Citizens, the ancient Athenians realized, are the best people to identify priorities for action in their own cities. If cities are to become more sustainable, people must take action in the neighborhoods where they live. Most of the urban environmental success stories came about when citizens identified various problems and the links between them in order to pin down cause and effect. A charismatic mayor in Curitiba, for instance, saw that chaotic development and poor public transportation conspired to worsen air pollution: car use increased as buildings sprouted far from bus stops. By winning popular backing for a new bus system, he demonstrated that when citizens understand such connections, they often support or even demand change. -- Molly O’Meara

Most urban residents support strong environmental policies, but wealthy interest groups and corrupt officials often skew local political decisions. -- Molly O’Meara

When citizens have insufficient understanding of the causes of local problems, the political process suffers. -- Molly O’Meara

From every single window in Curitiba, I could see as much green as I could concrete. And green begets green; land values around the new parks have risen sharply, and with them tax revenues. --- Bill McKibben

It is not often we can praise the way our towns and cities are run. They are usually run by people lacking in vision, out for their own self-aggrandizement, mired to their necks in sleaze and corruption.

It is all too easy to find the bad examples. Farnborough, a small town south west of London, the town centre lying derelict thanks to the council pushing through highly unpopular plans to demolish the entire northern half of the town centre for a superstore. The store will face out of the town with its own car park, social housing of 28 maisonettes to be destroyed for the car park. Upton Park in the East End of London, home to West Ham's football ground, where the mayor wishes to destroy the century-old Queen's Market, an undercover street market. 12,000 people who have signed a petition opposing the destruction of Queen's Market, have been dismissed as second class citizens. The mayor is practicing a form of cultural apartheid, ethnic cleansing, wishing to see the poor driven out of the borough and replaced by yuppies occupying expensive apartments.

It is all too easy to find the bad examples. Farnborough, a small town south west of London, the town centre lying derelict thanks to the council pushing through highly unpopular plans to demolish the entire northern half of the town centre for a superstore. The store will face out of the town with its own car park, social housing of 28 maisonettes to be destroyed for the car park. Upton Park in the East End of London, home to West Ham's football ground, where the mayor wishes to destroy the century-old Queen's Market, an undercover street market. 12,000 people who have signed a petition opposing the destruction of Queen's Market, have been dismissed as second class citizens. The mayor is practicing a form of cultural apartheid, ethnic cleansing, wishing to see the poor driven out of the borough and replaced by yuppies occupying expensive apartments.Neither of these examples could be classed as sustainable development. Many more examples could be added to the list.

There are though a few rare exceptions that point in the opposite direction, pointers to the future. Curitiba, a provincial town in Brazil, where sustainable development is not given lip service, but actually practiced, where the people are involved in the planning decisions. Bogotá in Colombia, another example of good urban design, where despite the bad press, crime rate is lower than Washington DC. Porto Alegre, a provincial town in Brazil, is a model of participatory democracy. The local community draw up the budget for the the town, decide how the money will be raised, how it will be spent, then present their findings to the local mayor. Puerto de la Cruz on the northern coast of Tenerife, where the centre of the town is pedestrian streets, tree-lined calles connecting open plazas. Even new developments follow this pattern. And in recent years the car free areas have been extended along the sea front.

The first three examples, two in Brazil, one in Colombia, are all in Latin America. The fourth example in the Canary Islands, has strong Latin influence.

Democracy and happiness: Participatory democracy makes us happier. This is the finding of research comparing Swiss cantons (districts), which differ in the extent to which they use referenda for making major decisions. Most interesting of all, around two-thirds of the well-being effect can be attributed to actual participation itself, and only one third to the improvement in policy as a result of the participation. This was discovered through looking at the well-being of foreigners resident in Switzerland, who get the well-being benefit from the improved decision-making, but not from the participation itself. This implies that an increased ability to participate – both in politics and in the way public services are delivered – may have positive well-being dividends.

In Carfree Cities, the opening chapter develops a yardstick for cities by comparing (car fee) Venice with (car dominated) Los Angeles. You don't even have to read the text, just look at the pictures. In Venice, children, from a very early age, are free to walk the streets, without being under the guard of an adult, and in doing so, learn to interact with the society around them.

Wired News (4 October 2005):

. . . Venice is very much a city of the present and the future. The absence of cars could, in itself, be seen as somewhat futuristic; I'm sure many cities will ban cars from their central areas within the next hundred years, and, like Venice, become places where the loudest sound you hear is the sound of happy human voices. Venice lives by charisma, communication and creativity.What is true of Venice is true of Puerto de la Cruz. Young children are seen walking to and fro school, to and fro the shops, often doing the shopping, they are even found at the local flea market selling off their unwanted possessions. During La Carnaval, they are out in the main square, Plaza Charco, enjoying themselves until the early hours of the morning. Shops and restaurants line the streets, they don't need garish signs to advertise their presence, nor are they part of global chains.

|

For most of his existence, Man has been a hunter-gather, it is only in the last 11,000 years he has been an agriculturalist, and in the second half of the last century, industrial agriculture has appeared.

