By Neal Gorenflo

It's Time to Go Big: A Vision for the Sharing Economy

The sharing economy is in a regulatory crisis. Airbnb’s hotel tax issues, the cease and desist orders slapped on peer mobility apps Sidecar and Lyft, and other brushes with the law have catalyzed a flurry of organizing and dialogue about sharing economy regulation.

It started with the launch of San Francisco’s Sharing Economy Working Group in April, and was followed with the formation of the Bay Area Sharing Economy Coalition in August, lobbying by the Collaborative Economy Coalition at the Democratic National Convention in September. SPUR’s Gabriel Metcalfe wrote a provocative opinion piece about it earlier this month, and Shareable’s April Rinne and NYU professor Arun Sundararjan offered much commented counterpoints.

This is a sure sign the sharing economy is maturing. It’s big enough for the government to take notice and participants are strong enough to begin working together. Before this space crystallizes further, it’s a good time to reflect on what's possible. The opportunity to shape the direction of this movement may soon pass. Below I reflect on what I see as the biggest opportunity before us - nothing less than a radical democratization of the economy - and how to make it happen.

Lead with vision

Talking about new laws before there’s a vision to pave the way is putting the cart before the horse. Many get this, but it's understandably not the top priority in the face of pressing regulatory issues. Nothing truly transformative has ever been accomplished without an inspiring vision. History provides ample evidence of the power of vision.

Apple’s 1984 Macintosh TV ad is a famous example. The ad didn’t even show the Macintosh computer or mention its features. It delivered a revolutionary message that promised to liberate the creative energies of the oppressed masses. It led with vision.

Dr. Martin Luther King didn’t talk about laws when he delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech. He shared a vision in which America finally lived the meaning of its creed -- that all people are created equal. Dr. King, the Baptist preacher, undoubtedly knew that he must lead with vision, for the bible says in Proverbs 29:18, “Where there is no vision, the people perish.”

President Reagan’s 1984 “Morning in American” election ad evoked a renewed America moving out of late 70s “stagflation.” Reagan’s optimism helped him get re-elected. Reagan led with vision, and his party knows its power. A prominent activist in the conservative movement, Eric Heubeck, advocated for a renewal of a vision-based strategy in a 2001 memo:

We must win the people over culturally – by defining how man ought to act, how he ought to perceive the world around him, and what it means to live the good life. Political arrangements can only be formed after these fundamental questions have been answered.

Offer the vision

As David Bollier and Silke Helfrich put it in a brilliant essay about the rise of a commons-based society, “we are poised between an old world that no longer works and a new one struggling to be born.” Part of that struggle is that there’s no vision for what’s emerging. It’s not just that the old world doesn’t work anymore, it’s also that the old story that gave it meaning isn’t believable and there’s no credible story to replace it. The story of what our society is all about is actually up for grabs. There's no bigger "myth gap," as Story Wars author Jonah Sachs might put it. And there’s arguably no bigger opportunity for change.

The sharing community has two choices. It can ignore this opportunity. It can develop a narrow vision for the sharing economy and offer one among many competing visions. Or, it can develop a vision that shows how the sharing economy addresses the world’s greatest challenges and offers a new, inspiring way forward for society. We have the opportunity to develop the vision, the one that defines “what it means to live the good life.”

Is the sharing economy qualified to be the vision? Yes, I believe so. In fact, I don’t think there’s anything else that can radically reduce poverty and resource consumption at the same time, something humans must do to stabilize our global climate and society.

However, the sharing economy is not only a real solution, it’s also an inspiring true story. People experience it as empowering. It puts people in a new, constructive relation to one another. In the sharing economy, we host, fund, teach, drive, care, guide and cook for friends and strangers alike. This is a world where people help each other. It’s also a world where self-interest and the common good align.

It’s no wonder people experience sharing as empowering. It’s how we raise children. It’s how we celebrate. It’s how we survive disasters. Sharing has played a crucial role in all of humanities greatest accomplishments, from the moon shot to the development of the Internet. Our economy depends on the commons. Business isn’t possible without nature’s bounty, taxpayer-funded infrastructure, and the sense making of culture. Nearly every religion teaches its wisdom. Sharing is bedrock to our well being, but it’s also the path to self-actualization.

