Link: https://spiralseed.co.uk/vegan-permaculture-food-futures/

Growing Beyond The Impossible Burger – Towards Vegan Permaculture Food Futures

Growing Beyond The Impossible Burger – Towards Vegan Permaculture Food Futures by Graham Burnett

“Radical agriculture seeks to restore humanity’s sense of community: first, by giving full recognition to the soil as an ecosystem, a biotic community; and second, by viewing agriculture as the activity of a natural human community, a rural society and culture. Indeed, agriculture becomes the practical, day-to-day interface of soil and human communities, the means by which both meet and blend.” – Murray Bookchin, ‘Radical Agriculture’.

Even as a small child in the mid-1960s I seemed to make the connection between the cows I’d see on a Sunday morning during walks in the countryside with my grandad, and the roast beef served up on my plate by my nan an hour or so later. At six or seven years old I was too young to articulate why, but I knew instinctively it wasn’t something I wanted to be a part of. I became vegetarian at the age of 16 in 1977, before finally joining the dots and making the step to veganism in 1984. Around this time I came across a small pamphlet written by then UK Vegan Society secretary Kathleen Jannaway called ‘First Hand First Rate’. This made clear to me the wider connections between animal farming and environmental damage, as well as raising my awareness of the hidden violence behind our food systems;

“Addiction to meat and dairy products and to factory processed food has got such a hold on the minds of people of the dominant Western culture that they find it difficult to question it in their own lives… This wasteful trend must be arrested if the famines of today are not to be repeated on an even more horrifying scale as the population of the world increases.”

Fast forward almost 40 years, and there has been a huge upswing in the availability of plant-based consumer food choices, with veganism now being pretty much mainstream. Of course, this is a good thing. I’m pleased that it’s a lot easier to obtain animal-free convenience foods when eating out or travelling than it was back in the 1980s. It’s great that I can grab a Greggs Vegan Sausage Roll when waiting on a draughty station concourse, and more crucially that conversations and awareness around cruelty-free living and animal liberation continue to open up to an ever wider audience.

Industrial soy production – is it time to move away from the monoculture?

But we also need conversations about how we grow. Going beyond the fact that the fast food chains and supermarkets are increasingly stocked with all manner of processed Impossible Burgers, Chik’n Nuggets and Tofurky, for me the vegan philosophy of compassionate living has always been about more than substituting the products of the slaughterhouse with plant-based (mainly soy, often GMO) ingredients when these are still part of the corporate globalised food production system. Behind the glossy packaging and ‘cruelty-free alternative’ eco-hype the patterns of land exploitation, industrialisation and human alienation from the actual means of production really don’t look so very different as far as I can see. Whether plant or animal based, the current capitalist agricultural model has massive social and environmental impacts and implications. The ‘conventional’ extractive farming methods providing most of the food we consume today are based around the twin goals of maximising output and profit, concerned only with meeting the financial ‘bottom line’ of the big corporations controlling resources and supply lines. Even if we were able to remove the horrors of the slaughterhouse and the factory farm from the equation, that hidden violence hasn’t gone away. Repercussions for human, social and planetary health include;

Deforestation and loss of habitat, with vast areas of land cleared for soy production.

Mass-scale soil degradation in the form of salination, waterlogging, compaction, declining fertility and erosion.

Global water depletion, including the mining of aquifers and ground water sources for irrigation.

Pollution, including nitrification of rivers and oceans caused by artificial fertilisers, and the release of systemic pesticides into the environment

Increasing dependence on external inputs, forcing farmers and growers in the two-thirds world to use genetically modified seeds and hi-tech industrial farming machinery, rather than creating ‘closed loop’ localised growing systems and utilising appropriate technologies.

Decline of genetic diversity through the erosion of food sovereignty and loss of locally distinctive varieties.

Global inequality, poverty and continuing starvation in many parts of the world, as well as the exploitation and dispossession from the land of agricultural workers, in both the ‘west’ and two-thirds world.

Perhaps most significantly in the long term, industrialised agriculture massively contributes to climate change. The global food system, including animal agriculture, is responsible for around half of all greenhouse gas emissions worldwide.

Vegan Permaculture: Cultivating a Harmonious relationship with nature

As the world becomes increasingly aware of the devastating effects of the climate crisis and the depletion of natural resources it’s clearer than ever that we need to find new ways of living in harmony with the earth. It’s time to move away from industrialised monocultural growing systems, and radically reimagine what an eco-vegan agricultural landscape could be like.