With agricultural surpluses, cities became possible. The first cities developed were where agriculture began.

The problem with cities is shipping food in and shipping waste out. These two factors have been the limits on the size to which cities can grow.

The Sumerians were among our first agriculturalists, they used water irrigation, had written language, their cities prospered, then collapsed, as did their ancient civilisation.

Their counterparts in the New World, flourished, then collapsed.

The size of modern cities is determined by cheap oil.

The modern city has been with us for a little over a century. The era of cheap oil is about to end. Oil production has peaked, or is about to peak within the next few years. The modern city is unsustainable, assuming it ever was.

Cities have to be designed for people not cars, they have to be closer to Venice in design than Los Angeles.

A measure of the livability of cities, the ratio of parks to car parks.

The car promises mobility, but delivers immobility.

Enrique Peñalosa served as Mayor in Bogotá for three years from 1998. When he took office he did not ask how life could be improved for the 30 percent who owned cars, which seems to be the question asked elsewhere, he wanted to know what could be done for the 70 percent — the majority — who did not own cars.

Peñalosa realized the obvious, that a city that is a pleasant environment for children and the elderly, ie like Venice, would work for everyone. Within just a few years, he transformed the quality of urban life with his vision of a city designed for people.

Under his leadership, the city was transformed, cars were banned from parking on the sidewalks, 1,200 parks were created or transformed, a highly successful bus-based rapid transit system was introduced, hundreds of kilometers of bicycle paths and pedestrian streets were created, rush hour traffic was reduced by 40 percent, 100,000 trees were planted, and local citizens were involved directly in the improvement of their neighborhoods.

The works carried out and the direct involvement of the people created a sense of civic pride among the city’s 8 million residents, making the streets of Bogotá in this strife-torn country safer than those in Washington DC.

Enrique Peñalosa has observed that:

... high quality public pedestrian space in general and parks in particular are evidence of a true democracy at work. ... Parks and public space are also important to a democratic society because they are the only places where people meet as equal ... In a city, parks are as essential to the physical and emotional health of a city as the water supply.The reforms Peñalosa initiated in Bogotá are being carried on by his successor, Antanas Mockus.

Curitiba, a provincial city in southeastern Brazil, has a population similar to Philadelphia or Houston. It faces the problems of all Third World cities, unwanted migration into the city, rural dwellers pushed off the land and lured by the cities. The migrant poor form slums and shanty towns on the edge of the city.

Curitiba, a provincial city in southeastern Brazil, has a population similar to Philadelphia or Houston. It faces the problems of all Third World cities, unwanted migration into the city, rural dwellers pushed off the land and lured by the cities. The migrant poor form slums and shanty towns on the edge of the city.Population 300,000 in 1950, 2.2 million by 1990, and an estimated million more by 2020.

We are used to seeing pedestrian areas in towns and cities, we take them for granted, but in the early 1970s, car-free streets were a novelty.

Curitiba was one of the first cities to have a pedestrian area. This was thanks to Jaime Lerner, a planner by profession, being appointed mayor.

In 1972, the historic boulevard the Rua Quinze de Novembro, was converted virtually overnight, into a pedestrian area. Workman planted tens of thousands of flowers. The street was closed on the Friday night, when it reopened 48 hours later, it was a pedestrian area, one of the first in the world.

Shopkeepers had threatened to sue for loss of trade, by midday Monday, they were petitioning for the surrounding streets to be pedestrianised.

To put what Lerner was doing in context, this was at the time of the construction of Brasilia, the new capital of Brazil, a dazzlingly modern new capital of skyscrapers and wide motorways that was widely seen at the the time as the city of the future.

People took the flowers, workman added more. Protests by motorists, were met by children bearing flowers, which has led to the alternative name of the street Rua das Flores.

Had this historic street not been pedestrianised, it was destined to be destroyed for an overpass, as have so many historic streets in towns and cities across the world.

Cities should not only be designed for people not cars, they should be designed that people do not need cars.

Jaime Lerner turned out to a be a visionary, a rarity in local government, and ultimately served three terms in office, twelve years. His successors have continued his vision.

But successful town design is not top-down, it is organic, it involves the people, it is bottom up.

Richard Rogers was appointed by the British Government to head the Urban Task Force. He was of the view that good design came from the bottom up, through community involvement, but his views fell on deaf ears. The Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott embarked on the Pathfinder project, huge swathes of Victorian houses to be destroyed in the north of England, tens of thousands of houses destroyed. The sustainable option would have been to have renovated the properties and retained existing communities. But no, Prescott in his wisdom, wanted to drive up property prices and provide developers with development opportunities. Great if you are an existing property owner or a developer, but not so good if you cannot afford a home.

Curitiba is not top-down led by the mayor, even though it has been fortunate to have had a visionary mayor. All of the mayors who have followed Jaime Lerner have worked in partnership with private companies, NGOs, neighbourhood and community groups. A series of interactive, interconnected evolving solutions. Wide public debate and discussion, widespread participation, to reach a broad consensus. Most important of all, the best ideas and implementation comes from its citizens.

It is by reaching consensus through wide participation, that solutions can be implemented rapidly and are highly successful.

Curitiba doesn't impose a handful of mega-projects that have been imposed from above, even worse from outside, that its citizens have not been consulted about, let alone want. Instead myriads of little projects, multi-purpose, cost-effective, people-centred, fast, simple, home grown, based on local initiatives and skills.

Curitiba is a success because it involves all its people, treating them, especially the children, not as a burden, a nuisance, a bunch of troublemakers to be ignored or worst still, attacked and victimised, but as its most precious resource, the path to the future.

A classic example of how not to do it is to look at Farnborough in southern England. KPI, a Kuwaiti-funded front-company for St Modwen (a property developer), bought the town centre. They then emptied the town of shoppers and shopkeepers. They imposed their unwanted plans on the town. The local council did nothing to stop them, failed to act in the best interests of the local community, accused members of the local community of being troublemakers, serial objectors, and threatened them with anti-social behaviour orders if they did not desist.

The only opportunity the local community has had to voice their concerns was at a Public Inquiry into highway closures. This was the only occasion the plans were subject to detailed scrutiny, and due to the restricted remit of the inquiry, this was restricted to the road closures, could not look at the plan as a whole.

In Rushmoor (the administrative authority for Aldershot and Farnborough), there is not only a failure to consult, there is a failure to properly notify the local community of planning proposals. When the local community submit their reasoned arguments, there is a refusal to place these submission before the planning committee. Little surprise then that it is known locally as the Rotten Borough of Rushmoor.

St Modwen are now proposing to destroy the century old Queen's Market at Upton Park in the East End of London, with the full blessing of the mayor, the local community dismissed as troublemakers and second-class citizens.

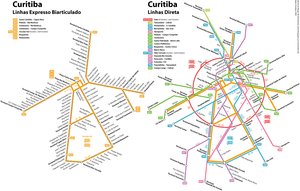

One of the key elements of successful planning in Curitiba is the integrated transport system, especially the bus routes.

Curitiba was the first city to implement rapid bus transit system. Five routes radiate out from the centre of the town. The buses have exclusive routes, running parallel are routes for cars.

RIT-connected

RIT-connected - Express buses: These are large high-capacity buses that have exclusive traffic lanes, spreading radially from the city centre in 5 directions. They are treated as an "above-ground subway" because of their speed, capacity and frequent service. They have bright red color schemes and operate with 'tube stations'. Passengers pay to enter the stations. This allows very quick boarding and disembarking. It is considered shameful to cheat on fares.

- Inter-neighborhood buses: These are green buses that travel outside the city centre. Lines 1 and 2 circle the city centre, the latter with a bigger radius. Lines 3 to 6 are important connections between some neighborhoods.

- Rapid buses: These are silver buses designed to be the quickest links between two points. They cover large distances with few stops. They link with tube stations. Curitiba is the pioneer in the worldwide Rapid Bus development.

- Feeding lines: These are local bus lines and are painted orange. All of them link one passenger terminal to a neighborhood and feed the express buses and other RIT lines with passengers.

- Conventional buses: These yellow-colored buses operate radially from the city centre.

- Interhospitals: These white buses circle the town and link the main city hospitals.

- Tourism line: These colorful buses focus on the city's attractions. Paying around R$10.00 allows one to get on and out of the bus four times, at the attraction of interest. Large windows allow for better sightseeing.

- Around Downtown: These small white buses are designed to circle the city centre, and is used by pedestrians as a quick way of getting to the other side of the area.

At peak times, a bus every minute. The cost in the late 1990s, was the equivalent of 20p for a flat rate fare, and it is not subsidized.

At peak times, a bus every minute. The cost in the late 1990s, was the equivalent of 20p for a flat rate fare, and it is not subsidized. The bus stations link to a 150-kilometer network of bike paths. Although Curitiba has one of the highest car ownerships in Brazil, one car for every three people, people use their cars less than in other towns, two thirds of all trips in the city are made by bus. Car traffic has declined by 30 percent since 1974, even as the population has doubled.

When the bus routes were planned, land zoning also took place, placing higher density near major interchanges and along the radial routes. The city bought up tracts of land to prevent speculators profiting from investment in public assets. The city was able to integrate affordable housing, creating mixed communities, not relegate affordable housing to social ghettos.