Mythologist Joseph Campbell discovered a universal story found in every culture he called the hero’s journey. The hero’s only path to maturity is to leave home, undergo an enlightening ordeal, and bring back a gift to heal society. This dramatizes what we all know about heroes -- that they selflessly serve others. Sharing activates the hero archetype that’s in all of us. That’s why it resonates so deeply. And why we hold the deepest reverence for those that help others the most, from Jesus to Gandhi to Dr. King.

For all these reasons, the sharing community would be foolish not to go big on vision, to redefine what the good life means and how to get it. The epic crises we face call for real solutions. And citizens everywhere are desperate to see a real way out.

The vision must come from many

At Shareable, we cover the sharing economy as a paradigm shift in how we produce, consume, and govern. It includes startups like Airbnb, RelayRides and Loosecubes but is much bigger than them. There’s no question that the bulk of attention is currently going to this part of the sharing economy. As I mentioned, this group is coming together around regulatory concerns.

This is good. They can help each other. However, a vision of the sharing economy must come from a much broader coalition. A vision promoted by a small group of technology entrepreneurs who have billions of dollars in stock options collectively will seem self-serving. As with any message, the credibility of the messenger matters. While it was possible last century, a vision promoted by a narrow and privileged slice of our society can’t become the ordering vision of our day.

In order for that to happen, these companies should, after organizing themselves, help build a broad coalition working for economic democracy. They’d have a much better chance of getting what they want if they helped others get what they want. Such a group could include the coalition that defeated SOPA and PIPA, Code for America, the Freelancers Union, organizations working for progressive intellectual property laws like Public Knowledge, local economy advocates like BALLE, solidarity economy advocates like the New Economics Foundation, innovative nonprofits like The Public Banking Institute and The Participatory Budgeting Project, commons advocates On The Commons, the open education movement, Creative Commons, the National Cooperative Business Association, and more. Ideally, such a coalition would cut across sectors and political ideologies.

The dramatic transformation of the economy that’s needed is not going to happen until a large coalition begins to work together. All of the organizations I mentioned are focused on a small piece of a much larger puzzle that leads to the same thing – a more democratic economy. Unfortunately, the whole is currently less than the sum of the parts. Significant change will never come from such a disconnected group. However, if they came together to share an inspiring vision, they could pave the way for the regulatory reform needed to democratize the economy.

We’re at a critical juncture. Will the sharing community think small and eventually fade into obscurity as trends do, or will we go on an arduous yet fulfilling hero’s journey to heal society?

I’m in it for the journey. How about you?

IT'S TRUE THAT SHARING IS A SIMPLE CONCEPT AND A FUNDAMENTAL PART OF EVERYDAY LIFE. THANKS IN LARGE PART TO THE WEB, IT'S NOW AN INDUSTRY WITH SEEMINGLY UNBOUNDED POTENTIAL.

Technology is connecting individuals to information, other people, and physical things in ever-more efficient and intelligent ways. It’s changing how we consume, socialize, mobilize— ultimately, how we live and function together as a society. In a global economy where the means of production are becoming increasingly decentralized, where access is more practical than ownership, what do the successful businesses of the future need to know?

- What’s changed about our psychology of sharing?

- Is money the only, or even the most valuable, currency anymore?

- How can Web, mobile and real-time technologies continue to fuel sharing?

- What are the opportunity spaces for business owners & future sharing entrepreneurs?

THE NEW DRIVERS OF SHARING

75% of respondents predicted their sharing of physical objects and spaces will increase in the next 5 years.

TECHNOLOGY

-

Online sharing is a good predictor of offline sharing. Every study participant who shared information or media online also shared various things offline — making this group significantly more likely to share in the physical world than people who don’t share digitally.

-

85% of all participants believe that Web and mobile technologies will play a critical role in building large-scale sharing communities for the future.

ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERNS

- More than 3 in 5 participants made the connection between sharing and sustainability, citing “better for the environment” as one benefit of sharing.*

COMMUNITY

- 78% of participants felt their online interactions with people have made them more open to the idea of sharing with strangers, suggesting that the social media revolution has broken down trust barriers.

- Moreover, most participants (78%) had also used a local, peer-to-peer Web platform like Craigslist or Freecycle- where online connectivity facilitates offline sharing and social activities.