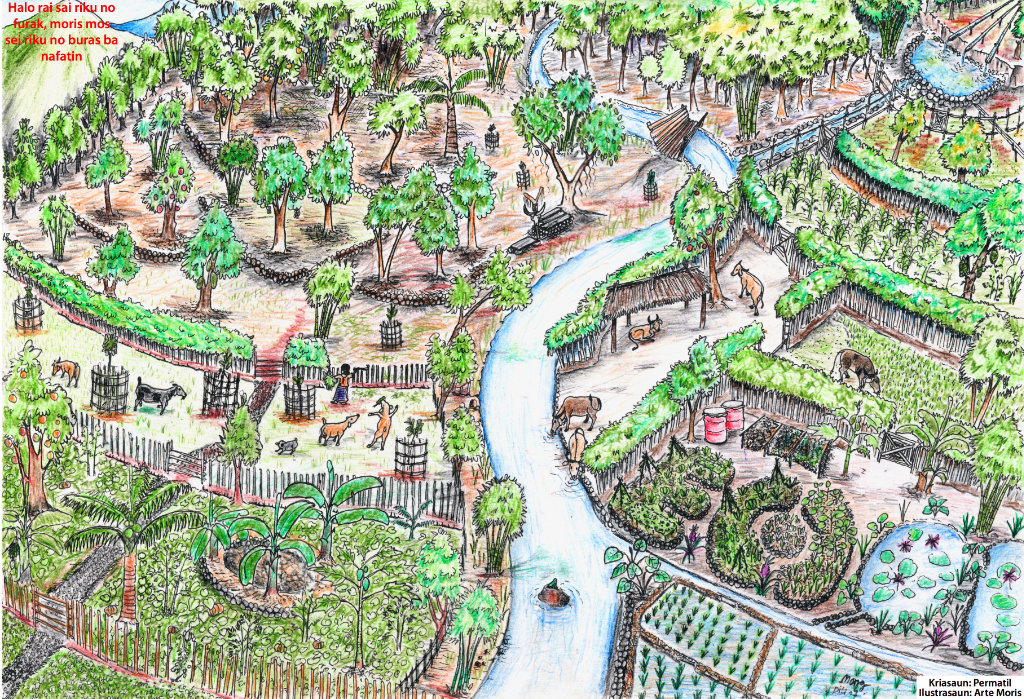

Permaculture is a design philosophy that mimics the relationships and systems found in natural ecologies, emphasising the use of renewable resources, diversity and cooperation to create sustainable communities and ecosystems. Underpinning all permaculture systems are fundamental ethical values around caring for the earth and its peoples, as well as the fair and just distribution of resources. To me these fit well with the vegan philosophy of compassionate living and the precept of ‘do least harm’. In seeking to exclude the use of animal products and cruelty as far as is possible and practicable, a veganic ‘take’ on permaculture asks whether it is enough to simply ‘care for’ our non-human fellow earth-citizens whilst our relationships with them continue to be exploitative, or should we actively promote their recognition as self-willed beings with an intrinsic right to exist free from unnecessary harm?

The Permaculture plot

In traditional permaculture, animals may be used for food, labour, and manure. However, in a vegan permaculture system, these functions are fulfilled through plant-based alternatives, eg, creating polycultures, agroforestry and forest gardening, greater use of perennial crops, and employing techniques such as green manures, vegetal compost mulching and other ways of using organic matter to enrich and rebuild soil health and encourage plant growth.

All of the kingdoms of life thrive in a healthy ecosystem

Yet some ask whether a completely animal-free permaculture system is actually possible. My response is, of course not, and neither would it be desirable. For how would we fence out the earthworms that build our soil and maintain its fertility, or the bees that pollinate our fruit trees and vegetables, and why ever would we wish to? In fact, we actively design in features that are intended to attract wildlife: Ponds for frogs, toads and dragonflies, log piles to provide habitat for slow worms, beetle banks and flowering plants to bring in the ladybirds and hoverflies that keep populations of potential pests like slugs and aphids in check, and are essential to maintaining healthy productive ecosystems. What we don’t include are those animals commodified as ‘system components’ that we believe perpetuate exploitative relationships with our non-human fellow earth citizens, such as pigs, goats and chickens, whose primary function is the production of meat, milk and eggs.

The Symphony of the Soil

So although veganic permaculture aims to create self-sustaining, resilient edible landscapes that are ‘stock free’, in actuality members of several of the Kingdoms of Life (plants, animals, fungi and bacteria) will be working together for mutual benefit. In a forest garden, for example, deep rooted comfrey plants mine nutrients from the subsoil, making them available to fruit trees and bushes. Mammals such as foxes and hedgehogs deposit fertility via their droppings whilst birds and bees buzz around the canopy layer. Meanwhile insects and arthropods patrol the undergrowth and leaf litter, checking and balancing pest populations and playing their role in the cycles of growth and decay. Fungi and bacteria continue the process, breaking down dead matter into rich humus via mycorrhizal networks, all players with their place in the symphony of the soil. Based on the structure of a natural woodland, the forest garden is a complex web of which humans too are an integral part, as we manage, maintain and harvest from these biosystems.

Vegan permaculture is People Care too!