During the routing of the fast radial routes, great care was taken to keep destruction of existing buildings to an absolute minimum, routes were adapted wherever possible to existing streets. Compare this to Farnborough, where an estate of 28 maisonettes, social housing set within a grassy, a safe area for children to play, was earmarked to be demolished for a car park for a superstore, the residents of the estate to be forcibly relocated to two blocks of flats surrounded by car parking, the residents encouraged to move by years of disrepair. [see Tragedy of Firgrove Court]

Apart from the damage caused to health by the pollution from cars, people suffer psychological problems if they are deprived of contact with the natural world, an 'asphalt complex'. There is an innate human need for contact with nature, 'biophilia hypothesis'. Deprive people of contact with nature and they suffer a miserable decline in their well-being.

The bus system is publicly-controlled, the buses run by private companies, and entirely self-financing. The money that is paid back to the private bus companies is based on the kilometres of route they cover, not on the number of passengers they carry, which encourages them to provide comprehensive coverage.

The statistics are staggering. The express bus lanes carry 20,000 passengers per hour. The most densely travelled bus system in Brazil. It carries three-quarters of all commuters, 1.9 million passengers per weekday, more than New York.

Curitiba has manage to avoid congestion, the bane of most towns and cities, because people use the buses not their cars. Curitiba enjoys Brazil's lowest rate of car use, leading to cleaner air, saving 7 million gallons of fuel a year, and one-quarter per capita less fuel use than other Brazilian cities.

Lincoln, an ancient city in the east of England with parts dating from the Roman era and the Middle Ages, faces virtual gridlock for most of the day. New roads (lined-with out-of-town shopping), monstrous round-a-bouts, criss-cross the city. When the traffic is moving, you take your life in your hands, whether a car driver, cyclist or pedestrian.

The dire situation was aptly described by Marvin Cottam in a letter to the local paper, the Lincolnshire Echo, headed “Join the 'white knuckle rides' of city road system” (4 April 2006):

Forget Pleasure Island. Forget Fantasy Island. Even forget Alton Towers! If you want spine-chilling, white knuckle ride thrills just take a drive through the city of Lincoln and I'm sure you won't be disappointed!Marvin Cottam goes on to describe the dangers of negotiating the roads in Lincoln, that is when the traffic is moving. Problems that exist only because of poor planning, lack of vision by the city authorities.

Transport in Curitiba is not planned in isolation, it is coupled with land use policy, work schemes, education. A systems approach. A systems approach does not only enhance the environment, it also enhances the social and economic viability of a city.

Molly O’Meara Sheehan:

The stories of Copenhagen, Portland, and Curitiba illustrate how linking transportation and land use can enhance the social and economic vitality of cities. And they offer several important lessons. In many places, however, disconnected transportation investments and land use policies have spurred car-dependent development that has narrowed people’s transportation choices, and created a cascade of harmful effects that were usually unforeseen.

To give people better transportation choices, governments could revise zoning laws to allow homes and stores to be intermixed, and steer new development toward places easily accessible by public transit. They could also provide safe and attractive streets for pedestrians and bicycles, while making sure that connections between cycling, rail, bus, and other forms of transportation, including paratransit, are convenient.

At the time Curitiba started its transportation system, the city began a project called the Faróis de Saber (Lighthouses of Knowledge). These Lighthouses are free educational centers which include libraries, Internet access, and other cultural resources. Job training, social welfare and educational programs are coordinated, and often supply labor to improve the city's amenities or services, as well as education and income. These are strategically placed around the city.

A common theme in the stories of Copenhagen, Portland, and Curitiba is that of people reclaiming streets and making them safer for children to walk and cycle to school. Yet sidewalks and crosswalks, a minimum requirement, are often ignored when government officials are making investment decisions. Lloyd Wright, who works on Latin American transportation projects at the U.S. Agency for International Development, says, “Very often you’re in meetings where municipalities are talking about a $120 million highway interchange, and that goes through without the blink of an eye. But when we talk about a $5,000 pedestrian crossing, it’s like the funds aren’t there.”

Several of the largest of the bus stations, have decentralised city services, to save the local community having to waste time travelling into the city centre to access council services.

Well designed towns and cities work with nature, not against. A city should be seen as a functioning whole, not a sum of its disintegrated parts.

San Luis Obispo, small Californian town north of Los Angeles, restored a creek. The creek is now the main focal point and thoroughfare of the town, with the shops and side streets running off it. You can sit at a restaurant, overlooking the creek.

Curitiba had major problems with flooding, waterways had been canalised, making the problem worse.

Waterways and low-lying land prone to flooding, was turned into parks. People were encouraged to plant trees, residential developments had to have gardens, open space had to be permeable. No-one can cut down a tree without a permit, and if you gain permission, you have to replace it with two trees.