GLOBAL RECESSION

- Over the past few years, the tenuous state of the economy has heightened awareness around purchasing decisions, stressing practicality over consumerism. Participants with lower incomes were more likely to engage in sharing behavior currently and to feel positively towards the idea of sharing than did participants with higher incomes. They also tended to feel more comfortable sharing amongst anyone who joins a sharing community.

Note: This study’s data supports the four primary drivers of sharing as originally outlined by Rachel Botsman, co-author of What’s Mine is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption

THE NEW TIMELESS CULTURE OF SHARING

Sharing is a basic part of human life, so perhaps it shouldn’t come as a surprise that older generations were just as likely to share as Millennials. In fact, participants aged 40+ were more likely to feel comfortable sharing with anyone at all who joins a sharing community (with varying levels of community protections in place) and to perceive “making new friends” as a benefit of sharing, whereas Millennials tended to feel comfortable sharing only within smaller networks.* Attitudinally, however, Millennials were more likely to feel positively about the idea of sharing, more open to trying it, and more optimistic about its promise for the future.

*It’s worth acknowledging that Millennials may simply consider a wider network of people to be “friends” or to have more granular understandings of digital privacy controls, thanks to the rise of social networking — so the relative sizes of these two generations’ trusted networks may not differ greatly, even if their labels do.

“IN BOTH DEVELOPED AND DEVELOPING PARTS OF THE WORLD, PEOPLE ARE EXPLORING HOW TO USE GOODS AND SERVICES MORE COLLABORATIVELY, COMBINING PERSONAL AND SOCIETAL VALUE, UNLOCKING OPPORTUNITIES FOR ORGANIZATIONS OF ALL KINDS AND, ULTIMATELY, CREATING NEW WAYS FOR US TO ENJOY LIFE AND LIVE SUSTAINABLY AT THE SAME TIME." —STEVE MUSHKIN, CEO OF LATITUDE

“A LOT OF THESE ARE VERY OLD-MARKET BEHAVIORS, BUT THEY’RE BEING REINVENTED ON A SCALE AND IN WAYS THAT WE’VE NEVER SEEN BEFORE BECAUSE OF TECHNOLOGY. FOR SURE, MILLENNIALS ARE THE FOOTSOLDIERS DRIVING THIS CHANGE BECAUSE IT’S VERY INTUITIVE TO THEM; THEY’VE NEVER KNOWN ANY DIFFERENTLY. BUT I THINK THAT IT ALSO SEEMS NATURAL TO THE OLDER GENERATIONS—THE WAR-TIME GENERATIONS— BECAUSE THEY HAD A VERY STRONG SENSE OF COMMUNITY.” —RACHEL BOTSMAN, CO-AUTHOR OF WHAT’S MINE IS YOURS: THE RISE OF COLLABORATIVE CONSUMPTION

THE NEW STUFF OF SHARING, THE DRIVE OF DIGITAL

- Not surprisingly, 3 out of 4 participants currently share personal or informational content through social networking platforms. Moreover, 70% share digital media, and 68% share physical media like books and DVDs.

- Of those who share information and media online, approximately 2 in 3 participants use other people’s creations licensed under Creative Commons.

THE STATE OF PHYSICAL SHARING

After information and media, the most shared categories are, respectively:

- Living space (58%)

- Work space (57%)

- Food preparation/meal-sharing (57%)

- Household items/appliances (53%)

- Apparel (50%)

- Car-sharers shared across significantly more categories than non-car-sharers (an average of 11 vs. 8 categories, respectively).

WHAT KIND OF STUFF IS SCREAMING TO BE SHARED?

People are most interested in sharing infrequent-use items that have a high barrier to ownership or a high burden of ownership. This is the primary reason that car-sharing has met with such success over recent years. The other part is a larger paradigm shift where people are just beginning to think about “stuff” differently. They’re focusing on the benefits of access over ownership—of practicality over materialism, experiences over possessions.