And so vegan permaculture is also about people care, recognising the importance of community and cooperation. By working together, individuals can create sustainable systems that provide for their needs while also protecting the environment. This can take the form of community gardens, co-housing developments, working for social justice, addressing issues around food sovereignty, regenerative economics, ‘green’ transport and other aspects of collective living.

Another World IS Possible: What does veganic permaculture look like in the here and now?

An increasing number of growers and food producers worldwide are adopting the ethics and principles of Vegan Permaculture . Here is just a small sample. An extensive list can be found here.

Woodleaf Farm, Eastern Oregon, USA

Diverse veganic polycultures at Woodleaf Farm, Oregon

Woodleaf Farm is a 211 acre farm managed veganically by Helen Athowe and her family since 2016. 141 acres are maintained as a wildlife sanctuary, and animals are not used for food or manure in the orchards which have 600 peach, pear, apple, apricot, plum, hazelnut, and walnut trees nor in the living mulch vegetable, bean and grain fields. Ecological growing principles utilised at Woodleaf farm include;

Diversifying the soil food web with crop polycultures & ground cover diversity.

Minimising soil disturbance and creating year-round refuges for insect predators, birds, bats, frogs & snakes).

Growing a living root system by feeding the rhizosphere, and recycling nutrients within the plant community, rather than importing mined nutrients, with a focus on slow-release, plant-based Carbon fertilizer amendments.

Farmageddon Growers Collective, Portland, USA

Thriving Farmer’s Market at Farmageddon, Portland, USA

Farmageddon Growers Collective was founded in 2006 by a group of individuals who recognised the need to re-connect with our food system, seeking to grow food in a collective structure that offers a supportive learning and sharing environment using organic and permaculture techniques. They grow around seventy varieties each season including Kale, cabbage, leeks, eggplants, and many other greens. In the words of co-founder Neil Robinson, Farmageddon is about “the spirit of cooperation. Collectivism is about hearing everyone’s voices. We share equipment. We share knowledge. We are learning together. It has been an incredible experience getting connected to the soil.”

Tolhurst Organic, Oxfordshire, UK

Building soils and biodiversity at Tolhurst Organic, Reading, UK

Tolhurst Organic is situated near Reading and consists of 17 acres in two fields and a 500 year old two acre walled garden, and distributes produce via direct sales and a thriving box scheme. It’s been organically managed for over 40 years, and has had no animal inputs for at least two decades. As with the other projects mentioned, Tolhurst utilises a ‘closed systems’ approach, building biodiversity to maintain fertility and naturally managing pest populations by encouraging predators by planting extensive hedgerows as wildlife habitat, using ‘green manures’ as cover crops to avoid any bare soil, and implementing agroforestry systems.

Organiclea workers co-operative, Lea Valley, north east London, UK

Working together at OrganicLea for healthy people, communities and planet

Starting out 25 years ago when a small group of friends took over a couple of abandoned allotment plots in Chingford, in 2010 the project relocated to Hawkwood, a 17 acre former City of London nursery site on the edge of Epping Forest. 24 employed staff and hundreds of volunteers now produce and distribute food and plants locally, and inspire, train and support others to do the same by bringing people together to take action for a more just and sustainable world.

The Challenge and the Vision

“We are faced with the challenge of providing for the needs of a rapidly increasing world population from the diminishing resources of a finite and endangered planet. Fundamental changes in the values and practices of the dominant world system, which has created a situation in which millions of people and animals already suffer extreme deprivation and die prematurely, is essential. What is needed is a trend towards compassionate living the vegan way, with the emphasis on the use of trees and their products. As people face the challenge of environmental crises, as the supreme importance of using awesome intellectual powers with compassion for all sentient beings is realised, an evolutionary leap will be achieved. An era of truly abundant living will dawn in which humans, at peace with themselves, with each other and with all living creatures, will reach heights of creativity as yet unimagined.” – Kathleen Jannaway, Abundant Living in the Coming Age of the Tree, 1991

Sign up to our Vegan Permaculture Design Course, led by Graham Burnett, author of the Vegan Book of Permaculture. Past guest speakers include no-dig expert and writer Steph Hafferty, KMT Freedom Teacher of May Project Gardens in South London, Iain Tolhurst of Tolhurst Organics near Reading, Jenny Hall of Climate Friendly Foods, perennial veg grower Mandy Barber of Incredible Vegetables plant nursery, Joe Kilcoyne and Heather Patrick of Wild Earth Farm and Sanctuary in Kentucky, USA, Paul Payne of Ecoworks community garden in Nottingham and many others. Find out more here

An edited version of this article first appeared in the summer 2023 edition of Growing Green, the magazine of the Vegan Organic Network

Permaculture luminary Rosemary Morrow on the original guidebook:

Permaculture luminary Rosemary Morrow on the original guidebook: