One cannot talk about sustainability for long without eventually encountering “resources.” Every product stream, mechanical process and human action has a source of incoming energy. Our capitalistic market has a couple of favorites that craft the battlements for daily conflicts between corporations and citizens: wood, oil, water, coal. Businesses stuck in narrow focuses of how to utilize and maximize stores of natural resources are fending environmentalists off with a stick and the fight will only get more painful. Sooner or later they will lose. Our country will no longer drill for new oil and the amount of coal we burn each year will progressively decline. What will define the next surge of resource harvesting in the economy over the next century?

Well renewable energy is an easy pick. Wind and solar power will continue to be perfected to peak levels of efficiency and their position in the marketplace will continue to grow, but one of the greatest latent sources of value in our culture is decidedly unnatural. It is available almost anywhere in the country though its particular characteristics vary from one source to the next. Public demand for it is currently a small portion of the greater marketplace but it will only rise over time. The source is our existing buildings. The resulting growth market is deconstruction.

Buildings are piles of embodied energy; resources already mined, cut, erected, assembled, brushed, scrubbed and painted into a finished product, but not necessarily a final product. Whether your currency is carbon, energy, man-hours, water or artistic craft, from homes to office towers each building represents a warehouse of inventory for new projects. These materials also have something that stocks of virgin resources cannot replicate—patina and character from an existing life. Conventional wisdom would dictate that you cannot “build” an antique, but maybe you can.