- Transportation: automobiles, bikes, boats

- Infrequent-Use Items: household items, event equipment, sporting goods

- Physical Spaces: garages, parking spaces, spare rooms

“OPPORTUNITIES THOUGHT IMPRACTICAL BECAUSE OF PERCEIVED TRUST BARRIERS ARE NOW FAIR GAME. THE EXAMPLES OF LENDING CLUB, COUCHSURFING, AND THREDUP SHOW THAT PEOPLE ARE ENGAGING IN INTIMATE TRANSACTIONS WITH STRANGERS DRIVEN BY TECHNOLOGY, NEW NORMS, AND NEED. THIS IS THE TRUST FRONTIER. WE ARE YET TO DISCOVER HOW FAR WE CAN PUSH THIS FRONTIER. THIS IS THE DECADE WHEN WE ANSWER THE QUESTION: "HOW MUCH CAN WE SHARE?" —NEAL GORENFLO, PUBLISHER OF SHAREABLE MAGAZINE

THE NEW OPPORTUNITIES FOR SHARING

The greatest areas of opportunity for new sharing businesses are those where a lot of services do not currently exist within a specific industry category and where a large number of people are currently either a) sharing casually (not through an organized community or service) or b) not sharing at all but would be interested to share. They include transportation, infrequent-use items, and physical spaces.

Three out of every four respondents predicted that their own sharing of physical objects and spaces will increase in the next 5 years.

TRANSPORTATION

- OPPORTUNITY. There’s still a large amount of unfulfilled demand for car-sharing. More than half of all participants either shared vehicles casually or weren’t sharing currently but expressed interest in doing so. For people who share in an organized fashion, cars and bikes were popular for sharing amongst family and close friends but weren’t commonly shared outside this immediate network, relative to other categories of goods.

- CHALLENGE. There’s a significant opportunity for broad-scale transportation sharing if issues relating to member trust, insurance and availability of services (e.g. beyond urban areas) can be overcome.

INFREQUENT-USE ITEMS

- OPPORTUNITY. Many people already share occasional-use household items (such as power tools, kitchen appliances, party supplies, and sporting goods) with friends, but few services exist yet to organize these sharing efforts; 62% of participants either share these items casually now or don’t yet share but expressed interest in doing so, while only 27% currently share through a community or service.

- CHALLENGE. Physical sharing requires a high concentration of local members to offer real value as a service; this can be especially challenging outside dense, urban areas. However, there’s a significant opportunity to share household items in suburban areas if services can generate enough visibility and interest at the hyperlocal level. More than any other categories of goods, sporting/outdoor equipment and household items represent areas where people simply aren’t aware that some services already exist to help them share.

PHYSICAL SPACES

- OPPORTUNITY. People are surprisingly unreserved about sharing the spaces they (or their things) inhabit. Both travel accommodations and storage space ranked among the top 5 categories overall that people who currently share in an organized fashion would share with strangers (given the option to screen other members). Physical space is a valuable commodity, which is why more co-working and peer-to-peer lodging services are popping up and doing well. Moreover, new models of sharing like fractional ownership are refreshing how we think about accessing a variety of different spaces.

- CHALLENGE. Sharing space simply needs to make practical sense in people’s lives in order for them to adopt it; the act must be attached to concrete benefits like saving or making money, more convenient access, or access to otherwise unavailable offerings.

“THE MOST IMPORTANT MOTIVATING FACTOR IN MY DECISION TO CAR-SHARE WAS THE ABSURDITY OF OWNING SOMETHING LARGE AND RELATIVELY EXPENSIVE THAT JUST SITS AROUND. I BENEFITTED BY GETTING GREAT EXERCISE, REDUCING MY CARBON EMISSIONS, AND MAKING SOMETHING AVAILABLE TO SOMEONE WHO REALLY NEEDED IT WHEN I DID NOT.” —FEMALE STUDY PARTICIPANT, 56, ITHACA, NY, USA

“YOU JUST THINK OF THE NUMBER OF CARS ON THE ROAD—THE WHAT THE PEER-TO-PEER MODEL DOES IS IT REALLY ALLOWS US TO OUR OWN FLEET. RESOURCEs THAT WE HAVE IN OUR OWN COMMUNITIES IS SO MASSIVE...LEVERAGE THAT INSTEAD OF STARTING FROM SCRATCH AND BUILDING” —SHELBY CLARK, FOUNDER & CEO OF RELAYRIDES, THE FIRST PEER-TO-PEER CAR-SHARING MARKETPLACE

THE NEW PEER-TO-PEER BENEFITS OF SHARING

Peer-to-peer sharing allows for potentially unbounded scalability, access to more resources and often at closer proximity to us. Because peer-to-peer companies aren’t subject to the overhead cost of purchasing and maintaining a “fleet” of assets all their own, the cost to renters is often lower; moreover, members have the opportunity to monetize their own possessions. These peer-based “marketplaces” help the environment by using the resources we already available more efficiently rather than manufacturing more new goods.