Cove Brook is a small stream that flows through Farnborough (small town southwest of London). It flows from the nearby hills, across Farnborough Airport, then on into the River Blackwater. An area of land was set aside to serve as a flood plain. The local council, in its wisdom, decided the green area could not go to waste and turned it into a golf course. Trees were cut from the surrounding hills, drainage installed on the airfield. When it rains, and the hills become waterlogged, the stream turns into a raging torrent and the golf course turns into a lake. The local council, in its wisdom, has decided it cannot allow the golf course to be rendered unusable for part of the year, and has decided to drain the flood plain, at a cost of £170,000 to the local taxpayer. Housing downstream, already at risk of flooding and which the flood plain was intended to protect, will now be placed at greater risk. Disconnected thinking. [see Council increases risk of flooding]

Cove Brook is a small stream that flows through Farnborough (small town southwest of London). It flows from the nearby hills, across Farnborough Airport, then on into the River Blackwater. An area of land was set aside to serve as a flood plain. The local council, in its wisdom, decided the green area could not go to waste and turned it into a golf course. Trees were cut from the surrounding hills, drainage installed on the airfield. When it rains, and the hills become waterlogged, the stream turns into a raging torrent and the golf course turns into a lake. The local council, in its wisdom, has decided it cannot allow the golf course to be rendered unusable for part of the year, and has decided to drain the flood plain, at a cost of £170,000 to the local taxpayer. Housing downstream, already at risk of flooding and which the flood plain was intended to protect, will now be placed at greater risk. Disconnected thinking. [see Council increases risk of flooding]During heavy rains in Curitiba, the margins of the parks become a little waterlogged and the ducks float a few feet higher.

A sixth of the city is wooded.

Public open space has grown faster than the population. As the population grew by 2.4 times, the public space per person expanded from 5 to 581 square feet per person. 52 square metres of park per capita, higher than New York, higher than any city worldwide, four times higher than the UN recommendations.

In the1970s, the parks created accounted for 10 million square meters of preserved land.

In the 1990s, Curitiba was designated the Ecological Capital of Brazil. Six new parks, the Botanical Garden, and eight wooded areas were created, totaling more than eight million square meters of public preservation areas.

A park created in twenty days, a recycling scheme implemented within months of its inception.

A municipal shepherd and a flock of sheep are employed to mow the grass in the parks. Instead of a cost, the grass becomes a resource, providing meat and wool, which is sold to fund social programmes.

In Curitiba, everything is recycled, even the buildings and the buses!

An old gunpowder magazine converted into a theatre, a foundry into a shopping mall, the old railway station a railway museum, a quarry an ampitheatre, a stunning polycarbonate and cable opera house built in only 60 days.

An old gunpowder magazine converted into a theatre, a foundry into a shopping mall, the old railway station a railway museum, a quarry an ampitheatre, a stunning polycarbonate and cable opera house built in only 60 days. Lincoln, county town of Lincolnshire in Eastern England, has a historic core centred around the Cathedral and Castle, and a less attractive city centre, full of chain stores found elsewhere, typical 'clone town'.

A few minutes walk from the town centre is Brayford Pool, an open basin, once the second most important port in the country after London. Surrounding the pool on two sides were old warehouses, mills and grain stores that survived until the 1960s. These could have been renovated and refurbished, instead all but a couple were destroyed to be replaced by ugly modern buildings. The opportunity to create a pleasant environment, linked to the city centre by a riverside walk, was lost.

In recent years, high rise buildings have been permitted in Lincoln, despoiling the historic skyline. Until then, and since Norman times, the skyline was dominated by the Norman Castle and Cathedral.

In Curitiba, maximum use is made of existing buildings. Schools are re-used in the evening for adult education programmes.

Children are encouraged to establish community gardens to grow food. They are helped by what would otherwise be out-of-work peasants.

The Botanical Garden, Jardim Botânico de Curitiba, was an old garbage dump. The Free University of the Environment was built of old tires and utility poles in an old quarry. It provides education on the environment and land use to everyone, taxi drivers (mandatory), shopkeepers, teachers, journalists, and how it relates to their work.

This is an important aspect of Curitiba, education on environmental issues, easy access to information, to enable citizens to make informed decisions on city plans, and to participate in the planning process.

The average life of buses in Curitiba is 3.5 years (cf average in Brazil of eight years and legal limit of ten). But they then have other uses, mobile information points, job training centres (Linha do Oficio, the Jobs Route or Line to Work), clinics, soup kitchens, food markets, coaches for weekend excursions.

The reused buses are also integrated with a food for waste programme. Unmade roads makes it impossible for lorries to go into the squatter areas to collect garbage. The children are encouraged to bring out the garbage, for which they receive tokens to be exchanged for education and fresh seasonal food. This prevents malnutrition, and keeps farmers on the land who grow the food.

The book of tokens has written on its front cover:

You are responsible for this programme. Keep on cooperating and you will get a cleaner Curitiba, cleaner and more human. You are an example to Brazil and even the rest of the world.One of the major problems facing cities is waste disposal. With the closure of the Fresh Kills landfill site, New York is now trucking waste hundreds of miles to remote landfill sites in Michigan, Pennsylvania and Virginia. New York produces 12,000 tons of garbage every day.

