is the humility to accept what is, and what cannot be changed, and to adapt. Even now, some technophiles are proposing to ’solve’ climate change by geoengineering — firing trillions of small reflective metal fragments into the atmosphere to deflect much of the sun’s rays. They have absolutely no way of knowing whether this will have the desired effect; this complex predicament has an infinite number of variables, most of them unknowable. Their action, if taken (and it is quite feasible) might backfire, or might plunge us into another ice age — no one knows. Their energies would be better spent learn studying and learning from nature, a humbler pursuit far more likely to come up with sustainable ideas that, at least at the community level, might help reduce energy usage or deforestation or factory farming — three key sources of atmospheric warming. What is impressive about the Transition movement is that their handbooks are not “what to do” guides for dealing with a post-oil economy, but suggested approaches and resource lists for local Transition groups to study and adapt as appropriate to the situation of their community. They’re staying humble, and setting an example for others working to address complex predicaments.

- Redundant: I mentioned earlier that industrial systems strive (out of competitive necessity) for efficiency, and minimize redundancy, which makes them fragile. As we develop approaches to deal with complex predicaments, we need to take the opposite approach: because we can’t know the outcomes of these predicaments, we need to build in redundancy so that we are resilient no matter what happens. Some of the community Transition movements are working to eliminate dependence on fossil fuels entirely, even though there will probably be some hydrocarbons available in the future (e.g. in local coal mines). This gives them a cushion to fall back on in a worst-case scenario, though it probably means they will have a redundant (excess) supply of energy.

Complex indeed! You can appreciate why many people would prefer to recharacterize complex predicaments as simple or complicated problems, and use tried-and-true analytical methods to ’solve’ them — even though the solutions won’t work (though that often isn’t discovered until the consultant, ‘expert’, manager or ‘leader’ has collected their pay and moved on). Fortunately approaches and processes that employ some or all of these attributes are being employed by groups all over the world who have given up on experts and simplistic ’solutions’ and are striving to develop real, working, sustainable strategies to cope with complex predicaments. And an increasing number of facilitators are studying complexity theory and amending their roles and their approaches to this vital work (which is mostly in the public, NGO, and NPO sectors, and mostly unrecognized and under-appreciated), supporting and encouraging the use of complex (emergent) techniques instead of complicated (analytical) ones.

When complex predicaments are left unaddressed for long periods of time, they can sometimes worsen into chaotic predicaments (like the horrific challenge of homelessness in Haiti). Chaotic predicaments have the same characteristics as complex predicaments, with the additional attribute of massive turbulence, to the point that change and crisis are occurring so rapidly or continuously that any type of coordinated, rational response becomes impossible. Any complex system can become a chaotic one during a period of protracted war, hyperinflation, depression, extreme endemic scarcity or other situation where panic or other irrational behaviour prevails. There is no consensus on how best to cope with chaos, or even if an effective approach in such situations is possible; spontaneous approaches, moment to moment, seem to be the main option.

The hopelessness and desperation that often prevails in chaotic situations often produce a power vacuum that can allow charismatic and despotic leaders to take control; the struggling nations of the world are replete with stories of this happening, and there is a danger that, as we in affluent nations face multiple crises in the decades ahead, we too could see the emergence of chaos and fall victim to the false and simplistic promises of fools and tyrants. The best insurance against this, I believe, is to tackle these predicaments while they are complex, using approaches and processes with attributes like the ones I have suggested above, before they become chaotic.