COMMUNITY MATTERS, COMPANY SIZE DOESN’T

Peer-to-peer sharing allows for potentially unbounded scalability, access to more resources and often at closer Most participants liked the idea of sharing services that felt smaller and more proximity to us. Because peer-to-peer companies aren’t accessible, like local or grassroots companies (45%) or venture-funded startups (20%). subject to the overhead cost of purchasing and maintaining a These companies typically foster strong senses of community by virtue of their small “fleet” of assets all their own, the cost to renters is often lower; size, clear communications, and enthusiastic core communities—traits which needn’t moreover, members have the opportunity to monetize their be exclusive to small business. In fact, 22% of participants liked the idea of a sharing own possessions. These peer-based “marketplaces” help the service associated with a major, well-known brand. Point being: regardless of a company’s size, it should focus on earning the trust of it’s community and engaging actively with them.

THE NEW PEER-TO-PEER OPPORTUNITIES FOR SHARING: PRINCIPLES ALL BUSINESSES SHOULD KNOW

THE APPEAL OF PERSONAL MONETIZATION. 69% of all participants expressed that they’d be more interested in sharing their stuff if they could make money from it. Across all industry categories (excepting physical media, apparel, and money), more than half of participants wished to gain access to others’ assets—rather than being a lender or seller who provides access to others, so this money-making draw could be key to scaling up sharing communities.

THE CULTURE OF INDIRECT RECIPROCITY. The most popularly cited barrier to sharing was having concerns about theft or damage to personal property, but 88% of respondents claimed that they treat borrowed possessions well. Reputation is increasingly becoming an important form of currency; communities that offer transparency (such as through open ratings and reviews) encourage good behavior and trust amongst members.

THE REALITY OF SCALABILITY. In the peer-to-peer model, value to members increases as the community grows: more assets are made available, often at closer distances. Scaling up communities shouldn’t be a problem when 53% of all participants are already comfortable sharing amongst people they may or may not know personally (with varying community protections in place).

“THE CONFLUENCE OF MEDIA AND TECHNOLOGY WAS FIRST GROUNDBREAKING IN ITS ABILITY TO CONNECT PEOPLE TO INFORMATION. THEN IT WAS REALLY ABOUT CONNECTING PEOPLE TO OTHER PEOPLE WITH THE ADVENT OF WEB 2.0. NOW THE NATURAL EXTENSION OF ALL THIS IS CONNECTING PEOPLE TO STUFF—TO THE PHYSICAL THINGS OF EVERYDAY LIFE. WE’RE AT A POINT WHERE ONLINE, SHARED INTEREST COMMUNITIES AND ADVANCEMENTS IN MOBILE, REAL-TIME AND LOCATION-AWARE TECHNOLOGIES HAVE CREATED A ‘PERFECT STORM’ FOR SHARING IN THE PHYSICAL WORLD. THERE’S A HUGE OPPORTUNITY FOR BUSINESSES TO CREATE THE TECHNOLOGICAL AND COMMUNITY INFRASTRUCTURE THAT WILL HELP PEOPLE TO SHARE IN NEW WAYS, LOCALLY AND ACROSS MUCH BROADER DISTANCES, THAN WAS EVER POSSIBLE BEFORE.” —KIM GASKINS, DIRECTOR OF CONTENT DEVELOPMENT AT LATITUDE

THE NEW SHARING TAKEAWAYS FOR NON-SHARING BUSINESSES

BECOME A WE-BASED BRAND. The growth of sharing suggests a new climate where, increasingly, people expect that businesses will enable them to improve their own lives and those of others—whether by making more sustainable choices, by providing access to help others meet their own needs, or by spreading the word about a good brand or worthy cause. This dual-benefit model is worthy of further attention by all businesses, insofar as it represents a growing reality for connected culture. Companies can offer value to their communities by acknowledging that money and products are no longer the only—or even the most valuable—element of a brand transaction for many individuals today.