The 1989 initiative, Garbage That Isn't Garbage, saw waste as having value, and led to 70% of households sorting out their recyclable waste for a thrice-weekly kerbside collection. Two-thirds of the bagged and separated waste are recovered and sold, offsetting the cost of collection and disposal, which had been the largest item in the municipal budget. Landfill has been reduced by one-sixth in weight, even more by volume. Recycling of paper saves 1,200 trees a day.

Compare this with Hampshire in southern England, where the council is complimenting itself on having a target to recycle or compost 50% of domestic waste by 2010, the Borough of Rushmoor (Aldershot and Farnborough, towns within Hampshire), where recycled waste is only collected once a fortnight and to cut costs, the council is proposing cutting the collection of other domestic waste from a weekly collection to fortnightly. [see Recycle for Hampshire]

Both Aldershot and Farnborough, have all the indicators of failing towns – disaffected youths hanging on street corners looking for trouble, boarded-up and run down shops, junk food outlets, charity shops, and little else – typical 'ghost towns'.

In Curitiba, council officials are employed to solve problems, not fob the public off with excuses.

Curitiba didn't start out with advantages over any other city, it was not wealthier. In 1980, its GDP per capita was only 10% above the average for Brazil. By 1996 it was 65%.

Companies are attracted to Curitiba because of the pleasant environment, lack of congestion, ease of commuting.

The poor in Curitiba are better off because the cost of living is lower and benefits are better targeted.

The success of Curitiba is also a problem, as it is attracting more migrants to the city.

Writer Bill McKibben visited Curitiba and was very impressed by what he saw:

The first time I went there, I had never heard of Curitiba. I had no idea that its bus system was the best on Earth or that a municipal shepherd and his flock of 30 sheep trimmed the grass in its vast parks. It was just a midsize Brazilian city where an airline schedule forced me to spend the night midway through a long South American reporting trip. I reached my hotel, took a nap, and then went out in the early evening for a walk--warily, because I had just come from crime-soaked Rio.

But the street in front of the hotel was cobbled, closed to cars, and strung with lights. It opened onto another such street, which in turn opened into a broad and leafy plaza, with more shop-lined streets stretching off in all directions. Though the night was frosty-Brazil stretches well south of the tropics, and Curitiba is in the mountains-people strolled and shopped, butcher to baker to bookstore. There were almost no cars, but at one of the squares, a steady line of buses rolled off, full, every few seconds. I walked for an hour, and then another. I felt my shoulders, hunched from the tension of Rio (and probably New York as well) straightening. Though I flew out the next day as scheduled, I never forgot the city.

From time to time over the next few years, I would see Curitiba mentioned in planning magazines or come across a short newspaper account of it winning various awards from the United Nations. Its success seemed demographically unlikely. For one thing, it's relatively poor - average per capita (cash) income is about $2,500. Worse, a flood of displaced peasants has tripled its population to a million and a half in the last 25 years. It should resemble a small-scale version of urban nightmares like São Paulo or Mexico City. But I knew from my evening's stroll it wasn't like that, and I wondered why.

Maybe an effort to convince myself that a decay in public life was not inevitable was why I went back to Curitiba to spend some real time, to see if its charms extended beyond the lovely downtown. For a month, my wife and baby and I lived in a small apartment near the city center. Morning after morning I interviewed cops, merchants, urban foresters, civil engineers, novelists, planners; in the afternoons, we pushed the stroller across the town, learning the city's rhythms and habits. And we decided, with great delight, that Curitiba is among the world's great cities.

The success of Curitiba cannot be simply transferred to other cities, although elements of it can. Los Angeles (of all places) is considering implementing a Rapid Bus System, Beijing has already implemented one RBS route and is considering more.

Not for its physical location; there are no beaches, no broad bridge-spanned rivers. Not in terms of culture or glamour; it's a fairly provincial place. But measured for "livability," I have never been any place like it. In a recent survey, 60 percent of New Yorkers wanted to leave their rich and cosmopolitan city; 99 percent of Curitibans told pollsters that they were happy with their town; and 70 percent of the residents of São Paulo said they thought life would be better in Curitiba.

What can be implemented is involving people in the decision-making process, making our cities greener.

Amory Lovins:

For Curitiba has discovered a way to transcend natural capitalism, supplementing its principles and practices with others that start to achieve what we may call human capitalism. Walter Stahel notes that traditional environmental goals – nature protection, public health and safety, resource productivity – can together build a sustainable economy. But, he adds, only by adding ethics, jobs, the translation of sustainability into other cultures – and we should add, citizenship – can we achieve a sustainable society.In Curitiba, the important principle adopted in 1971: to respect the citizen/owner of all public assets and services, both because people deserve respect and because as Lerner insists: 'if people feel respected, they will assume the responsibility to help others.'