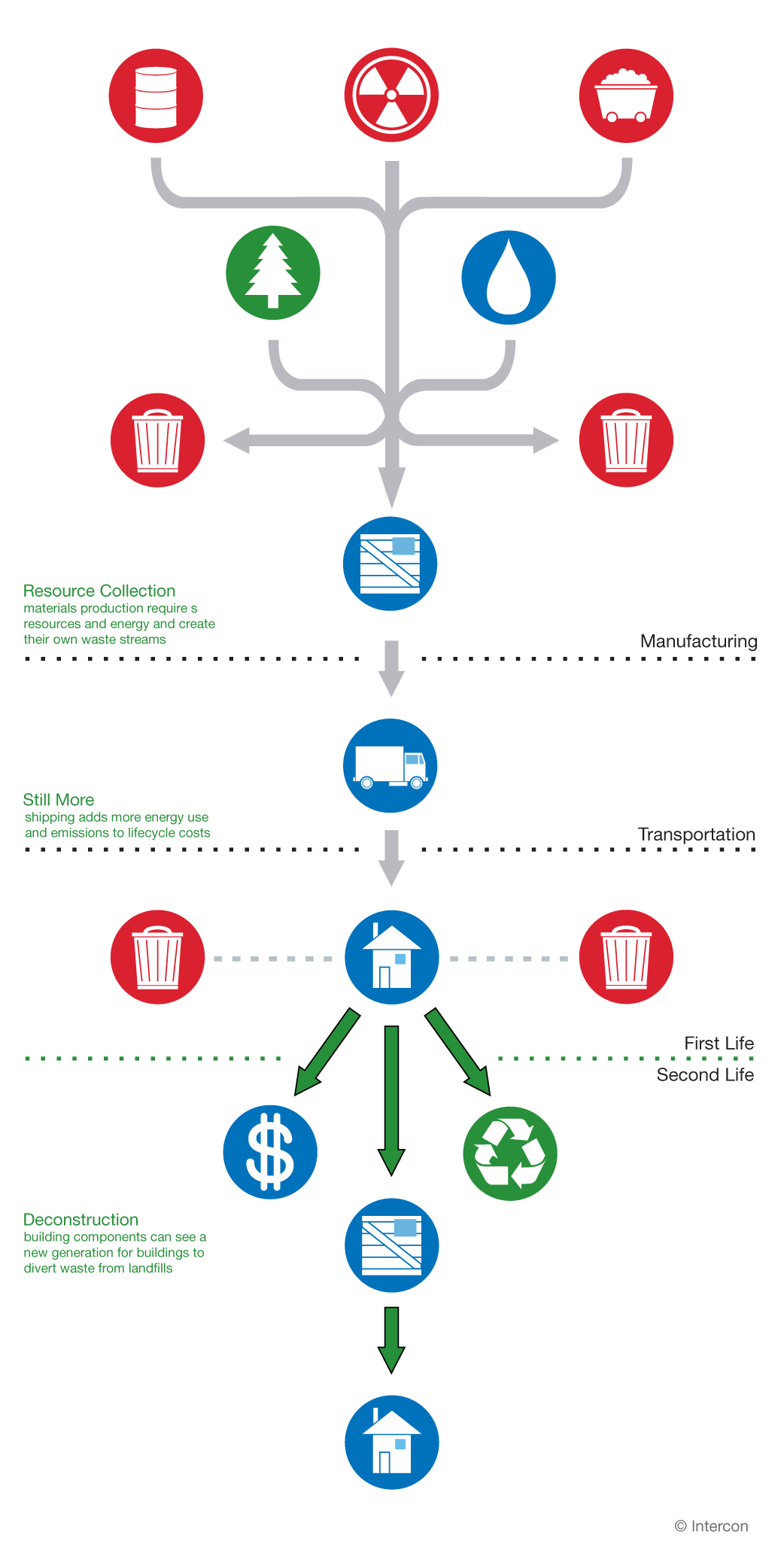

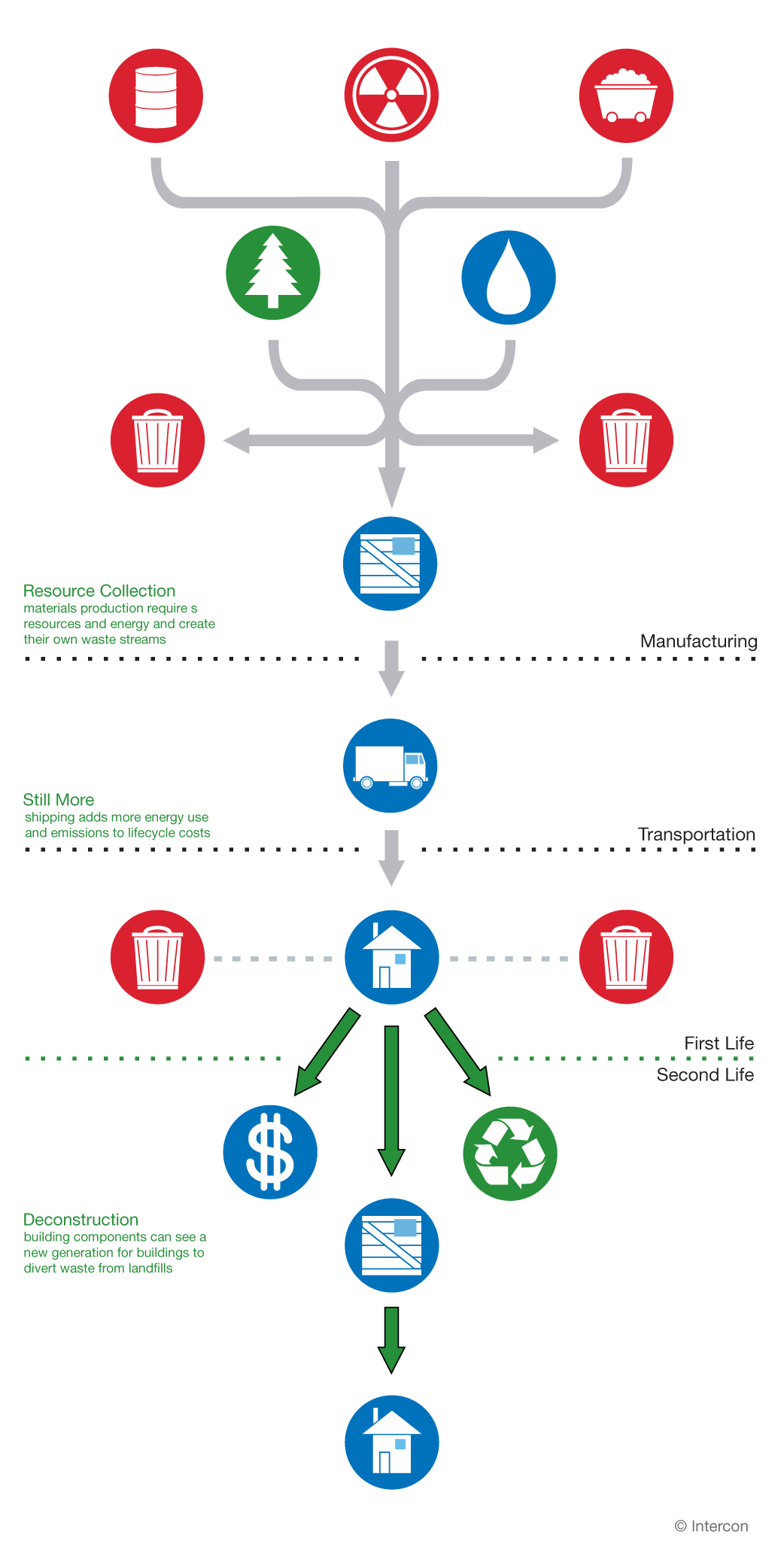

It is true that the most sustainable path is building reuse. Without question it is more efficient to renovate a building than take it apart, but sometimes buildings are beyond repair or new tenants. The Environmental Protection Agency estimated that in 2003 there was 69.6 million tons of demolition waste in the U.S. It would appear we have a lot of stock to work with. What we view as waste is actually a viable production stream for a deconstruction industry that can be resold to new projects. It can take up to 2.64 million BTUs to fire one ton of clay bricks. Imported, dimensioned granite can contain 13.9 mega joules of embodied energy. Utilizing these components means that energy already expended, and its resulting effects on the environment, is not sacrificed into a landfill but molded into a second life with a new use to make its original harvesting more worth while.

There are already some first movers in the deconstruction industry. Companies like TerraMai specialize in deconstruction for reclaiming wood that can be milled and resold for new design projects. A large portion of their stock is found in Asia where hardwoods, used more rarely in the U.S., compose structural framing or railroad ties. With sources like old olive oil casks or Asian teak framing lumber they offer a range of products for a number of applications—all with a touch of time that cannot be manufactured.

So who is buying this stuff? According to TerraMai’s client list a wide array of clients are catching on. Their website boasts store installations of Whole Foods and Urban Outfitters to residences and restaurants that are interested in adding the new level of character to their design palette. The market of buyers may be small now but over time its expansion is imminent.

This budding industry adds value to a waste stream formerly worth nothing, and in doing so, adds value to the existing structures that people already own. What better way is there to restore value into our economy? One of the strongest gripes of greenies is that in the capitalistic model the environment never really gets “valued.” Where on corporate balance sheets is the opportunity cost of old growth forests or clean rivers? Whether it is cobblestones from a courtyard or timbers from a retired barn rising demand for used materials rewards people for keeping and maintaining property.

With the recent recession we have encountered the reality of mortgaged homes falling to a value less than their outstanding debt. The future may offer a similar but more positive reversal: There may be a time when the assessed value of an existing structure is less than the cumulative sale price of its dismantled materials and equipment. Older buildings become cash cows for deconstruction and resale.

Is building with reclaimed materials more expensive? Sure a number of the materials cost a bit more than their virgin counterparts, but the premium is a small price to pay for the authenticity and history engrained within. Upon inspection, the difference is easy to notice. The deconstruction industry offers an opportunity for us to reinvest in ourselves and our prior achievements. Like so many aspects of sustainable ends, education is essential and even architects are only just becoming fully aware of the array of possibilities that reclaimed materials hold. Don’t knock down that barn in he back yard just yet; these days its value may be rising faster than your 401K.from → A Corporate Economy, A Greener Place