FIND VALUE IN SOCIAL AND ALTERNATIVE CURRENCIES. Sharing culture makes it possible for virtually anything, including specialized skills or knowledge, used goods, and social reach, to become currency. When asked to come up with their own sharing business concepts, many participants envisioned services founded on bartering (non-monetary exchanges) with others in a community. What’s more, there’s a sizable new market for trading time and responsibilities. At present, 61% of participants either share time or responsibilities casually or would be interested in doing so, while only 16% already share through an organized community or service. Forward-thinking companies like Netflix and Threadless have already demonstrated that users can provide value to traditional businesses without buying something: through word-of-mouth, content creation, community innovation, and beyond.

“THE RISE OF SHARING REQUIRES US TO USE A NEW LANGUAGE WHERE ‘ACCESS’ TRUMPS ‘OWNERSHIP’; SOCIAL VALUE BECOMES THE NEW CURRENCY; ‘EXCHANGES’ REPLACE ‘PURCHASES’; AND PEOPLE ARE NO LONGER CONSUMERS BUT INSTEAD USERS, BORROWERS, LENDERS AND CONTRIBUTORS. ALL OF THIS MEANS BUSINESSES MUST REDEFINE THEIR ROLE FROM PROVIDERS OF STUFF TO BECOME PURVEYORS OF SERVICES AND EXPERIENCES.” —NEELA SAKARIA, SVP OF LATITUDE

THE NEW DIMENSIONS OF SHARING

LIFE-CYCLE

- SYNCHRONOUS. A cyclical system of access where members rent or borrow goods, then return them to the central pool for other members to access. Above all, sharing was perceived by participants as borrowing or lending an item for free, seconded by co-owning something with others: essentially, exchanges that involved no monetary gain, as well as synchronous access or collaborative efforts toward a shared goal. Sharing that was asynchronous or which might lead to monetary gain on one end (e.g. renting or buying/selling used items) weren’t as strongly associated with the concept of sharing—but nevertheless chosen as forms of sharing by more than half of respondents.

- ASYNCHRONOUS. A redistribution system where items are passed off—gifted, traded, bartered, or resold— from one owner to the next so that they can be reused.

- COLLABORATIVE. Simultaneous collaboration to achieve a shared goal; involves joining resources like money, time or specialized knowledge.

COMMUNITY DESIGN

- CENTRALIZED. Shareable assets are owned by a single entity which provides access to members; in a centralized model, all members are renters/ borrowers.

- PEER-TO-PEER. Members pool their own assets to share amongst other members. The member collective is comprised of both owners/lenders and renters/borrowers.

CURRENCY

- MONEY (central reserve currency)

- ALTERNATIVE: Knowledge, skills, services, material items, time, reputation & social reach

PARTICIPANTS’ IDEAS FOR NEW SHARING MODELS

KNOWLEDGE (multilateral sharing). “Community college 2.0: provide some sort of structure that lets people let other people know what they know and what they want to learn. If you can get enough people together, everyone is both student and teacher.” —Male study participant, 29, Salt Lake City, UT, USA

SKILLS AND SERVICES (micro-funding). “... a sort of bounty hunting service for open source projects, where people in need would invest into certain features/fixes with (smaller amounts of) money. Bounties would therefore accumulate and developers would profit by providing solutions.” —Male study participant, 24, Ljubljana, Slovenia

MATERIAL ITEMS (multilateral bartering). “... person A needs something that person B has, and person B needs something that person C has, and person C needs something that person A has—except that this service would be free, completely based on bartering.” —Female study participant, 56, Ithaca, NY

COMPOSITE MODEL. “I'll walk your dog while you're away; you water my plants; I'll give you baby toys I don't need anymore; you loan me your lawn mower. I think this kind of interaction is part of community ties and support networks that used to develop naturally and spontaneously and need some encouragement now.” —Female study participant, 38, Providence, RI, USA

THE NEW SHARING ECONOMY METHODOLOGY

Participants from across the globe (n=537) took a Web-based survey which captured sharing attitudes and current engagement with sharing in a variety of contexts, with a focus on establishing benchmarks for the new sharing economy. The study also sought to understand trust, the role of community, and the new psychology of sharing. Participants were asked to ideate future sharing opportunities—new models and service offerings—across industries for both businesses and society at large.

READ THE SERIES! Shareable and Latitude explored study highlights in the following posts:

ADDITIONAL KNOWLEDGE RESOURCES

##

This is a the blog post version of Latitude Research and Shareable Magazine's The New Sharing Economy report available in PDF with charts here.