We derive well-being from engaging with one another and in meaningful projects. In particular, the personal development aspect of well-being is likely to be linked with engaging actively with life and our communities. These fndings have implications for policy in relation to civil society, active citizenship and public-service delivery.

Research on well-being comes together with work which has been done on social capita to show the profound importance of our communities and relationships to our quality of life. Community engagement not only improves the well-being of those involved but also improves the wellbeing of others. The relationship is positive in both directions: involvement increases well-being and happy people tend to be more involved in their community, and it improves the community. Therefore, interventions in this area should lead to a positive upward spiral.

Designing sustainable cities, sustainable societies, is about closing loops, a network approach. One of the most important loops we have to close is the political system. Top-down systems do not work, where the people, if they are lucky, are reduced to election fodder to keep corrupt elites in power, to provide them with fig-leaf of legitimacy. We have to close the loop and put the citizens in charge of running their cities, as they once did in Athens.

We no longer have a choice, not if we want to make our cities sustainable, places that are desirable to live in.

web

- Curitiba

- Curitiba - Artes e Parques (English)

- Parques de Curitiba - Ecologia, Natureza e Meio Ambiente

- Artes em Curitiba - Guia de Cultura e Arte

- Curitiba - Wikipedia

- IPPUC - Instituto de Pesquisa e Planejamento Urbano de Curitiba

- Carfree Cities

- World Carfree Network

- Curitibia - COP8 MOP3 (English)

- Biotech Indymedia (COP8 MOP3)

- Indymedia Brazil

Curitiba has trebled in size in just 25 years and now has a population of 1.6 million. With careful planning and an eye on the future, however, the authorities have created a city that is an inspiration for city planners everywhere.

CURITIBA, BRAZIL Three decades of thoughtful city planning |

Curitiba's buses carry 50 times more passengers than they did 20 years ago, but people spend only about 10 percent of their yearly income on transport. As a result, despite the second highest per capita car ownership rate in Brazil (one car for every three people), Curitiba's gasoline use per capita is 30 percent below that of eight comparable Brazilian cities. Other results include negligible emissions levels, little congestion, and an extremely pleasant living environment... |

Nonmotorized Transport and Pedestrian FacilitiesThe policy of encouraging high density development along the five structural arteries has helped to divert transport movement from the city center. The low congestion consequently made it easier to promote other means of travel in the city center. Hence, the city created a pedestrian network, covering an area equivalent to nearly fifty blocks, in the downtown area. Although at first local merchants were opposed to the idea, they quickly found the pedestrian zone to be a tremendous economic boost; much more space was available in the area for customers rather than vehicles, the shopping environment was more pleasant, and people had more time to shop when they did not have to drive and park. Bus terminals on the periphery provide frequent access to the area. Furthermore, the Curitiba Public Works Plan for 1992 calls for 150 km of bicycle paths to be built, following river bottom valleys and railway tracks and connecting the city's districts to make the entire city accessible to bicycles. |

Curitiba's infrastructure makes bus travel fast and convenient, effectively creating demand for bus use in the same way that the infrastructure of traditional cities creates demand for private motor vehicles.

Curitiba is a thriving example of how to 'dismantle' a problem before it starts.

For more information on Curitiba,

go to Dismantlement Links.

Curitiba’s Transportation System Lerner’s administration commenced in 1971 by creating Brazil’s first pedestrian network in the center of the city. But, the most significant changes in the transportation system were taken in 1974 with the creation of the road hierarchy and land control system (Rabinovitch and Hoehn, 1995). In coordination with the Master Plan they began to construct the first two out of five arterial structural roads that would eventually form the structural growth corridors and dictate the growth pattern in the city. These structural corridors were composed of a triple road system with the central road having two restricted lanes dedicated to express busses.

|

Solving The Fare Problem

With the evolution of the transportation system there increased a need for an effective mode of payment. Curitiba’s city hall wanted to expedite bus service and recognized that one of the factors that generated delays is the hold-up in the mode of passenger payment. Over the years there have been many forms of payment implemented. A new system to avoid delays was created in which the city eliminated transfer payments and substituted them with transfer tokens made of paper. But after 7 months of implementation, the city discovered major forgery of the paper transfers. The city then tried to install a two-fare payment, separating the express fares from the feeder fares (fares for the outlying buses connecting to those going to the city center). This system was repealed after one and a half-years because it favored the rich who resided closer to the center and paid only one fare over the poorer population who resided on the periphery of the city and would have to pay two passages to arrive in the center.

Realizing the social imbalance imposed by this fare mode, the city dropped the feeder fare and allowed passengers to ride the feeder busses for free. After a while the city received public complaints about the unsanitary conditions on the feeder busses. They became sleeping places for the homeless and bus drivers refused to drive these busses. The city then decided to return to the one fare method and built fences between stops for the express and feeder busses. This method proved to be successful until they became overcrowded. They became unsanitary and were often referred to as “pig stalls.”

In 1980, the city finally developed and constructed transfer terminals that operated like subway stations. The terminals, constructed with telephone accessibility, attracted newsstands and flower shops and became aesthetically attractive and user friendly.

It was also at this time that the city introduced automatic ticketing to the system. This form of payment allowed passengers to purchase metal tokens at terminals, newsstands or shops, or pay with money at the bus terminals. They hoped to increase the speed of transfers and boarding of passengers which would expedite bus circulation. The city believed that under careful planning of transfers, passengers could travel throughout the system for only one fare. Despite the fare issues, the city had to deal with the overwhelming attraction of the express system. Upon its implementation in 1974, its novelty and popularity resulted in overcrowded busses that caused delays in boarding at stops and terminals. To compensate for the loss in time, bus drivers would increase speed, creating potentially dangerous situations and accidents. The city found it necessary to implement speed control monitors, create boarding tubes and tailor bus designs to accommodate the growing demand.

The city also had to create a system in which individual bus companies that catered to the various zones in the city could share revenues without competing with each other. Traditionally the city was partitioned in different zones that were serviced by individual bus companies. But, with the creation of the inter-district routes and the implementation of the Integrated Transportation Network along with the unified fare, passengers could pay one company at a terminal located in a particular zone and ride the system without paying the other bus companies. In 1987 the city addressed this problem by distributing transportation revenue based on the number of kilometers traveled by vehicle type for any given company. With each company given a number of route kilometers and a timetable, each company competes with the schedule not with other companies (Rabinovitch and Hoehn, 1995).

Bus and Station Design

After the construction of terminals and the implementation of the unified fare, the city wanted to develop busses and stations designed with the intention of avoiding fare evaders. For this reason, busses are designed with three doors, two doors for exiting and a front door for boarding. In a category by itself, these urban busses are constructed with turbo engines, lower floor levels, wider doors, and a convenient design for mass transit. Curitiba also developed boarding tube stations that were placed along direct routes and express lanes. To increase convenience, boarding efficiency and reduce fare evaders the tubes elevate passengers to the bus platform level where automatic doors operated by the tube conductor open parallel to the bus doors. Passengers pay an entrance fare at the turnstile and wait for their respective direct or express bus to pass. Disembarking passengers leave the stations through a direct exit.

|

To further assist passengers, each tube station is equipped with station and route maps and with small lifts situated beside the entrance of the tube to help disabled passengers, strollers, and passengers carrying heavy bags enter the tubes with agility.

The Present System of Transportation

The transportation system is made up of three complementary levels of service that include the feeder lines, express lines and inter-district routes. The feeder lines pass through outlying neighborhoods and make the system easily accessible to lower density areas. Sharing the roads with other vehicles, these feeder lines connect with the express system along the structural corridors.

|

|

The feeder routes are characterized by orange conventional busses that connect the terminals with the surrounding neighborhoods.

| speedy |

| padron |

| articulated |

Inter-district routes use green padron or articulated busses that connect transfer Terminals to different districts without passing through the center of the city. The direct speedy routes are silver and use the tube stations along routes that link the main district and surrounding municipalities with Curitiba. Then there are Conventional Integration Radial Routes that are marked by yellow padron busses. They operate on the normal road network between the surrounding municipalities, the integration terminals, and the city center. The City Circle Line is a fleet of white mini-busses that circle the major transport terminals and different points of interest in the downtown area. All school busses are marked with a yellow stripe and busses dedicated for the disabled are blue. The Integrated Transport System is made up of 340 routes that utilize 1,902 busses to transport 1.9 million passengers per day. The entire network covers 1,100km of roads with 60km of it dedicated for bus use. There are 25 transfer terminals within the system and 221 tube stations that all allow for pre-paid boarding. The Integrated System also has 28 routes and special busses dedicated to transporting special education and disabled patrons.

Conclusions

Curitiba’s system of transportation is an example of effective urban planning. The city’s urban planners recognized that even if growth in population cannot be controlled, the development of infrastructure in the city can guide the city’s expansion. By approaching transportation as tool used to attain a greater solution rather than as a solution to an advancing problem, they were able to implement an efficiently constructed, cost-effective transportation system that finances itself. The city used busses because it had a tradition of using busses. While this system is powered by diesel, the reduction of the number of cars used compensates, if not surpasses, the difference in carbon monoxide emissions. Like every city, Curitiba’s transportation system is plagued by overcrowded peak hours and untimely busses. But, this is a relatively minor inconvenience in comparison to the service provided and the proximity served. From personal experience I can testify to the agility of this system. In comparison with transportation systems in Rio de Janiero, where passengers have to flag down and run after a number of private busses that provide service to the same destination using different routes and New York City were busses are often caught in unrelenting city congestion for a good part of the working day, Curitiba's integrative bus system with its express lanes and bus expediency, essentially works.

![[embossed bonsai]](http://www.dismantle.org/IMAGES/curibon2.jpg)