By Neal Gorenflo

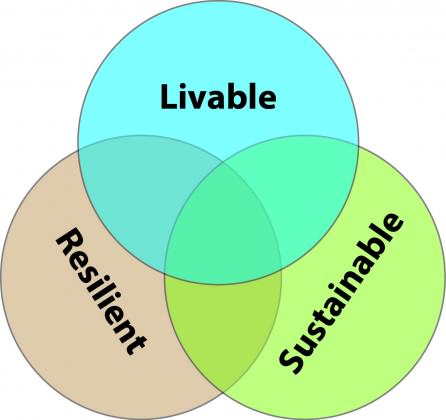

For example, we can imagine sustainable cities—ones that could persist in resource, energy, and ecological balance—that are nevertheless brittle to shocks and major perturbations. That is, they are not resilient. Such cities are not truly sustainable, perhaps, but their lack of sustainability is for reasons beyond our usual definition of sustainability.

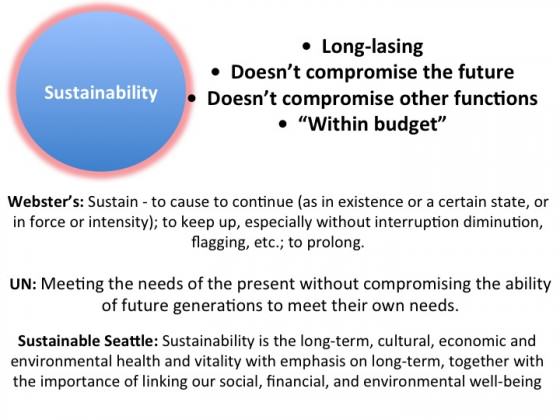

For example, we can imagine sustainable cities—ones that could persist in resource, energy, and ecological balance—that are nevertheless brittle to shocks and major perturbations. That is, they are not resilient. Such cities are not truly sustainable, perhaps, but their lack of sustainability is for reasons beyond our usual definition of sustainability.  Challenge #1: Take the concepts of resilience, sustainability and livability beyond metaphorical status…make them operational by being specific

Challenge #1: Take the concepts of resilience, sustainability and livability beyond metaphorical status…make them operational by being specific

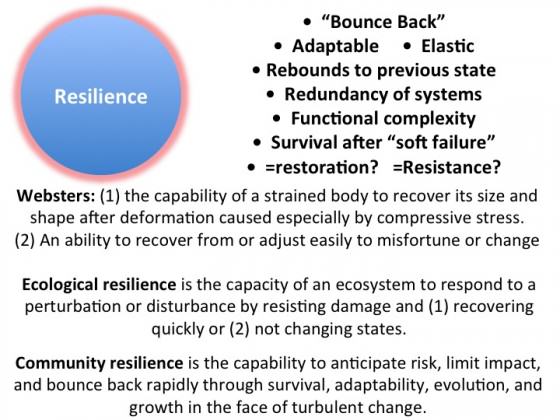

Challenge #2: Acknowledge and confront the differences between resilience, restoration and resistance

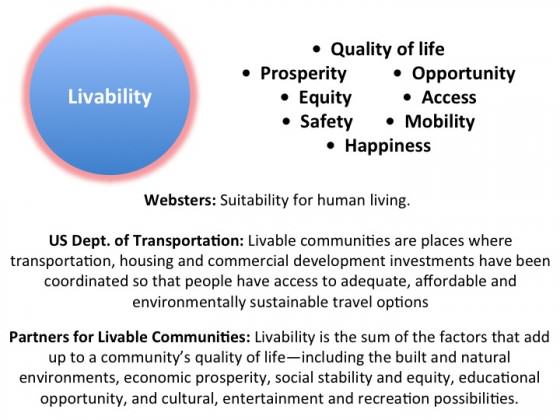

Challenge #2: Acknowledge and confront the differences between resilience, restoration and resistance  The same benefits accrue to other green and blue infrastructure programs that promote resilience, livability, sustainability and social engagement: people get local engaged in projects that benefit them in multiple ways.

The same benefits accrue to other green and blue infrastructure programs that promote resilience, livability, sustainability and social engagement: people get local engaged in projects that benefit them in multiple ways.